Coral Under Pressure: Monitoring Bleaching In Real Time

Vibrantly colored corals, with small fish darting about and sharks looking for their next meal. This vision of a healthy coral reef can very quickly be replaced by a lonely white landscape of dead and dying corals. When water gets too hot (usually 2°F/1°C above the normal maximum temperature), the relationship between corals and the tiny algae that live within corals breaks down. Without their algae, the corals lose their color, hence the name coral bleaching. This is a problem because the algae provide food to their coral hosts. The corals will eventually die if temperatures stay too hot for too long, leaving a stark underwater landscape.

This year, with a double whammy of a particularly strong El Nino event on top of general global warming, waters are expected to simply get too hot for some corals to handle. This year’s coral bleaching event is already being called a global bleaching event, only the third ever recorded, and it could lead to significant numbers of corals dying around the world.

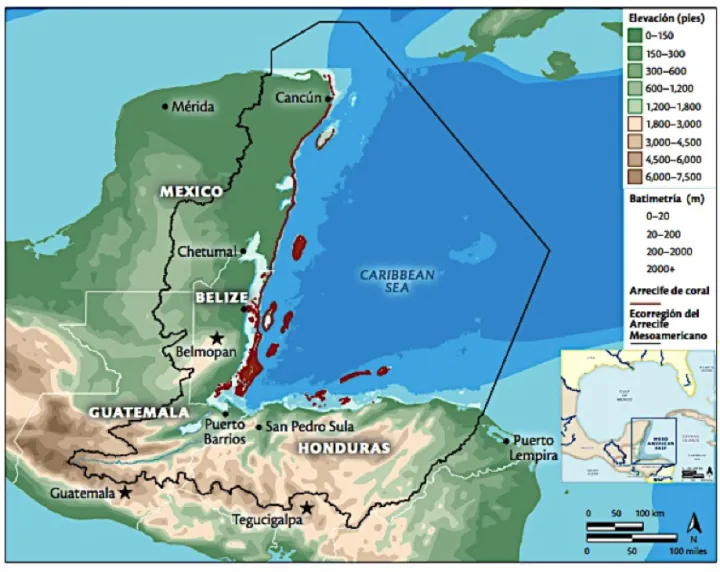

The Mesoamerican Reef extends over 600 miles (1000 km) through the crystal waters of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras and includes the Western Hemisphere’s longest barrier reef. It is also home to the Smithsonian’s Healthy Reefs for Healthy People Initiative (HRI), a unique international collaboration of coral reef-focused research, management and conservation organizations dedicated to safeguarding the Mesoamerican Reef. HRI now includes 65 local, national and international partners. In October, with emergency funding from Code Blue and the Summit Foundation, HRI initiated a Coral Bleaching Emergency Response Monitoring Plan to track the impact of the global bleaching event on the Mesoamerican Reef. This large effort involves 19 partner organizations and began in October 2015. The goal is to measure the extent of coral bleaching in different areas of the reef and in different species of coral.

Early results found that this bleaching event has not so far affected the Mesoamerican Reef region as much as it has many reefs in the Pacific Ocean. The corals that grow in thin, flat, plate-like shapes are among the most bleached. The massive boulder-like corals are also highly affected. Some of the hardest-hit sites are close to the coastline, where additional stressors—overfishing and run-off from land that carries sediments, nutrients, and improperly treated sewage—are likely compounding the stress on these corals caused by the too warm water.

Monitoring is occurring at 103 different sites that were selected to cover areas that are likely to differ in bleaching severity based on models developed by University of Queensland and Smithsonian researchers. Research teams will follow up in January of 2016 to determine if the bleaching event has waned, and evaluate the extent of coral death– if any. The results will help validate the model and improve researchers’ capacity to predict which reefs are most and least susceptible to coral bleaching.

Meanwhile, the world leaders and climate negotiators are dealing with their own stressors. Discussions continue to forge an agreement that could keep the global temperature increase at or under 2 degrees Celsius, although this may still be too warm for some corals to survive. Even better for reefs would be holding the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees, which coral scientists consider a much safer limit. The success of these efforts is far from guaranteed. This uncertainty highlights how local reef conservation efforts, which can make reefs more resilient in the face of warming waters, are all the more important in the coming decades if we are to see these magnificent and valuable ecosystems thrive into the next century.

Editor's note: Ian Drysdale, the Honduras Coordinator for the Healthy Reefs for Healthy People Initiative, also contributed to this post.