Joan Murrell Owens and her Button Corals

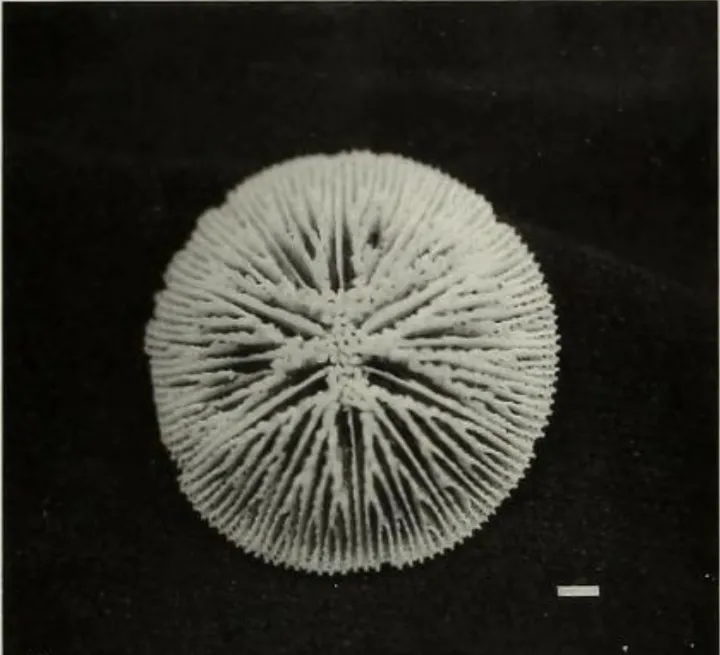

In the 1950s it was unheard of for a young Black woman to become a marine biologist. That didn’t deter Joan Murrell Owens. As a child she read stories about Eugenie Clark, the shark lady depicted in her books, and decided that she too would study the sea. Where Clark had her sharks, Owens would have her button corals—small snowflake-like creatures that lived deep in the sea. These snowflake corals, however, were housed in the drawers of the Smithsonian’s collections, and Owens would become a meticulous cartographer, detailing every groove and branch of their skeletons through the microscope lens. It was that discipline and determination that led her to become the first Black woman marine biologist, geologist, and paleontologist.

As a young girl Owens was enamored by the ocean. Her father, William Murrell, a dentist, served as her role model and teacher, taking her and her siblings on weekend fishing trips and inspiring them to pursue careers through higher education. Both her parents, all her aunts and uncles, her sisters, and all her cousins were college educated, a rarity in the early 1900s. Inspired by books by Jacques Cousteau and Eugenie Clark, Owens’ goal in life was to become a marine biologist, but opportunities for Black women at the time were limited. Fisk University, the historically Black university Owens attended, did not offer a biology degree. Instead, she attended as an art major, considered a more suitable degree for women at the time.

Owens would continue her education at the University of Michigan where she received a master’s in guidance counseling with an emphasis in reading therapy. For the next decade Owens worked in education teaching remedial English at Howard University and then as a curriculum creator for the Institute for Services in Education in Newton, Massachusetts. Despite a successful career in education, Owens still held onto the dream of becoming a marine biologist.

While in Massachusetts Owens became disenchanted with her career. Her position at the Institute for Services in Education slowly began to change to a point where she was overseeing more advanced material, and she felt to continue would require more schooling. Then she discovered that her male colleagues were being paid more than her, the final straw needed to push her back into the career she coveted. With guidance and support from a colleague at MIT, Owens applied to George Washington University to pursue her passion for the ocean.

At the age of 37, Owens began her new career. She started from square one, in a bachelor’s program of geology with a focus on paleontology and zoology. Still financially on her own, she relied upon a museum technician job at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History where she catalogued the paleontology department’s specimens. Nearly two decades after she first went to college, Owens found that her race and gender were no longer barriers to her success. Though some of her peers experienced resistance from mentors, Owens was lucky to find support both in the geology department and at the Smithsonian. It was this experience that helped her to receive both a master’s degree and a PhD.

But her path still wasn’t free of obstacles. Often, marine biology positions required some experience and willingness to dive. Owens had sickle cell anemia, a genetic disease that limited the amount of oxygen in her blood, and a diagnosis that effectively dashed all dreams of diving. Thankfully, her relationship with Stephen Cairns at the Smithsonian allowed her to continue marine research through the study of collection items.

“She was a gentle person, a very receptive person to learning and direction. She was very curious, and she had a great drive to get a PhD,” says Stephen Cairns, coral biologist at the Smithsonian and mentor to Owens.

For her PhD thesis and later as a professor at Howard University, Owens studied button corals from the 1880 Albatross collection. She built upon the work by Don Squires, a prominent coral biologist at the Smithsonian who disappeared from work one day and left all his possessions behind. Using his manuscript as an initial blueprint, she meticulously catalogued the physical properties of each button coral in the collection. These corals were small, about the size of a quarter and very delicate. Examination required a process called thin sectioning where a sliver of the coral was cut to a width of only a few microns. “If you hold up a skeleton to the light you can see through them, unlike a reef coral that is hard as a rock,” explains Cairns.

By the end of her time at the Smithsonian Owen’s would discover a new genus of button coral—the Rhombopsammia— along with three new species, which she named after a snowflake, Squires, and her husband. She also published a hypothesis for why these deep-sea corals were mobile, unlike the majority of shallow water corals. She proposed that shallow water free-living mobile corals in the Cretaceous period migrated into deeper water. Then, since they were in deep water and couldn’t get enough calcium carbonate for their skeletons, they maintained a lightweight body that enabled movement.

“It’s important because of its contributions to our understanding of the life of the sea and some of the ways in which ecology and evolution interact. Also, it is important to others working with deep-water organisms because of some of the relationships I think I indicated—if not proved—between water depth and availability of calcium carbonate that influenced the physical evolution of some organisms,” said Joan Murrell Owens in an interview with Wini Warren in 1996.

Despite her academic achievement, Owens found her greatest joy in her students. A professor at Howard University, Owens spent the academic year teaching and the summer months furthering her research. She was the only woman in the geology department, and many of her students had never met a woman teacher before, never mind a woman scientist. Her legacy is one of breaking barriers and enabling others to follow in her wake. Sadly, Owens passed away in 2011 at the age of 77, but she will forever be known as the marine biologist with the beautiful button corals.