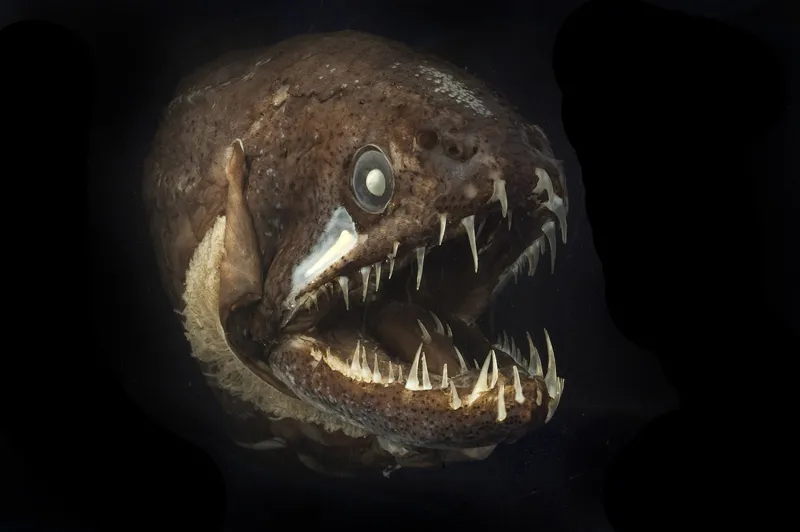

Deep-sea species like this dragonfish (Bathophilus indicus) live in cold, dark waters and may go weeks or months between meals. When food is found, the fish uses its impressive teeth—including some on its tongue—to get a tight grip on its prey.

Census of Marine Life: Wild and Wonderful Creatures

The Census of Marine Life was a ten-year effort by scientists from around the world to answer the age-old question, “What lives in the sea?” The international effort to asses the diversity, distribution, and abundance of marine life that lives in our ocean officially concluded in October 2010. Over the course of looking for organisms in many ocean habitats—coral reefs, the deep sea, the abyssal plain, hydrothermal vents, and others—researchers discovered thousands of new species and photographed many others for the first time. Browse a small sampling of the amazing marine life documented by Census scientists in this photo slideshow. Not enough for you? Check out other slideshows of coral reef species, squids, and deep-sea corals.

Dragonfish from Australia

Credit: Dr. Julian Finn, Museum Victoria

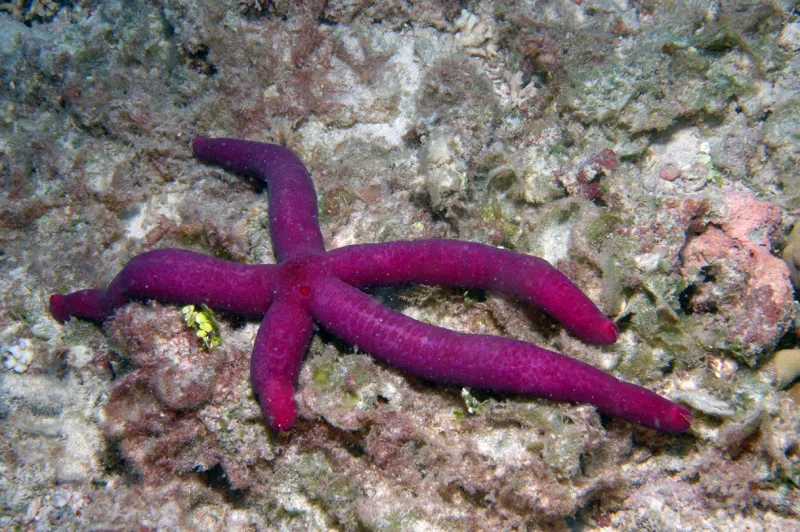

Purple Sea Star

Credit: Gustav Paulay, Florida Museum of Natural HistoryThis bright purple sea star is a new species found by the Census of Coral Reef Ecosystems, a project of the Census of Marine Life. This particular specimen was seen on the reefs of the French Frigate Shoals during the day, and is about a foot long.

