An Irrepressible Wave

How Women in Ocean Science Transitioned from Unpaid Volunteers to Chairs of Departments and Directors of Research Institutes

The ocean sciences have been an important research priority at the Smithsonian from the beginning, and central to those scientific discoveries are a group of determined individuals—women. Early on in the history of the Smithsonian’s National Museum (the predecessor to the National Museum of Natural History) women contributed to ocean science behind-the-scenes as unpaid volunteers, though often they carried out roles and positions that would be considered full-time-jobs by today’s standards. Many earned their positions through their relationship with brothers, fathers, or spouses—a foot in the door that allowed them to prove their worth. As time progressed (and the National Museum evolved into the National Museum of Natural History), a transition in the perception of women in the workforce meant women were hired for their scientific merit and many obtained positions in leadership roles. The transitions over time reflected many aspects of work life--from how women were hired, to how they were paid, and how they were perceived by society and male colleagues.

The Smithsonian Institution is Established

James Smithson wills his estate to the US to found an “establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men.” How this will manifest is up for debate in Congress, but the Institution originates as a place to perform and exhibit scientific research.

James Smithson in 1816. He donates the seed money that funds the Smithsonian Institution. (Smithsonian Archives)

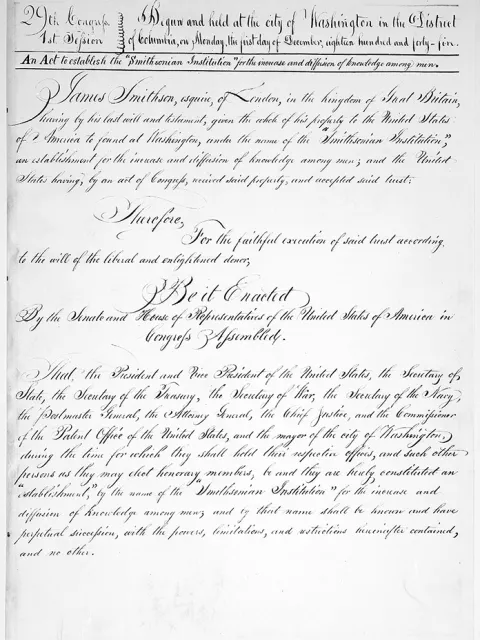

The "Act to Establish the 'Smithsonian Institution,' for the Increase and Diffusion of Knowledge among Men," which is passed by Congress in 1846 after 8 years of debate. It is subsequently signed into law by President James K. Polk. (Smithsonian Archives)

There is one male curator and there are zero female curators at the Smithsonian

The number of curators steadily increases over time. The percentage of curators that are female also increases.

Every 50 years, we can see a notable uptick in the percentage of women curators across all Smithsonian museums and the National Zoo.

The US Commission of Fish and Fisheries is established

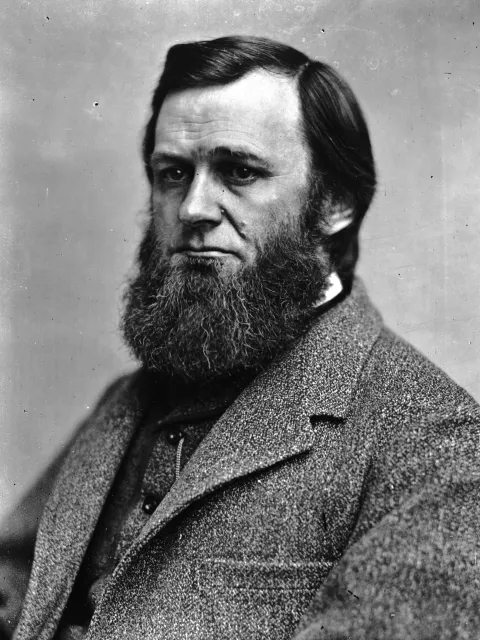

Spencer Fullerton Baird, the Smithsonian’s first curator from 1850-1878 who goes on to be Smithsonian Secretary from 1878-1887, creates the US Commission of Fish and Fisheries to investigate the causes for the decrease of commercial fish, to recommend remedies, and to oversee restoration efforts.

Spencer Fullerton Baird in 1867. (Smithsonian Archives)

The women at this time are pioneers. It is uncommon for women to be in the workforce at all, let alone in science.

This is a time when blatant sexism is common and fairly universal, which is seen through newspaper clippings discussing some of these women’s achievements. These women often begin or spend their whole careers with the Smithsonian as volunteers. When paid, it is not much. Many also begin work at the Smithsonian because of their relationship to a man – like a brother or husband who works there – rather than due to actual achievements; there is no other way to break into the field otherwise.

Despite these difficulties, these women all make significant impacts to their respective fields throughout their careers.

Mary Jane Rathbun joins the Smithsonian in the Department of Marine Invertebrates

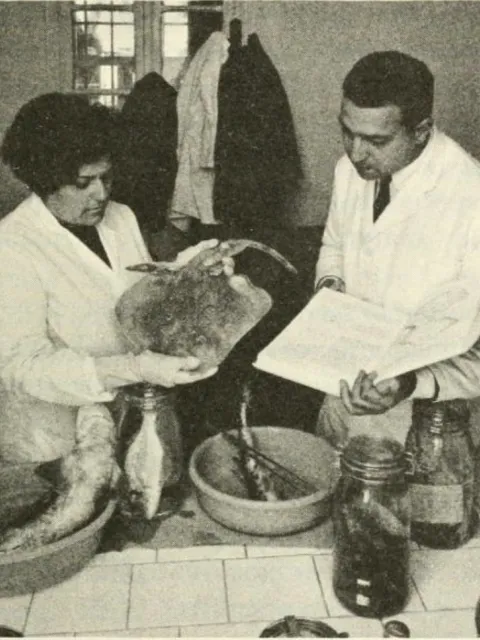

Rathbun begins her scientific career volunteering for her brother, Richard Rathbun (Curator of Marine Invertebrates), in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, where she sorts, labels, and records specimens from 1881 to 1884. After this stint, Spencer Fullerton Baird, then Smithsonian Secretary and Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries, grants her a clerkship in the Department of Marine Invertebrates.

