Aquaculture Comes Full Circle

Until recently we were farmers on land and hunter-gatherers at sea, but how we get our seafood is changing rapidly. With demands for seafood growing and catch from wild fisheries stagnating, aquaculture is an increasingly important player in maintaining seafood as a viable food source around the world. The global aquaculture industry has grown by leaps and bounds since 1980—up 8 percent every year through 2012. In the U.S., roughly half of the fish we eat is farmed, yet almost all of that farmed fish is imported (along with the majority of wild fish).

Farming food from the sea: it sounds like a no-brainer. But it’s not that simple.

Along with the promise of reducing pressure on wild fish and providing more accurate information about the fish we are eating, aquaculture has a host of perceived—and real—problems to overcome. Feed for farmed fish often comes from wild fish, which only adds to the demand. Farmed fish can escape their pens and cages, along with their waste and antibiotics, which could impact wild fish communities and the ecosystems they inhabit.

Enter “integrated multi-trophic aquaculture”, or IMTA. By making use of the waste from one farmed species to grow another (and linking the growth of sometimes even three species together), IMTA provides balance to the aquaculture ecosystem. A project in New Hampshire highlights the possibilities, with fish, shellfish and seaweed being grown all together.

The project is the result of a collaboration between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), New Hampshire Sea Grant, the University of New Hampshire, and the Portsmouth Commercial Fisherman's Association. The fishers hoped aquaculture could maintain their livelihoods in the face of limits to fishing needed to rebuild wild fish populations. Together with scientists at the university, they performed experiments to determine the most efficient aquaculture systems and species for the region. Then fishermen in the community were brought in to test the systems on a larger (pilot) scale. A trifecta of steelhead trout, mussels and sugar kelp was chosen as a test case.

This approach does more than simply provide an alternative to fishing. It also addresses concerns about damage caused by excess nitrogen introduced from fish feed in water, an issue that was raised by the Environmental Protection Agency at a public hearing. By incorporating mussels and kelp—commercially valuable species that can also remove excess nitrogen—fishermen, consumers and the environment can benefit.

Throughout the process, researchers monitored water quality to ensure that the kelp and mussels were doing their ecological “duty” of removing nitrogen from the water. It turns out they were doing that and then some. Since the experiment began in 2011, researchers have found that the kelp and mussels suck up even more nutrients than those that are added through leftover fish food and waste (a.k.a. fish poop).

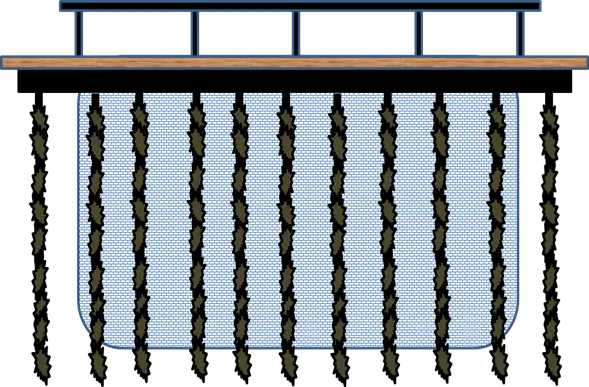

Originally the cage systems were spread out, but the system has evolved to allow for growing all three species together in the same small area of water. The newer, more compact system consists of 20-foot by 16-foot cages that sit in 30 feet of water. The trout are transferred from an inland farm to the cages, which are surrounded by ropes that hang down and hold the growing mussels and kelp (see diagram on the left). A new, robust IMTA system is under development at UNH and will soon be tested in rougher ocean waters.

Other examples of IMTA are being developed along the Norwegian coast, the Bay of Fundy off the eastern coast of the U.S. and Canada, among others. IMTA doesn’t remove from the equation all the possible negative impacts that fish farming can bring to the surrounding environment, such as the spread of disease, antibiotics or sea lice. But its success is a step in the right direction to ensure our wild fisheries remain intact and fish protein continues to feed people around the world. We think this is a cause for #OceanOptimism.