Sea Sounds Embroidered in Silk

What does sound in the ocean look like?

For artist Lindsay Olson, the answer lies in the grain lines of silk, embroidery, beading and thread as she interprets amplitude waves and the unique sonic signatures of sounds heard in the deep ocean. Her intent is to capture the elegance and beauty of science through her richly stitched textile artwork.

Olson’s artwork series titled “Sound in the Sea” captures and makes tangible the invisible acoustics research conducted by oceanographers trying to understand how ocean life communicate and respond through sound. While for many the intricacies of acoustic data can seem abstract, displayed in stitches and embroidery they become a little easier to understand.

“Textiles are a good leveler, and a good invitation for people who are a little science-phobic,” said Olson. “It’s a way to make the subject a little more comfortable.”

For an artist trained in the fine arts and fashion, textiles became a science communication tool. Olson understands the barriers some people face when it comes to understanding scientific concepts. For much of her life she was a self-proclaimed science avoider, but a canoeing trip as an adult changed that perception.

Upon paddling towards a man-made waterfall, Olson was struck by its beauty. She later learned the waterfall was a SEPA station, one of the final steps in wastewater treatment. Fascinated by the path and movement of water, she traveled to the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Chicago, the world’s largest wastewater treatment plant, and interviewed the scientists and workers.

“I fell in love with science in that wastewater treatment plant,” said Olson.

It was through her experiences working with engineers, operators, and microbiologists in a real-world environment that led Olson to switch her artistic focus to portray science. The first artist in residence at Fermi National Laboratory, she worked to reveal the world of subatomic particles. But while she explored the realm of particle physics, she continued to be drawn to the beauty of water. When offered the opportunity to join a group of scientists on a three-week research expedition, she jumped at the chance. Dr. Jennifer Miksis-Olds, a scientist and art lover, was the principal investigator for the Atlantic Deepwater Ecosystem Observatory Network. Miksis-Olds was keen to have an artist aboard her research cruise to help distill the science and communicate its findings to a broader audience.

Aboard a large research vessel in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean in 2018, Olson was both working as an artist and thrust into the daily life of a marine scientist. High research costs aboard a ship mean every able body was put to work collecting data during the precious time at sea. Olson was no exception. She meticulously recorded latitude and longitude coordinates, processed water samples, and other duties on the science crew, all while imagining the stitches she would sew and scribbling those ideas in a sketchbook.

“It was a consciousness-expanding experience. It is one thing to be told the ocean is very large, and it’s quite another to feel like an infinitesimal spec in the middle of a cosmic ocean,” said Olson. “I had a similar feeling that astronauts must feel looking down on Earth from outer space.”

Living and working with the scientists also meant Olson became immersed in the science, and working closely with Miksis-Olds, an acoustician, meant learning the basics of ocean acoustics. She diligently worked to understand the difference between passive acoustics, the study of sound in an environment with the use of an underwater microphone called a hydrophone, and active acoustics, the study of an environment using echosounders. In active acoustics an echosounder emits a very short pulse of sound and then records the echoes that reflect off of small animals (zooplankton) in the water column. Both methods would inspire Olson to create large sized embroideries.

The acoustics research conducted by Miksis-Olds aims to understand the natural soundscape of the ocean by listening and recording the sound of the ocean with a hydrophone. A hydrophone can pick up the sounds of clicking dolphins, the rumble of a distant earthquake, or the pincer clicks of snapping shrimp. The sound waves are then recorded and plotted according to their frequency over time as data points on a graph. The drone of a ship will appear as a short and monotonous pattern, while a whale song will sharply dip and peak in a melodious combination. Collectively, the sounds shape our understanding of the underwater world and give researchers a window into how animals communicate and navigate in the vast seascape. As humans continue to develop the ocean through shipping, aquaculture, mining, and other construction, the natural sounds of the ocean can be drowned out by the noisy activity.

Armed with the knowledge learned from weeks at sea, rolls of silk, thread, sequins, and a needle, Olson transformed the world of ocean acoustics onto large scale embroideries. Inspired by large textile work by Lizzie Funk, she created two pieces that relied on sewing and embroidery skills to convey scientific concepts. Silk dupioni, a special type of silk known of its iridescent luster, was chosen for its grain lines that are reminiscent of ocean waves, and blue colored thread for the hues of water.

“Circular Sounds” takes the passive acoustics graph data and displays them in embroidery and beading. The sounds of marine mammals, fish, seismic events, and shipping are weaved together, showing that the ocean soundscape is now a soundscape of both nature and human activity. At the center, a stitched equation used to describe sound waves incorporates the mathematical side of science. And the inclusion of a chemical reaction around the periphery is a nod to ocean acidification—as the ocean becomes more acidic due to climate change the ocean soundscape will likely change in ways unknown to science.

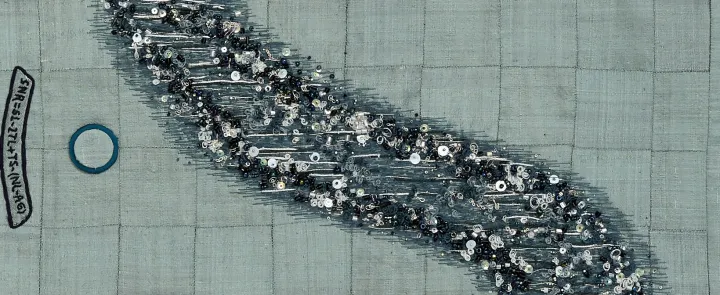

“Rhythmic Seas” represents the other side of acoustic science, the active acoustics research. Scientists use reflecting soundwaves to help illuminate the daily migration of zooplankton from deep in the ocean up to the ocean surface. A ping of sound is sent into the ocean from the ship, it then bounces off of any object in the water and returns to a receiver. Scientists can “see” the mass of millions of zooplankton on a monitor screen, a visual created by a computer. Olson shows this on silk. Dark blue thread and shimmering sequins represent the mass of bodies as they migrate to the surface. Embroidered equations that describe how sound behaves when they bounce off of an object arc in aqua thread to form a ping. At the bottom of the tapestry a blanket of shimmering white sequins represents “marine snow”—the carcasses of dead zooplankton that drift to the bottom of the sea.

Together, “Circular Sounds” and “Rhythmic Seas” act as a window into the world of ocean acoustics, one that illuminates a dark and mysterious ocean ecosystem.

Olson considers herself to be an ambassador for both the science the artwork communicates and her profession as an artist. One of the most rewarding parts of her projects are the many opportunities she has had to share the work with the general public. Scientists too appreciate the scientific accuracy and beauty of her work.

“I’ve had scientists tell me that this is the first time they’ve ever felt connected to a piece of art, and that is really powerful,” said Olson.

Perhaps art is the ultimate connector, creating emotion and a bond where there seemingly is none. Data can be numbers on a spreadsheet, or they can be a beaded silk that makes people stop dead in their tracks. They can seem daunting or out of reach, or displayed in a way that gives pause and contemplation. In a world where science and art are often at opposite ends of the spectrum, the unification of the two shows we can all revel in the wonders of our universe. Thankfully, Olson is a willing translator, taking the time to learn complicated subjects and then distill them into beautiful artwork for everyone to enjoy.

_______________________________________________________________

Editor’s Note: Lindsay Olson will be on site at the National Museum of Natural History on June 8, 2023 for the World Ocean Day celebration.