As a volunteer, her career begins unpaid. Once a clerk, she is paid, albeit modestly.

Rathbun (left) in Woods Hole in the 1890s. (Smithsonian Archives)

Rathbun at her desk in 1894. (Smithsonian Archives)

Harriet Richardson joins the Smithsonian in the Department of Marine Invertebrates

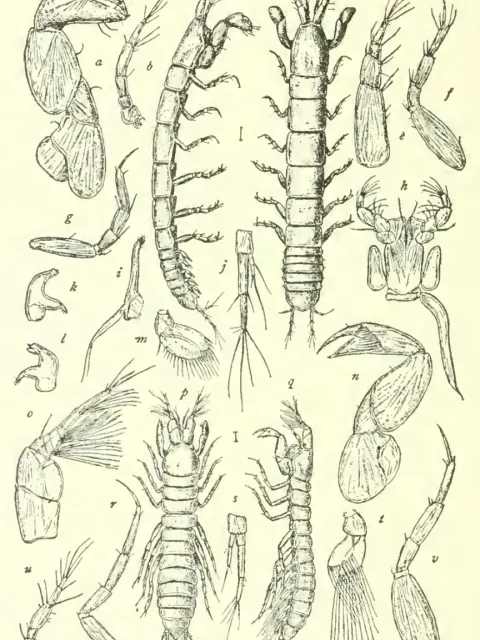

Richardson is the second female carcinologist (someone who studies crustaceans) after Rathbun. She studies isopods, a kind of crustacean, and publishes an authoritative and notable 800-page monograph in 1905, which includes descriptions of all known isopods in North America at the time, which is still referred to today.

After a series of deaths of the leading scientists studying isopods, there is a vacuum of research being done on these small creatures. Richardson fills that vacuum.

The entirety of her career at the Smithsonian is unpaid.

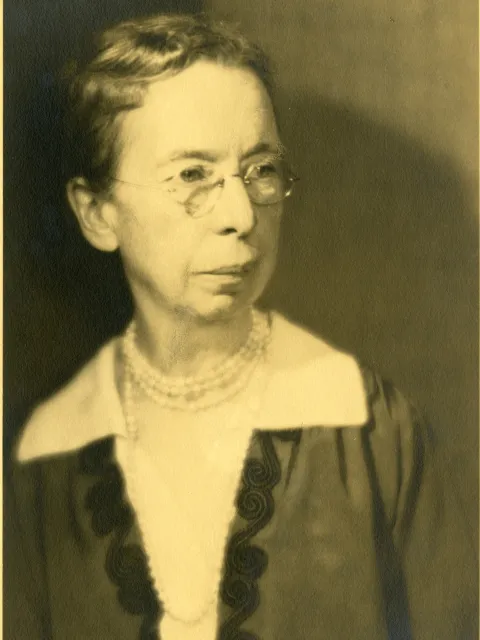

Harriet Richardson’s college graduation photograph in 1896. (Smithsonian Archives)

An illustration from Richardson’s 1905 monograph, depicting different parts of a specific isopod, Leptognathia longiremis (page 20). (A monograph on the isopods of North America, 1905)

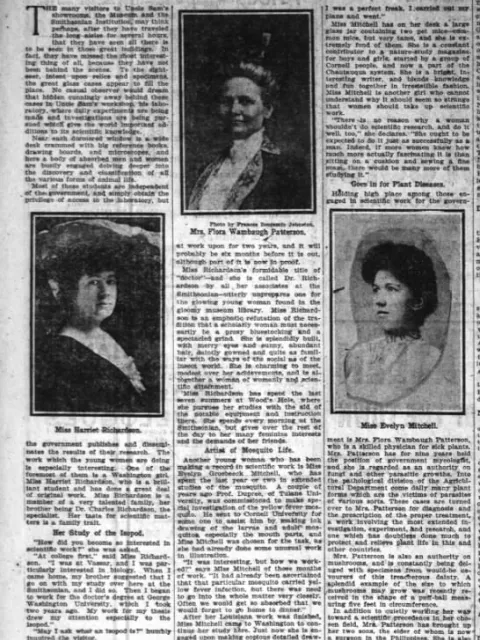

A Washington Post story about women scientists at the Smithsonian publishes

This article illustrates commonly held attitudes towards professional women at the time – like a focus on her physical attributes and marital status. Richardson is characterized in the following quote from the article: “Miss Richardson’s formidable title of ‘doctor’—and she is called Dr. Richardson by all her associates at the Smithsonian—utterly unprepares one for the glowing young woman found in the gloomy museum library. Miss Richardson is an emphatic refutation of the tradition that a scholarly woman must necessarily be a prosy bluestocking and a spectacled grind. She is splendidly built, with merry eyes and sunny, abundant hair, daintly gowned and quite as familiar with the ways of the social as of the insect world. She is charming to meet, modest over her achievements, and is altogether a woman of womanly and scientific attainment.”

The newspaper article in question. Richardson is on the left. (via Newspapers.com)

Mary Jane Rathbun achieves her highest position of Assistant Curator of the Division of Marine Invertebrates, and “retires” from the Smithsonian

Rathbun requires an assistant in order to complete her first monograph about crabs, but the department cannot (or will not) fund another person’s salary. She resigns as full assistant curator, with the understanding that her salary will be given to her new assistant. She continues to work at the Smithsonian, unpaid, until 1940.

Mary Jane Rathbun is notable as the first female carcinologist, and one of the first women in science at the Smithsonian. She reaches a fairly high position at the museum, even by today’s standards.