Sargassum fish from the Waters of South Korea

Credit: Dr. Sung KimThe sargassum fish (Histrio histrio) is a member of the frogfish family (Antennariidae) and typically lives in open waters near floating sargassum seaweed, which offers camouflage. Although capable of swimming quite rapidly, this fish often crawls through the sargassum weed, using its pectoral fins like arms.

The Squidworm - A New Species

Credit: L. Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Inst. (WHOI) (www.cmarz.org)In the Coral Triangle, a biodiverse area between Indonesia and the Philippines, scientists discovered this swimming polychaete (bristly worm), which they have dubbed the "squidworm." Using a remotely operated vehicle, the researchers with the Census of Marine Zooplankton (CMarZ), a project of the Census of Marine Life, dove 1.8 miles (2,800 meters) to first discover Teuthidodrilus samae in 2007. The squidworm is named such because of its 10 tentacle-like appendages on its head, which are each longer than its whole body. It uses these to collect particles and detritus falling through the water, often called "marine snow," for food. See more photos of cool zooplankton collected by the researchers in this zooplankton biodiversity slideshow.

Spider Conch from China

Credit: Dr. Julian Finn, Museum VictoriaThis beautiful spider conch (Lambis chiragra) was collected by Census of Marine Life scientists conducting research near China.

Arctic Sea Cucumber

Credit: Antonina Rogacheva, Shirshov Institute of Oceanology, MoscowThis species of deep-water sea cucumber (Elpidia belyaevi) was discovered by Census of Marine Life researchers in the frigid waters of the Arctic. Since the 1800s, researchers observed sea cucumbers similar to this one in the Arctic at all depths, from shallow to deep, and assumed they were all the same species, Elpidia glacialis. But after the Census, researchers think that E. glacialis lives mostly in shallow water, while the new species E. belyaevi lives in the mid- and deep ocean.

Zombie Worms Eating Whale Bone

Credit: Yoshihiro Fujiwara/JAMSTECZombie worms (Osedax roseus) eat away at the bones of a dead whale that has fallen to the seafloor in Sagami Bay, Japan. These bizarre worms rely on whale bones for energy and are what scientists call “sexually dimorphic”—the male and female forms are markedly different. In this case, the males are microscopic and live inside the bodies of the female worms! This allows females to produce many, many eggs to disperse across the seafloor. Few of these will land close enough to sunken bones to survive.

Deep Water Octopus in the Gulf of Mexico

Credit: I. MacDonald (in Gulf of Mexico–Origins, Waters, and Biota. Vol. 1. Biodiversity. Felder, D. L. and Camp, D. K. (eds.) 2009. Texas A&M Press.)This brilliant red octopus (Benthoctopus sp.) was photographed at more than 8,800 feet (about 2,700 meters) in Alaminos Canyon in the Gulf of Mexico. See more photos of wild creatures encountered during the Census of Marine Life.

Atolla Jellyfish from the Waters of Japan

Credit: JAMSTECThe ROV Hyper Dolphin caught this deep-sea jelly (Atolla wyvillei) on film east of Izu-Oshina Island, Japan. When attacked, it uses bioluminescence to "scream" for help—an amazing light show known as a burglar alarm display. Visit the Encyclopedia of Life to learn more about these wild jellies.

Venus Fly-Trap Anemone in the Gulf of Mexico

Credit: I. MacDonald (in Gulf of Mexico–Origin, Waters, and Biota. Vol. 1. Biodiversity. Felder, D. L. and Camp, D. K. (eds.) 2009. Texas A&M Press.Like its terrestrial namesake, the Venus fly-trap anemone (Actinoscyphia sp.) sits quietly and waits for food to drift into its outstretched tentacles, which are lined with stinging harpoons called nematocysts. Of course, this is how most anemones behave; this one just happens to look a like like the Venus fly-trap plant! They are deep-sea animals; this one was photographed at roughly 4,900 feet (1500 meters) by researchers with the Census of Marine Life. See more photos from the Census of Marine Life.

