Dr. Marian Pettibone, A Woman of Firsts

Sixty years ago, when women more commonly assumed roles as secretaries or homemakers, Dr. Marian Pettibone was breaking barriers in the vast halls of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. She did so by studying worms and became an eminent scientist in her field when women in science were rare.

“Marian worked during a time when being a female scientist was even harder than today, and she made it to one of the most sought-after positions in the country. If you were a curator in Washington, you’d just about died and gone to heaven, especially if you were a taxonomist,” noted Kevin Eckelbarger, Director of the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center and a former advisee of Pettibone’s in the early 1970s.

As the first woman to rise to the status of Curator in the Department of Invertebrate Zoology at the National Museum of Natural History in 1963, Pettibone held the vital role of collecting and preserving organisms at the museum to build a record of life on our planet. She was an expert in identifying and classifying marine segmented worms, or polychaetes, an extremely diverse and prolific group of marine invertebrates with many unique adaptations. This experience made her the perfect candidate to become the first-ever Curator of Polychaetes for the museum.Her career took her around the world on research expeditions to places women of the time wouldn’t dream of visiting, all to collect organisms that would help uncover the evolutionary history of the worms she dedicated her life to. Pettibone discovered and described an astounding 143 new species, published 84 scientific papers, one world-renowned book, and collected thousands of organisms for the museum. Her climb to such an esteemed position required tenacity and determination.

Pettibone’s Life and Early Career

Pettibone, the fourth of six children, grew up in a large family led by a “fire and brimstone” Baptist minister dauntingly referred to as “The Reverend” by her nephew, Ned Swanson. Born in Spokane, Washington, she spent her formative years near the invertebrate-rich waters of the Pacific Northwest. Her exposure to large, predatory polychaetes with projectile jaws and beautiful feather duster worms common in the Puget Sound may very well have inspired her later career.

In 1930, Pettibone received her Bachelor of Science degree from Linfield College. Two years later, she completed her master’s degree at Oregon State University under the tutelage of Dr. Rosalind Wulzen, a prominent female physiologist of the time.

For the next seven years, she taught biology at an all-girl boarding school, St. Helen's Hall Junior College, in Portland, Oregon. During this time, World War II broke out, and everyone was called to serve in the war effort. Dr. Pettibone joined the wartime workforce, but, fitting her uniquely driven character, she did so in an unconventional way:

“While standing in line to work as a typist for the war effort, she [overheard] that the men standing in the next line over were going to get paid a lot more than the typists. She switched lines and became a spot-welder on the victory ships being produced at the shipyards in Tacoma. She quickly rose through the ranks to become a quality inspector for spot-welding at the shipyard,” — Kristian Fauchald, 2nd Curator of Polychaetes, NMNH.

After the war, Pettibone built her career at several universities, first at the University of Washington while pursuing her Ph.D. in zoology, then as a research associate at the Johns Hopkins University Office of Naval Research, an instructor at the Marine Biological Laboratory, in Woods Hole, MA, and as a faculty member of the University of New Hampshire. In New Hampshire, she published her widely renowned book, “Marine Polychaete Worms of the New England Region.” Colleagues from across the world wrote to her frequently asking when she would publish a second volume.

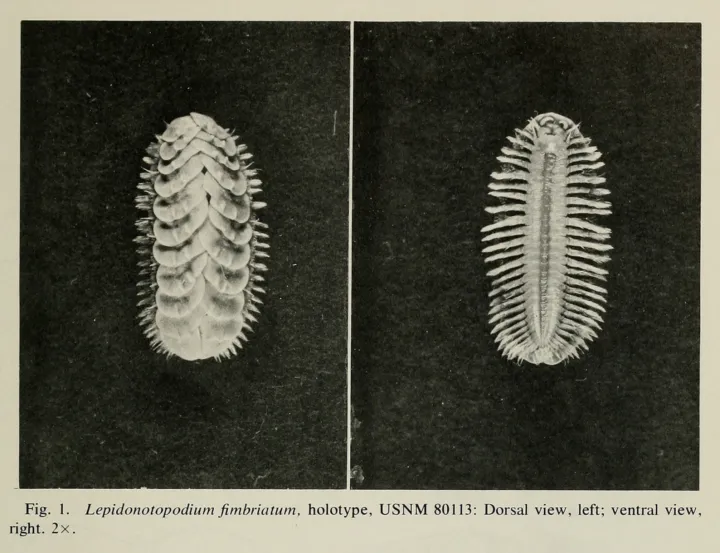

In her research, she explored her passion for polychaetes, cultivating a particular interest in scale worms (Polynoidae), one of the most diverse families of these marine segmented worms. Scale worms are found throughout the entire ocean, from the icy Antarctic to tropical waters and beyond, and are masters at adapting to their environments. Uncovering their evolutionary relationships is still a difficult task, even with modern technology.