The work she does describing and naming over 1,000 species during the course of her career lays the groundwork for the record systems still in use. Over the course of her career, Rathbun writes four monographic handbooks describing and naming different species of crabs.

An illustration of a crab from Rathbun’s work, “Brachyura and Macrura of Porto Rico,” 1902. (via SciHi Blog)

The National Museum of Natural History finishes moving into its current building on the National Mall

The museum was originally housed in the Smithsonian Castle, until 1881. It then briefly moved to the Arts and Industries Building until 1910, when it finally moves into its current home.

The main entrance and rotunda of the Natural Museum of Natural History. (Smithsonian Archives)

Harriet Richardson retires from the Smithsonian

Richardson marries William Searle and has a disabled child, who becomes her new focus. She does not publish much after this (only around 5 papers), despite having published around 75 previously during her career. As can still happen today, the demands of childcare competed with Richardson’s career ambitions and success.

Pearl Lee Boone joins the Smithsonian

Boone, like Rathbun and Richardson before her, is a carcinologist. She is the first to be hired entirely based on her scientific ability and not because of her connections to a man already working there, and the first to be paid from the start.

Here is a photograph of Pearl Lee Boone during her time at the Smithsonian. Part of the caption reads, “That she does not confine her attention to cephalopods is evident from the cut, where altho an octopus and a squid appear as cephalopodous objects for her study and investigation, the bunch of lilies in the background shows that she has not lost the sense of beauty, so strong in her sex, and has at least an aesthetic feeling for botany.”

Much like the article about Richardson, despite her success as a scientist and researcher, the fact of her gender had to be a comment or caveat when discussing her work.

(via "Dendrites," Blogspot)

Lee Boone leaves the Smithsonian

Boone is accused of incompetence by Waldo Schmitt, who has her fired, and whom she, in turn, accuses of harassment. The story of her last day at the Smithsonian continues to float around the National Museum of Natural History: Waldo Schmitt ostensibly comes into the lab next to his office to find Boone smashing empty specimen bottles on the floor, the two get into a kerfuffle where he physically restrains her and she whacks him with an umbrella. Rathbun enters from another lab and throws a bucket of water on Boone, who is then escorted out by security guards. This is, at least, Schmitt’s perspective, who writes a memo to the museum’s Director describing the incident. It is unclear if implicit claims of “female hysteria” helped him embellish the story. Regardless of this story’s legitimacy, Boone’s tumultuous exit from the Smithsonian and Schmitt’s claim of her incompetence haunt her career.

After leaving the Smithsonian to work for the US Department of Agriculture, she begins publishing under the name “Lee Boone” – implying she is a man. She uses the male name to claim needing access to a collection for research, which is unfortunately denied when they realize who she was.

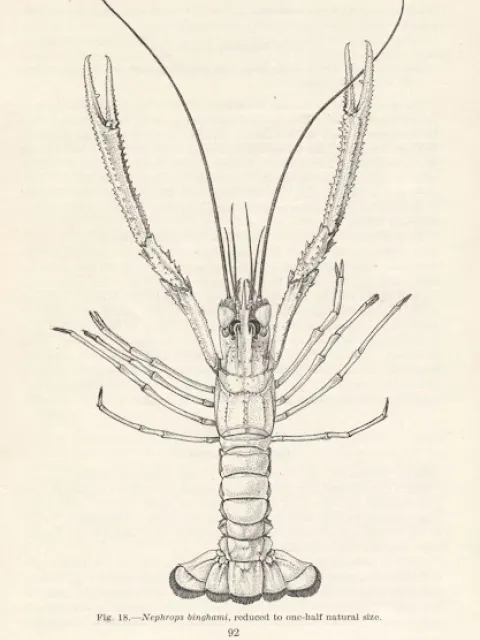

Boone's biggest scientific accomplishment is the discovery and cataloguing of a specific species of lobster considered a potential food source. Her work on it appears in the “Food and Agriculture Organization Species Catalogue.” This is her illustration of the lobster in the original bulletin in which it appeared. (via "Dendrites," Blogspot)

These women work through the context of World War II. They are more modern than their previous counterparts in some ways – like pushing to keep their research resources in new locations or starting their own oceanographical school – but there is still a long way to go to reach equality.

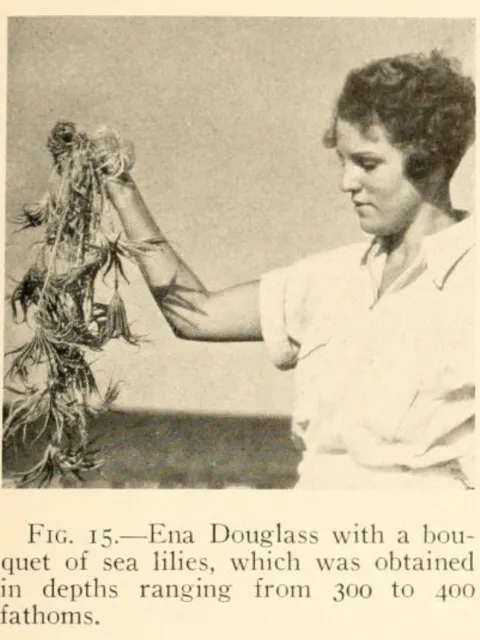

Ena and Florence Douglass contribute to the Smithsonian's Johnson Deep-Sea Expedition

At this time in history most women pursuing marine science are not allowed aboard research vessels, but many of the discoveries of the Johnson Deep-Sea expedition are thanks to the help of two young women. Ena and Florence Douglass were the invited guests of expedition funder Eldridge Johnson. Their father, Leon Douglass, was a notable inventor and colleague of Johnson’s, and he was invited aboard to help with the depth sounder and cameras essential to the research. Both Ena and Florence sorted collected specimens and managed the sounder equipment.

