40 Years of National Marine Sanctuaries

In 1872, the United States did something remarkable. We set aside one of our greatest natural treasures, Yellowstone National Park, for future generations to enjoy and appreciate. The logic was simple: this place is truly special, and we have a national responsibility to take care of it.

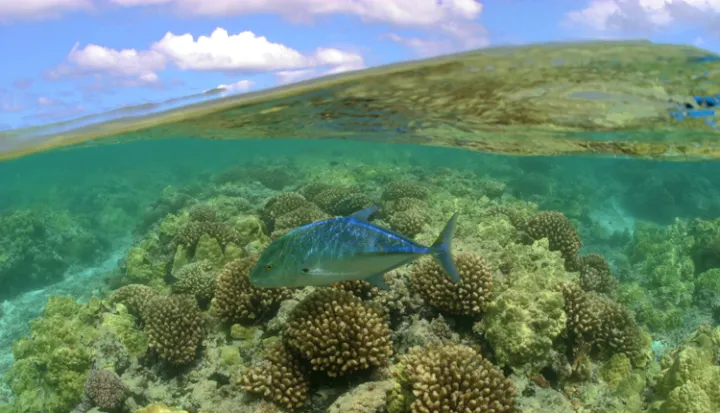

Despite America’s history as a nation inexorably tied to the sea, it would take us another 100 years to accept that the ocean needs the same care and stewardship that we give our national parks on land. Eventually, the warning signs — vanishing coral reefs, declining fisheries, polluted coastlines — became too clear to ignore. “The oceans,” explorer and conservationist Jacques Cousteau declared in 1970, “are in danger of dying.”

Forty years ago on October 23, 1972, amid a flurry of environmental legislation sparked by the conservation movement of the 1960s, President Richard Nixon signed the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act into law. It granted the U.S. Secretary of Commerce unprecedented authority to create “marine sanctuaries” for the preservation or restoration of American waters with special “conservation, recreational, ecological, or esthetic values.”

At long last, the nation had a way to permanently protect the special places beyond our shores, like the colorful coral reefs of the Florida Keys or the vast underwater canyons of Monterey Bay — the Yellowstones and Yosemites of the deep, so to speak. One key question remained, however: where would the first sanctuary be designated?

It started, surprisingly, with a shipwreck. Just a year after the Sanctuaries Act (as it came to be known) was passed, the wreck of the Civil War ironclad warship USS Monitor was discovered off the coast of North Carolina. Resting 16 miles from shore in 230 feet of water, the wreck also fell outside the jurisdiction of any recognized federal authority. Here was arguably the single most significant warship in U.S. history, and no one seemed to know how to protect it.

Meanwhile, North Carolina Congressman Walter B. Jones Sr., saw an opportunity to put the act to use in his home state. While some people suggested creating an entirely new law to protect the ironclad, Jones had another solution: make the Monitor a national marine sanctuary.

Over the last 40 years, NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuary System has grown from one sanctuary to 14 sites of all shapes and sizes, including the nearly 140,000-square-mile Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in the remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Today, the sanctuaries protect a wide range of diverse resources, from fantastic gardens of coral in the Gulf of Mexico to humpback whale breeding grounds in Hawaii. The Marine Sanctuary system even extends to the Great Lakes, where it protects immaculately preserved shipwrecks in Lake Huron.

It hasn’t always been smooth sailing, but the sanctuaries owe their success to their commitment to sound science, education, and community involvement in all aspects of ocean management. With four decades of experience to draw from, NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries will continue to provide lasting protection for our irreplaceable underwater treasures over the next 40 years and beyond.