How Marine Life Responds When the Sky Goes Dark

Reviewed by Carole Baldwin, Smithsonian NMNH

If the sky briefly went dark during the middle of the day in ancient Greece, people took this to mean that the gods must be angry. Around the world and throughout history, people have had countless variations of these beliefs: the sun must be angry, the sun is sick, or the sun has dropped its torch. An unexpected dark sky brought fear, amazement, and wonder.

Now, humans know that a sudden darkening of the sky can be due to a meteorological event called a solar eclipse, which occurs when the moon passes between the Earth and the Sun. According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), there are at least two solar eclipses per year on earth, and every two years about one of these is a “total solar eclipse” in which the path of the eclipse is temporarily cast into complete darkness.

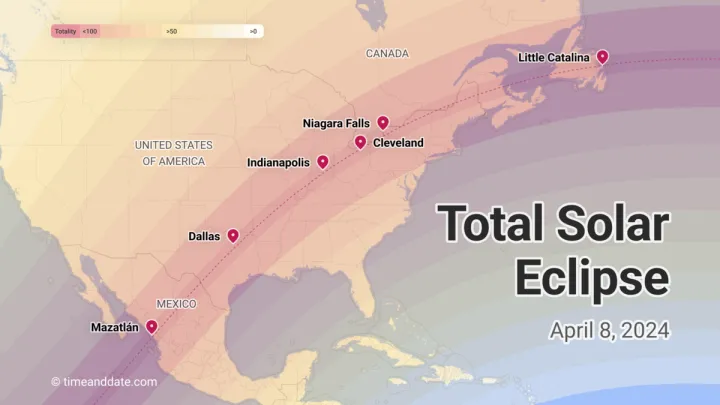

On April 8, 2024, large swaths of North America will experience a total solar eclipse, during which the sun’s light will be completely blocked from certain perspectives on Earth. Since the moon is closer to earth, the eclipse will last slightly longer than the recent eclipse in 2017. The eclipse path will cross over parts of Mexico, the United States, and Canada, leaving these regions in temporary darkness during the usually light hours of the day. In these areas, people can gather to watch the eclipse — using “eclipse glasses” to protect their eyes.

The path of the eclipse will also touch vast areas of ocean, beginning in the South Pacific Ocean and reaching the North Atlantic Ocean. How the marine life along this path will react is a subject of interest and some research. Here’s what we know so far about how marine species will react to a total eclipse, and what questions scientists are hoping to answer during the April 8 total solar eclipse.

Scrambled Sleep Schedules

When a region on Earth experiences a total eclipse, it appears as if nighttime has fallen. For humans, this brief darkness is simply an oddity with minimal effect on our daily routine. But for some animals, the darkness caused by an eclipse can trigger the responses that are typical of night. In the case of diurnal species (those that are active during the light hours of the day), this means going to sleep, while for nocturnal species (those that are active during dark hours of the night), this means waking up when the sun disappears behind the moon.

During the February 1998 total solar eclipse that touched the Galapagos islands, a group of scientists decided to study how fish in the area responded. They discovered that decreased light intensity caused diurnal fish to rapidly adopt nighttime behavior and caused nocturnal fish to gradually leave the cover of their daytime habitats.

An early study from the 1905 total solar eclipse in England found that solar eclipses are a profitable time to go fishing, since so many fish come to the surface at dusk to find their evening meal. The eclipse, mimicking dusk, tricks fish into thinking it is time for this meal.

The underlying factor in responses to the eclipse is whether sleep schedules are based on external stimuli (i.e. “exogenic”) or internal stimuli (i.e. “endogenic”). For humans, the sleep cycle is largely internal; we have a circadian rhythm that keeps track of the time no matter what the sun is doing. This internal clock is what causes jet lag when travelling, where your body follows its habitual cycle rather than following the new cues of the sun in a different location. But for some animals, waking and sleeping cycles are almost entirely dependent on cues from the sun.

Solar eclipses can help scientists determine if an animal has an endogenic or exogenic sleep schedule. If the animal exhibits normal behavior during a daytime darkening of the sky — like humans — it likely has a strong internal (endogenic) clock. If it changes behavior in response to decreased light, like fish have been shown to do, it likely has a light-dependent or exogenic clock.

Scientists will be watching ocean habitats again this year to see how fish respond, but observations from past eclipses suggest that in the short switch to darkness fish will flip their sleep schedules in response to the hidden sun.

Modified Migration

The world’s largest migration event isn’t a yearly movement of cranes, geese, or even wildebeest — it is a daily movement in the ocean of billions and billions of tiny marine organisms from lower depths toward the sea surface in response to signals from the sun. These small organisms — called zooplankton — are a large category of small marine organisms that eat other organisms to survive.

This daily movement, called Diel Vertical Migration or DVM, occurs at sunrise and sunset. At sunset, zooplankton swim up to the surface of the ocean to feed at night, when they are protected from their predators by darkness. Then, before the sun rises, they return to the safety of the deep ocean.

To see whether this event is triggered by the sun, scientists decided to track DVM during an eclipse to see how they would respond to this false night.

One group of scientists measured the movement of zooplankton during the 2017 eclipse off the coast of Oregon and found that the migration occurred during the eclipse as it would at dusk. The zooplankton migrated up as the sky darkened then returned to the deep ocean as the sun reappeared from behind the moon.

An earlier study of the 1963 eclipse that crossed much of the United States similarly found that zooplankton migrated in response to an eclipse. They also glowed. This study also found that the miniature marine organisms that typically exhibit bioluminescence at nighttime also start to glow in the dark during an eclipse.

These studies show that, like the sleep cycles of fish, zooplankton migration and bioluminescence are controlled by exogenous factors like the availability of sunlight rather than endogenous factors like the animals’ internal clock.

Chaos and Commotion

While some animals seem to calmly respond to the sun’s abnormal cues, others are thrown into confusion and chaos at the onset of a solar eclipse. A spell of darkness at midday is surely an unsettling occurrence for animals with little understanding of astronomy or the solar system.

In a study conducted at the Riverbanks Zoo in Columbia, South Carolina during a total eclipse in 2017, experts tracked animal behavior to see how it changed over the course of the eclipse. The scientists found that multiple animals, including the flamingo and the Komodo dragon, exhibited high levels of restlessness and anxiety.

They noticed pacing, swaying, and group consolidating that indicated increased vigilance and anxiety, especially in the flamingoes, which swarmed together at the onset of the eclipse. It is likely that other wild animals also react similarly when the sun disappears.

Delivering Data

Although humans understand what an eclipse is and how best to react (don’t look at the sun!), scientists are always looking to learn more about how marine animals will react. No doubt they will continue to unlock more mysteries of how solar eclipses affect ocean and animal life on April 8.