Ena Douglass holds a bunch of sea lilies. (Smithsonian Institution)

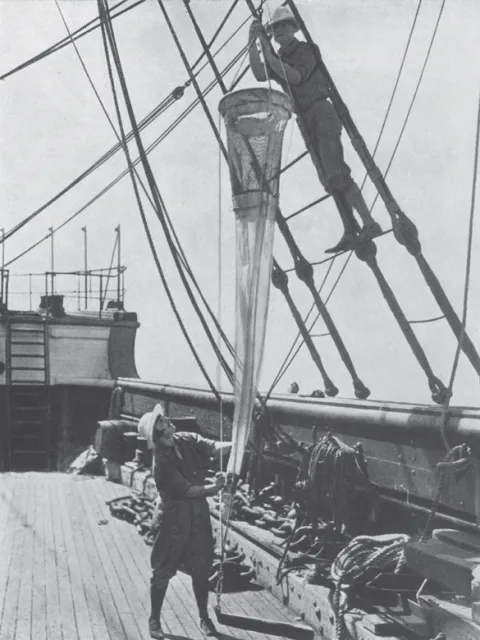

The Douglass women are seen helping with a pilot balloon. (Smithsonian Institution)

Mildred Stratton Wilson achieves her highest position of Assistant Curator of Marine Invertebrate Zoology

She holds the position until 1946. She is known for her organization, noted for leaving the department in “much better order than it otherwise would have been.”

In 1947, she gains the title of Collaborator of Marine Invertebrate Zoology, and relocates to Alaska with her husband. In order to keep researching, she gets permission to have the relevant monographs and equipment sent to her. There, she continues collecting, describing, and identifying species of copepods.

She hopes to publish a monograph of all North American species of the genus of Diaptomus of copepods. She realizes there are too many for her to complete the project, and instead revises a handbook on freshwater biology.

In 1955, she is the first woman to be awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for her work on copepods.

A freshwater copepod. (via Encyclopedia of Life)

Marie “Bobbie” Poland Fish joins the Smithsonian as a Scientific Aid in the Division of Fishes

In 1936, she and her husband founded the Narragansett Marine Laboratory, which is now the Graduate School of Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island. There, she established herself as Rhode Island’s state ichthyologist – someone who studies bony fish – and eventually is hired by the Smithsonian to classify fish.

After her brief time at the Smithsonian of only two years, she returns to the Narragansett Marine Lab to do research on the sounds marine animals make, after reading about mysterious cacophonies sailors were hearing while on the open sea. In doing so, she founds the discipline of bioacoustics, demonstrating that the ocean we tend to think of as silent can actually reach volumes of 114 decibels due to fish “talking.” She eventually works with the US Navy to help identify the difference between fish and enemy vessels based on the underwater sounds being picked up. In 1966, she is granted the Navy’s Distinguished Public Servant Award, its highest civilian honor, for outstanding service of substantial and long-term benefit to the Navy.

Newspaper reports continue their sexist traditions, belittling but celebrating her as the “affable redhead” with a “sparkling sense of humor” who researches sea sounds.

Fish breaks barriers by partaking in an ocean expedition very early on, in 1925, long before women are generally allowed on research vessels. She attends with her husband, who is also an ocean scientist, implying her savvy utilization of her resources – a husband who works in science – to achieve in her field. (via ResearchGate)

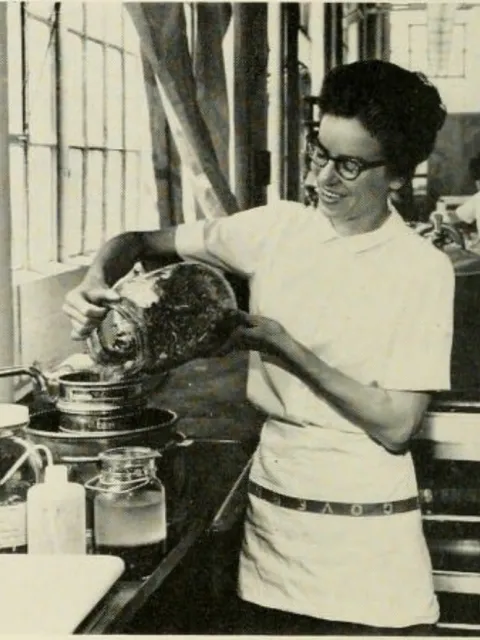

A young Fish sifting through some seaweed samples on a research vessel c. 1925. (via Wildlife Conservation Society)

The research facilities in Panama, the CZBA, officially becomes part of the Smithsonian

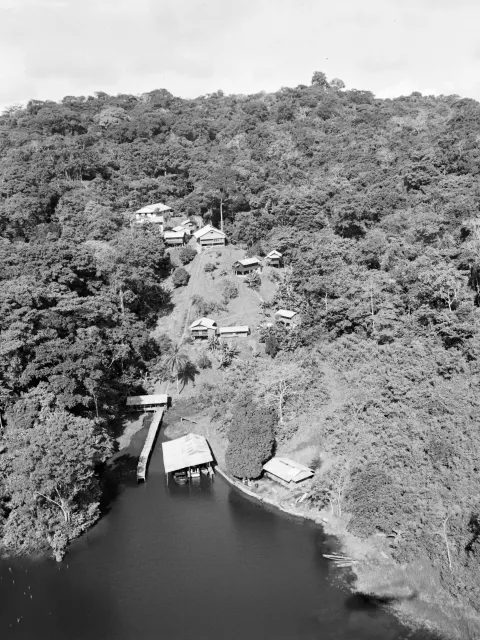

An aerial view of the Barro Coloardo Island Laboratory at the CZBA in the 1950s, shortly after the CZBA is incorporated by the Smithsonian. (Smithsonian Archives)

The view from the Barro Colorado Island Laboratory, of Gatun Lake, in 1953. (Smithsonian Archives)

The docked U.S. Snook, which ferries staff and supplies between Barro Colorado Island in Gatun Lake, and mainland Panama, c. 1950s. (Smithsonian Archives)

There are 56 male curators and 7 female curators at the Smithsonian

Since 1900, the percentage of female curators rises from 3.7% to 12.5%.