Transparent Sea Cucumber

Credit: Laurence Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution/CMarZ, Census of Marine LifeCensus of Marine Life researchers discovered this unusual transparent sea cucumber (Enypniastes sp.) in the Gulf of Mexico at 2,750 meters depth. It creeps forward on its tentacles pretty slowly, at around 2 centimeters per minute, while sweeping detritus-rich sediment into its mouth. It's so transparent that you can even see its digestive tract winding through its body! See more cool zooplankton discovered by the Census of Marine Life, or learn more about the deep sea.

A Striped Deep Sea Worm

Credit: © Hauke Flores, AWIIn Antarctica's Southern Ocean swims a beautiful polychaete (bristly worm) called Tomopteris carpenteri, which is adorned with alternating red and transparent bands. The largest species in its genus, it it found throughout the water column, including the deep sea, where this photo was taken by Census of Marine Life researchers. Most polychaetes swim in the open water using their parapodia, the comb-like appendages coming off their sides, but some bury into the seafloor. Many members of the Tomopteris genus are bioluminescent and can shoot sparks off their parapodia when threatened.

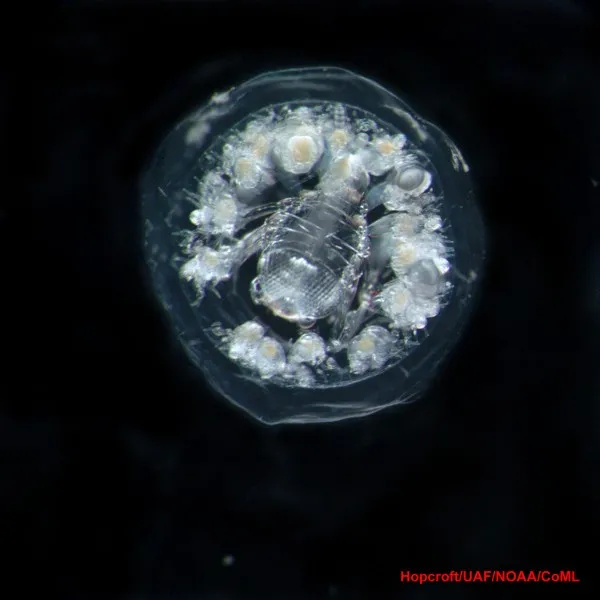

Amphipod: Salp Invader

Credit: R. Hopcroft, University of Alaska - Fairbanks (UAF) (www.cmarz.org)Can you spot the amphipod (Phronima atlantica) in the below photo? She's the transparent lobster-looking animal in the middle, surrounded by her own eggs -- inside a sac that once was the "barrel" of a salp. Mothers in the genus Phromina attack the barrel-shaped salps, hollowing out the inside of their sac body before laying their eggs inside. They use the barrel as an egg case to contain the eggs, and then hatched larva, so she can care for them in the open ocean.

This amphipod was photographed by researchers from the Census of Marine Zooplankton in the Sargasso Sea.

See more photos of cool zooplankton collected by the researchers in this zooplankton biodiversity slideshow.

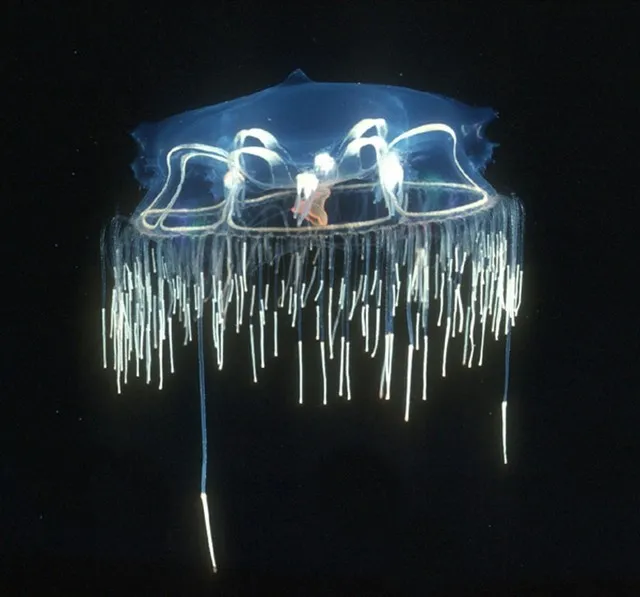

Midwater Jellyfish

Credit: Marsh Youngbluth/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeA fringe of short tentacles surrounds the flattened bell of this tiny, transparent jellyfish (Halicreas minimum), which can be found at depths up to 984 feet (300 meters). But it would be hard to spot: the bell grows up to just 4 centimeters (2 inches) across! See more deep ocean diversity and explore more about jellyfish biodiversity.

