Circumnavigating our Changing Oceans

In a time of environmental uncertainty, the Polynesian Voyaging Society draws strength from their past, plotting a course to circle the Pacific Ocean and inspire a new generation of navigators.

How do you find an island you can't see? Before GPS or even the compass, Polynesians navigated voyages through vast, open ocean without instruments. This practice, in which crew members relied on their observations of celestial bodies, ocean currents, and other patterns within nature to orient themselves at sea, was known as wayfinding. Since the first instances of western contact and colonial occupation, the pressures of assimilation whittled away Polynesians’ knowledge of their own wayfinding practices. The traditional methods of navigation passed along through oral history were all but lost. Then came Hōkūleʻa.

Hōkūleʻa (named for the star Arcturus) is a performance-accurate wa'a kaulua, or double-hulled voyaging canoe, best known for her 1976 voyage from Hawaii to Tahiti. When Hōkūleʻa was first launched in 1975, she heralded a Hawaiian cultural renaissance, and at the time of the canoe’s maiden voyage, Future Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS) crew member Billy Richards didn’t anticipate setting sail with her. There’s a phrase for what he felt when he first saw the canoe—conceived of and built by Indigenous Hawaiian artist-historian Herb Kane and anthropologist Ben Finney—where she rocked at anchor in the chest-deep waters of Honolua Bay, Maui. He felt “Haka Ka’au.” It means, “being in the same place as our ancestors, just at a different time,” Richards shared—not in the past, but in the same space of it.

“We, as a Hawaiian people, were trying to find out where we came from, so as to rediscover ourselves,” Richards described. “We had lost so much of who we were.” He visualizes their lineage as a great mo’o (lizard) clinging to the heavens: the forelegs the current generation reaching to the future, the back legs their elders supporting them, and the long tail the unbroken line of ancestors. Generations ago that tail fell off. On March 8, 1976, Richards explains, that tail began to grow back. Now, thanks to the efforts of PVS and the larger voyaging community to preserve and perpetuate wayfinding practices, that connection continues to strengthen.