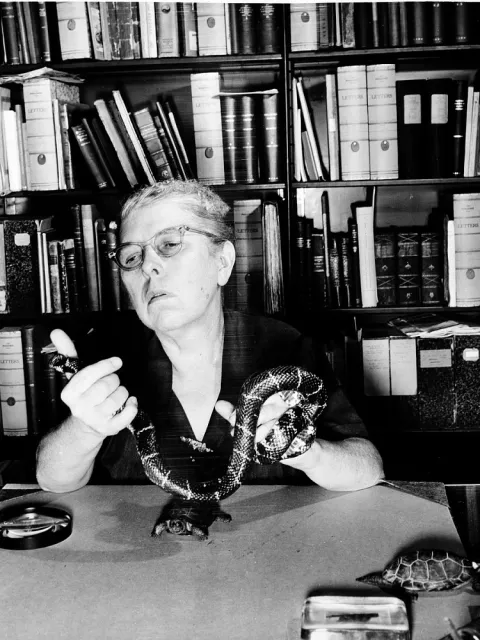

Doris Cochran in 1954, one of the few female curators at the National Museum of Natural History in the 1950s. She is appointed curator in the Division of Reptiles and Amphibians in 1956. (Smithsonian Archives)

Mildred Stratton Wilson is appointed Research Associate in the Division of Crustacea.

Wilson continues researching copepods in Alaska, and holds this role until her death in 1973.

Wilson and her husband, Charlie, in Alaska in the 1960s. (via Sleeper Family Papers, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage)

By this time, women are being hired based solely on their scientific merit, and are paid throughout the entirety of their careers. These women stay at the Smithsonian for a long time, and have impactful careers there after reaching higher levels within the organization.

Many of the over barriers women face are eliminated by this time. One such barrier is women’s exclusion from research vessels. Due to folklore claiming women on ships were bad luck, women were generally not able to join research voyages. By the 1960s, though, this barrier is broken down, opening up a world of possibility for women researchers, who are now able to do field research.

The women in this era seem much more modern than the previous ones, coming closer to attaining equality with men. This is the first time we see women reaching the rank of curator of their departments.

These women were real leaders in their fields.

An unnamed Smithsonian employee sorts invertebrates in 1965.

In 1967, Mrs. A. Ben Alaya identifies fish from the Gulf of Tunis as part of the Smithsonian's Mediterranean Marine Sorting Center.

Marian Hope Pettibone joins the Smithsonian as Associate Curator in the Division of Crustacea

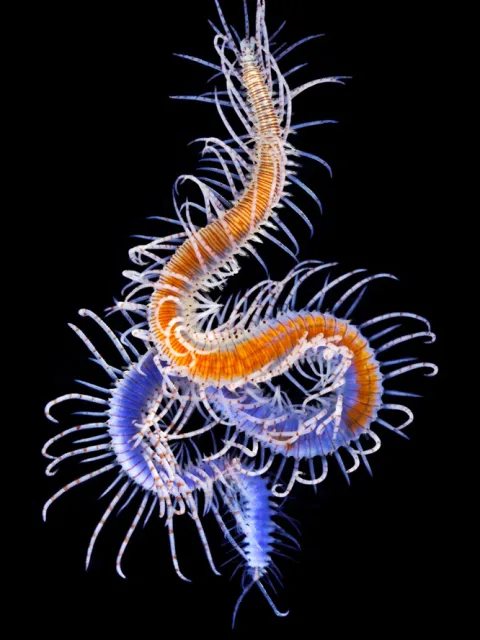

Pettibone becomes the leading authority on polychaetes, and helps spearhead the polychaete department at the Smithsonian as its first curator. She organizes the entire collection of worms that had accumulated throughout the prior hundred years, helping to arrange one of the world’s largest polychaete collections.

(© Alexander Semenov)

Some polychaete species, Cirraturlid (left) and Syllidae (right). Polychaetes are also known as bristle worms due to their many appendages that help them scoop up prey. (Courtesy of Karen Osborn)

STRI is established

The CZBA is renamed Smithsonian Tropical Resarch Institute, or STRI, to reflect its broader research scope.

STRI's administrative office in Panama City, in 1965. This office is about 25 miles from Barro Colorado Island, where the main research facilities are. (Smithsonian Archives)

Mary Rice joins the Smithsonian as Curator and Research Zoologist in the Department of Invertebrate Zoology

Like Pettibone, Rice studies marine worms, specifically sipunculans, a group descended from the polychaetes that Pettibone studies. In 1972 she relocates to Florida to do fieldwork.

Mary Rice performing fieldwork in Florida in 1975. (Smithsonian Archives)

Cuban zoologist Isabel Pérez Farfante joins the National Marine Fisheries Service laboratory at the Museum of Natural History

After she had completed her doctorate in 1948, Farfante was working as a professor in Cuba when she and her family had to flee the country. She and her husband were blacklisted by the Cuban government after her husband declined to accompany diplomat Che Guevara on a trip abroad. Fearing for their safety, the family moved to the United States with only one suitcase, leaving their possessions and lives behind in Cuba.

Isabel and her husband Gerardo Canet with Carlos de la Torre Huerta, Cuban malacologist (late 1940s).

The Smithsonian partners with Ed Link and his "Man-in-Sea" project

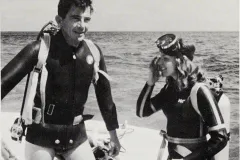

An expedition using Link's lockout submersible Deep Diver explores the Tongue of the Ocean in the Bahamas. Three women, Marion C. Link, Joyce Grob, and Sylvia Earle join the team. Unknown to the rest of the crew, Earle is five months pregnant and conducts a lockout dive.