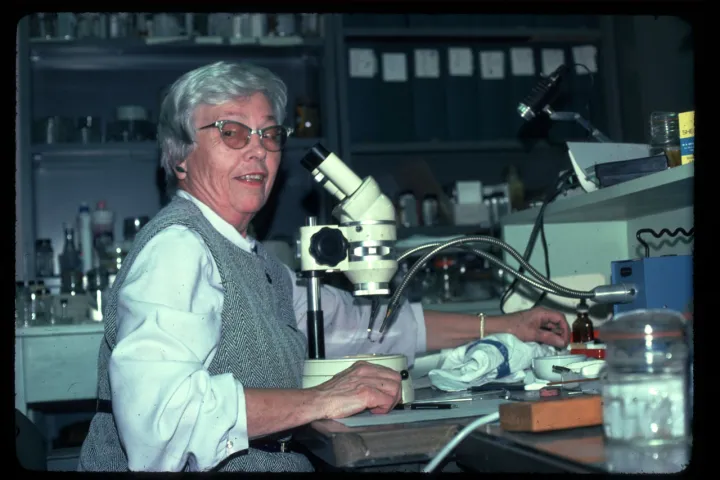

Pettibone used light microscopes to conduct a meticulous inspection of anatomy, comparing features like the number of segments, number, shape and decorations on scales, forms of various head appendages, and types of bristles to differentiate species and determine how they were related. She took detailed notes and drew just about everything she examined, skills that she cultivated in her students. Through studying the anatomy, behavior, and ecology of these animals, Pettibone was able to classify them - organizing them into hierarchical, relational groups from animal kingdom all the way to species.

What better place to utilize these skills than at the place where animals were sent from across the globe for identification and classification: the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH).

Her Research at NMNH

By the time she arrived at the Smithsonian in 1963, Pettibone had already described 17 new species and made important revisions to our understanding of the evolutionary relationships between polychaete groups. As Curator of Polychaetes, she examined a great diversity of bizarre new species that poured in from shallow to deep waters all around the world. Her interest in scale worms, paired with her keen eye for detail, helped to firmly establish Pettibone as the world expert on this group of armored annelids. After 15 years as Curator at the museum, she was perfectly poised to capitalize on a groundbreaking discovery that was about to emerge from the deep sea.

In the late-1970s, biologists discovered an alien ecosystem growing around underwater chimneys spewing magma-heated, mineral-rich seawater while exploring the boundaries of tectonic plates in the Galapagos. These hydrothermal vent ecosystems were crawling with polychaetes, including scale worms, unlike any seen before.

Vent ecosystems occur much deeper than sunlight can penetrate, reach temperatures of over 700 degrees Fahrenheit, and produce poisonous substances like sulfur, making life challenging, to say the least. These extreme conditions lead to extreme adaptations and unique associations between organisms. Around hydrothermal vents, bacteria use the poisonous sulfur compounds in the superheated vent waters for energy. Animals, in turn, cultivate or host these bacteria to harvest that energy and survive in this toughest of habitats. You would think these habitats would be sparse, but they are literally crawling with life, and polychaetes dominate many of these vent systems.

As the world expert on marine segmented worms, “Marian started receiving shipments of really bizarre looking worms from the vents,” recounted Dave Pawson, Curator of Echinoderms (sea stars, urchins, and the like) during Pettibone’s tenure. The creatures coming out of the vent ecosystems were so unique that Pettibone had to establish several new families and genera to place the many new species she discovered on the tree of life. Her involvement in documenting the amazing array of animals found at hydrothermal vents was a definitive moment in an already esteemed career.

A Legacy

After 15 years as Curator at the museum, Pettibone was required to retire at the age of 65 due to a federal workforce rule at the time. That didn’t keep her from the museum. Despite official retirement, Pettibone continued to spend 10 or more hours a day working there, even on weekends, documenting and categorizing worms in the collections. When she died in 2003, she was in the middle of describing many new species and left behind over 100 organisms she had identified as new to science, awaiting description. Those specimens are now in the hands of the next generation of scientists.

Today, a team of scientists in the Department of Invertebrate Zoology is taking Pettibone’s collections into the 21st century. By using micro-CT technology to scan the over 150 “type” specimens (specimens that are the first of their kind to be collected and named) collected by Pettibone, the team will create virtual models that anyone with access to a computer can examine. “Micro-CTs provide a way to study anatomy in more detail than we ever dreamt possible. Even better, unlike genetics or several other imaging techniques, we can do it with valuable museum specimens like those from the Pettibone collection without damaging them,” says current Curator of Polychaetes, Karen Osborn. These types act as essential records for comparison as other worms are discovered in the ocean.

Thanks to Dr. Pettibone’s efforts, our understanding of polychaete evolution has been forever changed. Her story and research continue to inspire future generations, and the new effort to democratize Pettibone’s polychaete collections will increase opportunities for young scientists around the world. She uncovered creatures from some of the most remote places in the world and gave names to the diverse worms along our own shores. The countless hours Pettibone spent at her microscope broadened our understanding of the diversity of life on our planet and opened doors for others to join in the discovery for decades to come.