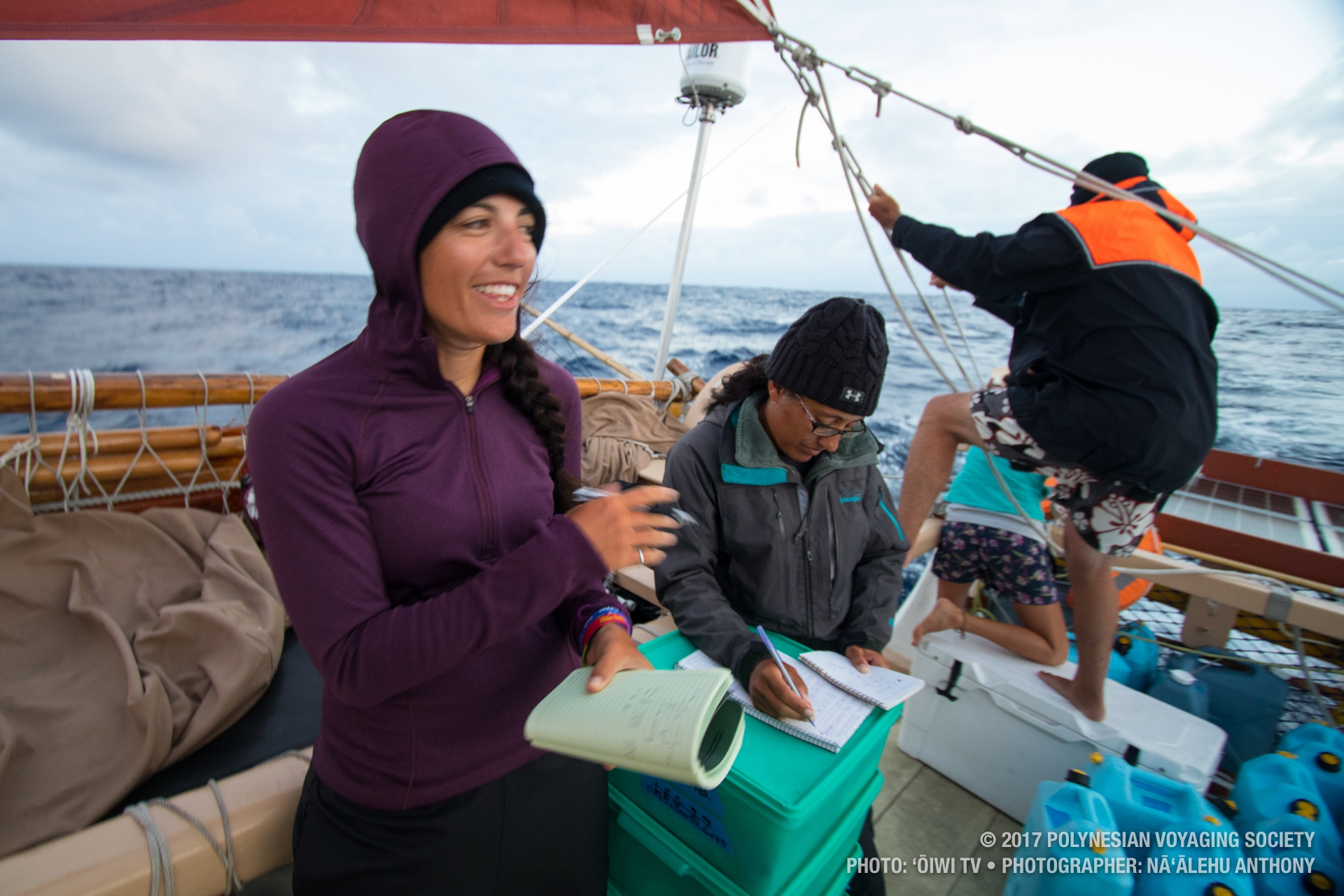

When current Voyaging Director Lehua Kamalu and her fellow crew headed toward Rapa Nui (also known as Easter Island) aboard Hōkūleʻa in 2017, they planned on relying on wayfinding methods but also on the insights of their mentor, Nainoa Thompson. Thompson was the president of the society and a master navigator of modern long distance ocean voyaging. What they weren't anticipating was a sudden change of plans; personal matters kept Thompson ashore, forcing the crew to complete their first voyage "left to their own devices," as Kamalu put it.

While they had what it took, some of them had yet to be convinced. "You start to question whether you know what you're doing pretty quickly," Kamalu laughed. "A lot of the navigators who had trained before us would say that at some point you have to let go of what you think you know, and push out of your comfort zones."

It's said that a navigator would be trained from the age of two, but they were already adults; and, fluent in the language of physics, formulas and vectors, the crew had yet to get the hang of embracing their intuition. Almost two weeks in, they had followed their sail plan to the letter and still hadn’t found the island.

At the end of their rope, they learned to let go of their pre-plotted sail plan long enough to process what their sensory observations were telling them. Finding Rapa Nui would require locating the signs of an island without seeing the landmass itself—searching for the types of cloud formations that typically cluster over land, or reading the direction of the wind and the pulse of the ecosystem around them, such as the presence of wave patterns or reef fish that indicate a nearby shore. When Rapa Nui finally emerged on the horizon, they could hardly believe their eyes.

"According to our calculations, we would've never found the island," Lehua reflected. But when they started to trust in the wayfinding skills Nainoa Thompson and other PVS mentors had shown them, the course became clearer. "It makes you wonder what other signs are out there in the natural world that you aren't aware of. You realize you really don't have it all figured out."

According to Kamalu, the true navigator only knows that they don't know anything. It’s a discipline that offers no absolutes, only “humble attempts to read what nature is showing us.” That openness is where the magic happens, and the Polynesian Voyaging Society aims to share this same spirit of exploration with a wider audience.

Moananuiākea, a word referring to the Pacific Ocean and all it connects, is the name of PVS’s next endeavor to strengthen those connections— and its most ambitious undertaking yet. PVS has been planning the Moananuiākea Voyage for three years. Venturing forth from the organization's home island of Hawai`i, the 42-month journey will circumnavigate the Pacific, traveling 41,000 miles and visiting 345 ports, 46 countries and archipelagoes, and 100 indigenous territories. Kamalu—who by 2018 had become the first woman to lead-captain a long-distance voyage when she navigated Hikianalia on a 2,800-mile journey from Hawai`i to California—is the Voyaging Director for this next adventure.

Originally intended to embark in 2020, but rescheduled to spring of 2023, Hōkūleʻa has found herself in a holding pattern since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Though the traditional canoe and her modernized safety escort Hikianalia will not set sail until permissions to visit are secured and travel is safe for all involved, preparations continue as scheduled; and there's a leg of the journey that will launch regardless. It's called Wa`a Honua (Canoe for the Earth), and its deck will have enough room for all of those who Moananuiākea can't reach in person.

This third “canoe” takes the shape of a virtual platform designed to connect audiences the world over with accessible participation in exploration, research, and lesson plans relating to the voyage. Once live, you’ll be able to visit it from any web browser to find educational content, blog entries, and live streams with crew and guest speakers discussing a range of topics connected to the voyage—like community leadership, climate change, sustainability, and cultural and environmental preservation.

“We’re using our platform to inspire people to respect and connect with what’s around them,” explained Sonja Swenson Rogers, the communications director for PVS. “As people follow our voyages and hear the stories shared from the canoe, the hope is that it encourages them to seek out ways to help steward a thriving, sustainable world.”

As Hōkūleʻa and her sister canoe Hikianalia gear up to tackle their latest circumnavigation of the globe, the crew are well acquainted with the legacy they’re carrying and the power it has to inspire better community and environmental stewardship. Today, the canoes have a variety of backgrounds and identities represented on deck. “We know who we were as a people. Now it’s about all of us. If you live on an island, you understand the interconnectivity of all things,” Richards explained. “You understand the limited resources. You understand that all of Earth is an island, and that you can only use and lose so much.”

With the wind in its sails and the world watching, the Moananuiākea voyage will steer that point home. In striking capital letters, the voyage’s home webpage signals its mission: "THE ISLAND WE SEEK IS THE EARTH OF TOMORROW." The Earth of tomorrow may not be visible to us yet, but Moananuiākea stands as proof of its potential, and a testament to ours—there is a navigator in all of us.