Marion C. Link and Joyce Grob prepare to dive off of the Reef Diver during the Tongue of the Ocean expedition. (Marion C. Link)

During the Smithsonian Institution's Man-in-Sea project Giles Mead and Sylvia Earle return to the Reef Diver after a dive near Andros Island. (Marion C. Link)

Sheila Minor Huff is hired as an animal technician

She works for the US Fish and Wildlife Service's Mammal Division at the National Museum of Natural History as a biological specimen analyst. After two years she is hired by SERC where she conducts research on small-mammal populations, located on The Poplar Islands. She is the first Black person hired at SERC.

Huff was the only woman presenting at the 1971 International Conference on the Biology of Whales. She was the only person not named in the photograph. The discovery of this photograph in 2018 led to a viral, online search for her identity, which led to her eventual naming.

Joan Murrell Owens begins a museum technician position at NMNH

As a geology student at George Washington University Owens takes on a museum technician position at the National Museum of Natural History to earn money while in school. Later, once she becomes a professor at Howard University, she uses her ties to the museum to continue research using the museum's collections. Fascinated by the marine world, Owen's is unable to dive due to sickle-cell anemia, a hereditary condition that limits the amount of oxygen carried by blood cells. Undeterred, she bases her research on collections housed in the museum.

The Smithsonian Marine Station, or the SMS, is founded

Originally founded by Mary Rice in Link Port, Florida, the Marine Station is created to research Floridian marine ecosystems and life forms, specifically in the Indian River Lagoon off the eastern coast of central Florida. In 1999, the Marine Station expands and relocates to Fort Pierce, Florida.

An aerial photo of the marine station in 1995. The SMS is housed in the white barge. (Smithsonian Archives)

Mary Rice becomes director of the Smithsonian Marine Station

Founding and developing the Smithsonian Marine Station is no small feat. Rice has to get approvals and funding from both the Smithsonian and outside research organizations. She works on founding a marine station beginning in 1971, which comes to fruition 10 years later in 1981. The station is eventually relocated in 1999.

Rice is proud of the work and feels as though she is providing a service to other scientists who can come use their resources and location for research.

Rice in front of the first iteration of the SMS, housed in a floating barge at the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, in 1984. In 1999 the Marine Station opens its doors in a new building and location in Fort Pierce, Florida, where it still operates today. (Smithsonian Archives)

These women are all part of the modern wave of female ocean scientists. Over the course of this time period we see multiple women achieve the highest scientific role at the museum, chair of their respective departments. Women are also routinely curators and directors of various institutions.

Some of these more modern women speak of their experience as a woman in this field, and their different struggles and successes throughout their careers.

There is still work to be done in the field of ocean science, but the progress these women have made toward equality is remarkable.

Nancy Knowlton joins the Smithsonian at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama

At STRI she conducts notable research projects. Namely, she continues the tradition of studying marine evolution on either side of the Panamanian isthmus, focusing on snapping shrimp. She also conducts important research on the microalgae that live in coral, the Symbiodiniaceae, demonstrating that different kinds of algae are sensitive to different temperatures. Her work helps explain why so many corals are dying in the wake of climate change. This creates a new field within coral research focusing on the impact of climate change.

Nancy Knowlton filming an aquarium at STRI in 1989. (Smithsonian Archives)

A snapping shrimp from STRI, a specimen that Knowlton collects in 1990. (Smithsonian Archives)

Joan Murell Owens discovers a new genus of coral

Using the Smithsonian's Albatross collection from 1880, Owens discovers a new genus of deep sea button corals called Rhombopsammia. She eventually discovers three species from this genus, including one she names after her husband.

Letepsammia franki, the Smithsonian coral specimen used to describe the new species of button coral.

Joan Murrell Owens poses with one of her coral specimens. (Digital Howard @ Howard University)

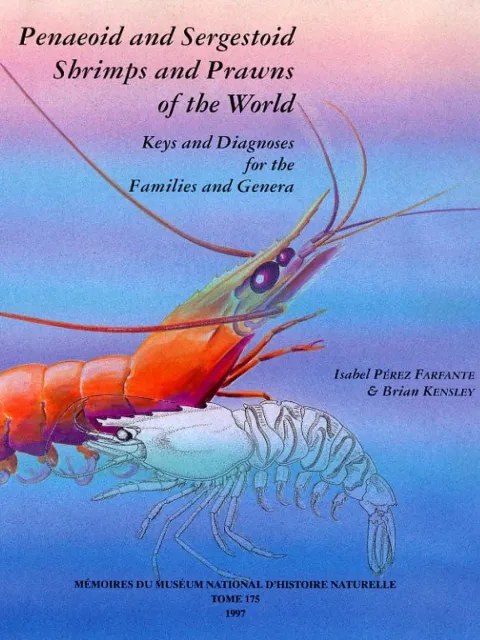

Isabel Pérez Farfante earns a role as Associate Researcher in the Division of Crustacea

Farfante holds the role until her retirement in 1997. Her most notable research is on the systematics of penaeoid shrimp.

One of Isabel’s greatest contributions, “Penaeoid and Sergestoid Shrimps and Prawns of the World: Keys and Diagnoses for the Families and Genera”, co-authored with Brian F. Kensley, brought forth new knowledge on the evolutionary history of shrimp.

Lynne Parenti joins the Smithsonian as Curator of Fishes in the Department of Vertebrate Zoology

Like Marie Poland Fish, Lynne Parenti is an ichthyologist. She studies bony fishes that live in tropical freshwater and coastal marine habitats. She focuses on systematics – the classification of organisms to understand evolutionary relationships – and biogeography – where different species have been located in space and over time.