Unidentified Comb Jelly

Credit: Marsh Youngbluth/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeThis jelly’s red color provides camouflage in the deep ocean. Red light rarely reaches those depths, and most deep-sea animals have lost the ability to see red. The long, complex tentacles of this unidentified comb jelly (Order Cydippia) have sticky cells that can snag prey, and then retract. Learn more about comb jellies and click through a slideshow of deep ocean animals.

Sea Stars and Urchins off Antarctica

Credit: Brenda Konar, University of Alaska - FairbanksSea stars (Odontaster validus) and sea urchins (Sterechinus neumayeri) spread over an algae-covered seafloor off the coast of Antarctica. These two species are often found living in association with one another, and they were studied (together and separately) by NaGISA, the Natural Geography In Shore Areas project, during the Census of Marine Life.

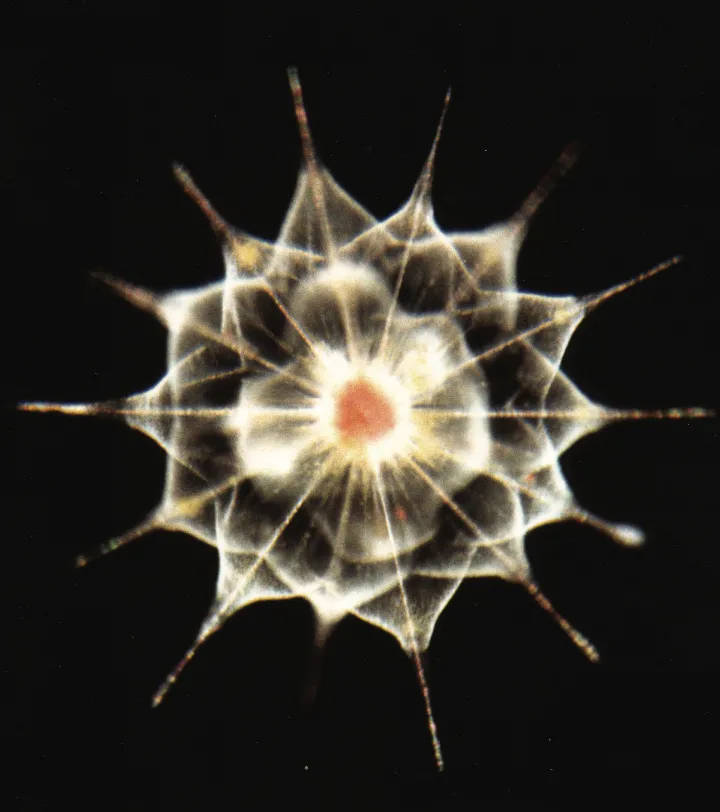

Marine Microbe from the Open Ocean

Credit: Image used under license to Marine Biological Laboratories

Deep Sea Copepod

Credit: R. Hopcroft, University of Alaska - Fairbanks (www.cmarz.org)This copepod (Gaussia princeps) was collected deeper than 1000 meters in the Sargasso Sea by Census of Marine Zooplankton (CMarZ) researchers in April 2006, as part of the 10-year Census of Marine Life. However, specimens of this species have been collected in all the world's oceans at many depths: in the Caribbean, it has been found at depths as shallow as 25-50 meters!

G. princeps is a bioluminescent species, with both males and females producing blue light. Its light is bright enough that molecular biologists use the bioluminescent pigment as dye in the lab to help them visualize their experiments.