At the Smithsonian, she identifies and discovers many taxa of fishes, and discovers new morphological characters – or characteristics-- to identify taxa

Parenti collecting specimens at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology in 2013. (Courtesy of Lynne Parenti, photo by Zeehan Jafaar)

Parenti comments on how the high-achieving women in this field are truly exceptional – and maybe have to be better than their male counterparts at what they do so they can be as high-achieving.

Carole Baldwin joins the Smithsonian as Curator of Fishes and Research Zoologist

Baldwin studies biodiversity in the midwater and deep-sea, specifically focusing on the diversity, evolution, and life cycle development of tropical fishes. She discovers and describes over 50 species of fish new to science (and counting), and identifies a new faunal zone known as the Rariphotic Zone.

Baldwin values public outreach, and sharing her knowledge and love of science with the public. Some of the outreach projects she's worked on includeGalapagos, an IMAX movie about Baldwin’s research expedition to the Galapagos islands, and a cookbook called One Fish, Two Fish, Crawfish, Bluefish – The Smithsonian Sustainable Seafood Cookbook.

Baldwin in full scuba gear. (Smithsonian Institution)

Baldwin as a young scientist. (Smithsonian Institution)

Nancy Knowlton leaves STRI and begins teaching at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at University of California San Diego

At Scripps, she founds the Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation in 2001. The first of its kind, the Center is intended to train graduate students in interdisciplinary approaches to solving problems the ocean faces by protecting ocean ecosystems in the face of climate change.

An aerial view of the beach and pier at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, where the Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation is housed. (via Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

Lynne Parenti is appointed Chair of Department of Vertebrate Zoology

She is the first woman to be appointed to this position, and feels that her achievements are appropriately recognized and rewarded in this role. Parenti feels that working for the federal government is beneficial in that it's a level playing field for men and women.

Parenti is an avid writer, and has published a handful of books, including Cladistic Biogeography: Interpreting Patterns of Plant and Animal Distributions (1986 with a 1999 second edition), Interrelationships of Fishes (1996), Ecology of the Marine Fishes of Cuba (2002), Ichthyo: The Architecture of Fish (2008), Comparative Biogeography: Discovering and Classifying Biogeographical Patterns of a Dynamic Earth (2009), and Assumptions Inhibiting Progress in Comparative Biology (2017).

This is the cover of the second edition of her first published book and most-cited work, Cladistic Biogeography: Interpreting Patterns of Plant and Animal Distributions. Parenti values being able to communicate her findings through writing.

(via Amazon)

Parenti says that the biggest obstacles she faced as a woman in the field were microaggressions that she couldn’t control – like potentially not being able to join the men at the bar after work or comments about her becoming the first woman ichthyologist president of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists.

Mary Rice is named Senior Research Scientist Emeritus and retires from directing the SMS

Rice studies Sipuncula, a kind of seaworm. In the 1990s when evolutionary developmental biology was maturing into “evo-devo” with the development of molecular genetics, Rice spearheads bringing these research practices to the study of sipunculans. In 2019, she is awarded the A.O. Kovalesky Medal to honor her extraordinary achievements in evolutionary developmental biology.

She continues doing research and fieldwork at the SMS until she passes away in 2021.

Rice with a sipunculan in 2006. (Smithsonian Archives)

Valerie Paul joins the Smithsonian as the Director of the Smithsonian Marine Station

Paul studies the chemical interactions between organisms and their environment, mainly focusing on how organisms protect themselves using chemicals and toxins – instead of, say, exoskeletons or spines. In doing this work, she helps launch the field of marine chemical ecology, combining marine ecology and chemistry.

Paul (at left in blue) at the Carrie Bow Cay field station in Belize in 2014 when Smithsonian Secretary Clough (at center right in floral shirt) visits. (Courtesy of Valerie Paul)

Paul collecting specimens in the Florida Keys. Paul has done significant research into the various kinds of bacteria that live on corals, and has identified different ways bacteria and probiotics can both help and harm corals. (Photo by Lindsay Spiers)

Paul diving in Guam. (Photo by Lindsay Spiers)

Research conducted by Paul and other SMS scientists.

Paul explains that the Smithsonian has been supportive of women throughout her career, but that there is still room for improvement in the top science positions at the Institution.

Ellen Strong joins the Smithsonian as Curator of Mollusks and Research Zoologist

Strong studies the biodiversity and evolutionary relationships of freshwater snails, cataloging species. Many snail species are becoming extinct so her work is integral in preserving as many as possible before the information is lost forever.

Strong in the field, collecting mollusk specimens. (Photo by Heather Bennet)

Nancy Knowlton returns to the Smithsonian as the Sant Chair for Marine Science, her highest position

During her tenure, she founds the Earth Optimism movement, which seeks to encourage people to engage in conservation by celebrating its success stories. She also publishes Citizens of the Sea, a book about marine life to celebrate the completion of the Census of Marine Life, which she worked on.

In 2013 she is elected to the National Academy of Sciences, one of the highest honors a scientist can achieve.

In 2020, she is awarded the Darwin Medal by the International Coral Reef Society, which is given every four years to globally recognize a scientist for major scientific contributions throughout their career.

She holds this role until her retirement in 2020.

Knowlton diving in the Red Sea to retrieve an autonomous reef monitoring structure, or ARMS, as part of her work with the Census of Marine Life. She helped develop ARMS as a standardized way to gather specimens living near and on reefs. (Courtesy of Nancy Knowlton, photo by Michael Berumen)

Knowlton on PBS NewsHour in 2012 discussing the impact climate change has taken on the Great Barrier Reef in Australia.

Knowlton reflects that the biggest obstacles she faced throughout her career as a woman in science were covert issues like not being treated fairly. She feels fortunate that the overt obstacles that older women faced were gone by the time she started her doctorate in 1972.