Reference: Suarez-Moralez, E. 2007. The mesopelagic copepod Gaussia princeps (Scott) (Calanoida: Metridinidae) from the Western Caribbean with notes on integumental pore patterns. Zootaxa 1621: 33–44. (PDF)

See more photos of cool zooplankton collected by the researchers in this zooplankton biodiversity slideshow.

Jellyfish, or Siphonophore Colony?

Credit: L. Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (www.cmarz.org)This colony of Rosacea may look like a single jellyfish, but it is actually a large group of smaller siphonophores clustered and living together. In fact, the zooids (individual siphonophores living in the colony) cannot survive on their own. This specimen was photographed by the Census of Marine Zooplankton, a project of the Census of Marine Life, in the Sargasso Sea in April 2006.

A Rosacea colony's long tentacles extend a meter away from the main body and contract when disturbed by potential food items. The bead-like dots are stinging cells (nematocysts) that immobilize and kill their prey.

See more photos of cool zooplankton collected by the researchers in this zooplankton biodiversity slideshow, and learn more about jellyfish, comb jellies and other gelatinous ocean animals.

New Jelly Species: 'Bathykorus bouilloni'

Credit: K. Raskoff, Monterey Peninsula College, Hidden Ocean 2005, NOAAMany expeditions in the Arctic reveal new species, such as this jellyfish Bathykorus bouilloni, which, strangely, has only four tentacles! Dr. Kevin Raskoff from California State University, Monterey Bay first captured one in the deep Arctic in 2002 and thought it was rare. But when he returned in 2005 with NOAA and the Census of Marine Life, he and his crew found themselves in a swarm of the jellies! Read Dr. Raskoff's mission log about the experience, and how he found that the jellies weren't just a new species, but a new genus.

A Swimming Snail

Credit: R. Hopcroft, University of Alaska - Fairbanks (UAF) (www.cmarz.org)Sea butterflies (also called pteropods) are sea snails aptly named: they are shelled marine snails, each with a foot like a wing, that swim in the water column like butterflies. This one, Atlanta peronii, is very small: the biggest specimen on record was less than half an inch (11 millimeters) long! They are completely transparent, so you can see all their organs, and have shiny black eyes.

This A. peronii was observed in the Sargasso Sea by the Census of Marine Zooplankton.

See more photos of cool zooplankton collected by the researchers in this zooplankton biodiversity slideshow.

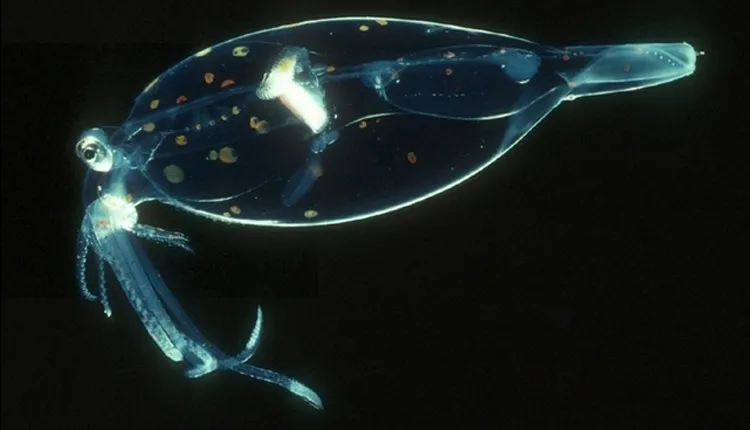

Cockatoo Squid

Credit: Marsh Youngbluth/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeThis transparent cockatoo squid (Leachia sp.), also known as a glass squid, lives in the depths of the ocean and has many adaptations to help it survive there. It retains ammonia solutions inside its body that give it a balloon-like shape and help it float. It has large eyes and pigment-filled cells, or chromatophores, that look like polka dots and serve as camouflage.

See more pictures of bioluminescent animals that light up in the dark ocean water, and other organisms found in the deep ocean by the Census of Marine Life.

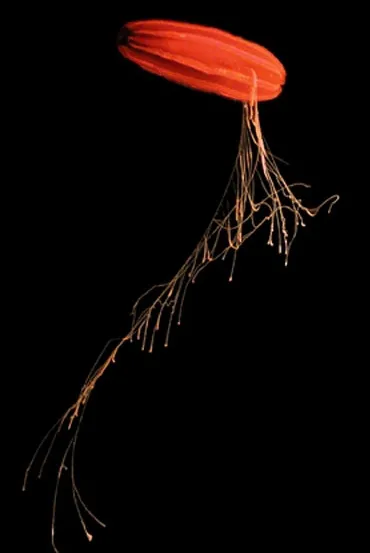

Red Mid-Water Comb Jelly

Credit: Marsh Youngbluth/MAR-ECO, Census of Marine LifeLike this ctenophore (Aulococtena acuminata), many animals that live in the midwater zone are red—making them almost invisible in the dim blue light that filters down from the sea surface. This small comb jelly snares prey with its two short tentacles. Read more about the deep sea and comb jellies.

Close-up View of Salps

Credit: L. Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Inst. (WHOI) (www.cmarz.org)This close-up view of salps, which have aggregated together into a long chain, have brilliant red guts from eating red plankton. They were observed by researchers with the Census of Marine Zooplankton in the Sargasso Sea.

Salps are sac-like, tubular organisms that spend part of their life as individual oozoids (a single, short tube with one red gut), reproducing asexually, and then link up in the aggregate phase, forming long chains. Once attached, the chain of individual oozoids swims and feeds together, and if they run into another chain, will reproduce sexually.

See more photos of cool zooplankton collected by the researchers in this zooplankton biodiversity slideshow.

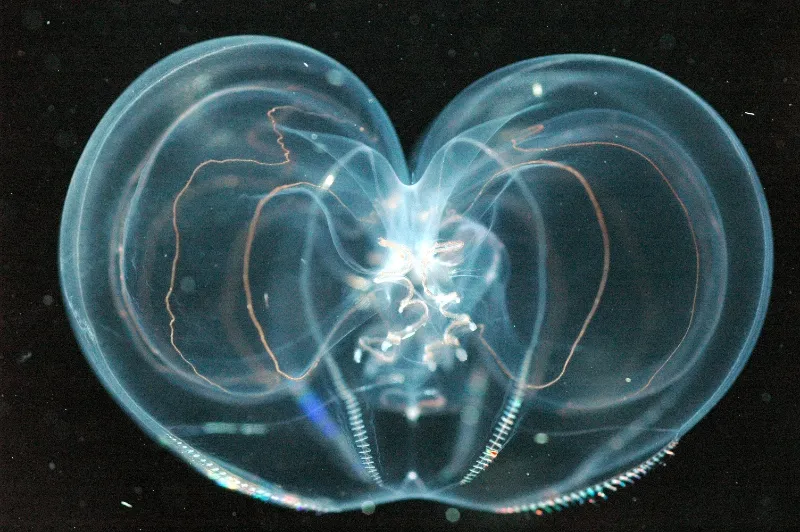

A Ctenophore Feeds

Credit: L. Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Inst. (WHOI) (www.cmarz.org)The comb jelly (ctenophore) Thalassocalyce inconstans is found in shallow to deep water in the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and sometimes in warmer Pacific Ocean waters off the coast of California -- although this one was photographed in the Sargasso Sea by Census of Marine Zooplankton researchers.

T. inconstans has a very different feeding behavior than other ctenophores. Most ctenophores use muscles to suck in large volumes of water to capture prey. But T. inconstans has little muscle; instead, it waits until a euphausiid (small crustacean) or copepod accidentally swims inside its bell, where it sticks to the mucus-covered inner surface. Then the ctenophore closes its bell shut very fast -- in less than half of a second!

See more photos of cool zooplankton collected by the researchers in this zooplankton biodiversity slideshow.

Reference: Swift, HF, Hamner, WM, Robison, BH, Madin, LP. 2009. Feeding behavior of the ctenophore Thalassocalyce inconstans: revision of anatomy of the order Thalassocalycida. Marine Biology 156, 1049-1056. (PDF)