The Sant Ocean Hall opens

The new Sant Ocean Hall exhibit opens at the National Museum of Natural History, for which Baldwin is head curator.

The Sant Ocean Hall is the National Museum of Natural History's largest exhibit, providing visitors with a unique and breathtaking introduction to the majesty of the ocean.

The Deep Reef Observation Project, or DROP, is founded

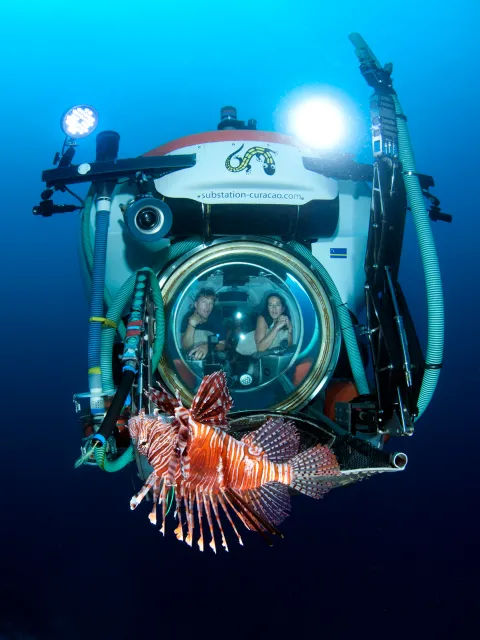

In 2011, Baldwin founds and begins directing the Deep Reef Observation Project. DROP is a research program that explores marine life and monitors changes in deep sea reefs in the southern Caribbean, which are around 1000 feet deep. The project works with scientists from NMNH, STRI, and the SMS.

Carole Baldwin inside of a submersible in Curacao, noticing a lionfish as part of research for DROP. (Courtesy of Carole Baldwin)

Baldwin “lionfish hunting." (Courtesy of Carole Baldwin)

A beaming Baldwin with her successful catch that can now be cataloged and used for scientific research. (Courtesy of Carole Baldwin)

An inside look at the work Carole Baldwin does at DROP.

Karen Osborn joins the Smithsonian as an Associate Curator of Invertebrate Zoology and Research Zoologist

Osborn researches the biodiversity found in the midwater and deep-sea, and helps draw attention to these fauna zones.

Osborn cites one of the biggest issues she faces as a woman in her field as the high service load of being the woman in the room. She founded the Inclusive Science Initiative to help combat workplace cultural problems like these.

Karen Osborn on an expedition to western Australia where she performed some fieldwork. (Courtesy of Karen Osborn)

A specimen of an ultra-black deep-sea fish, the Pacific blackdragon or Idiacanthus astrostomus, one of the blackest fish species ever recorded. Osborn and a team discovered how the skin of fish like these are covered in highly-pigmented granules that absorb up to 99.95% of all light that hits them. Osborn says imitating this strategy could help scientists develop more efficient ultra-black materials needed for things like cameras and camouflage. (Courtesy of Karen Osborn)

Osborn helped curate the exhibit “Life in One Cubic Foot” which opened at the National Museum of Natural History in 2016. Here are some of the organisms found in one cubic foot of midwater off California. (via Time)

Carol Baldwin becomes Department Chair of Vertebrate Zoology

In line with her interest in communication, in 2020, Baldwin is featured in a short film called At the Edge of Light, which focuses on some of the research she's done in Curaçao with DROP.

Baldwin feels fortunate that she hasn’t faced any hurdles throughout her career that were directed specifically at her because of her gender. The most difficult obstacle she faced because of her gender, though, was deciding if or when to have a family.

Ellen Strong achieves her highest position of Chair of the Department of Invertebrate Zoology

Strong discusses some of the research she focuses on as part of Smithsonian Science How.

Ellen Strong (center) with some of the mollusk collection. (via Colossal)

Strong with a specimen of Campanile symbolicum, or a "giant creeper" snail. Strong cites the specimen as one of her favorites among the collection. (Smithsonian Magazine)

The scientists discuss their experiences as women in the male-dominated fields of the ocean sciences

While women in science still face challenges, they continue to make significant strides, even since 2000.

The scientists talk of the crucial problems they think will continue to challenge women – like sexual harassment, microaggressions because of their gender, or if, and subsequently how, they will manage having a family. Also, most women in the marine sciences continue to be white, and so the next frontier will be to continue the fight for equality for women of all backgrounds.

Despite these issues, though, they are optimistic about the future: things are only getting better as time goes on and more barriers get broken.

Baldwin explains her belief that as time continues to pass, women will only see improvements in how they’re treated.

Parenti comments on the benefit of the different perspectives women bring to the table as more women achieve in science fields.

Knowlton says that there is a notable cultural shift in that women now know better than to put up with harassment. In light of the positive change she’s seen over her career, the problem has now shifted to include striving for equity for all identities, whether they are gender-based, race-based, religion-based, or otherwise.

The scientists offer advice to the young generation

First, follow your passions. Do what you love.

Second, be thoughtful about your career path. There is no formula for success – but be sure to put yourself in places that support you.

Third, you can do anything you want. And if you want to do science, it can be a ton of fun.

Osborn says to focus on what you’re passionate about and to find something that will excite you enough to get you out of bed with energy. If you love what you do, work won’t feel like work.

Parenti encourages young women to keep at it, and that there’s no one right way to achieve.

Knowlton loving her work as a graduate student in Discovery Bay, Jamaica in 1974. (via Restricted Waters)

Knowlton tells young women that they should be strategic about where they put their energy.

(Courtesy of Nancy Knowlton, photo by Bill Sacco)

Paul tells young women not to let anyone tell them that they can’t achieve what they want to, and that being a scientist can be incredibly rewarding – you are driven by curiosity all the time.

Baldwin encourages young women to get involved in science because it can be incredibly fun – it means being a treasure hunter! And, you can do anything you set your mind to.