Kako Morita: Bridging Art and Science Through Natural History Illustrations

Housed within the renowned Division of Fishes at the National Museum of Natural History lies a staggering collection of over six million specimens. While the majority are preserved in jars of alcohol, a remarkable subset of more than 30,000 objects are not actually fish— they are a vibrant array of illustrations, including intricate line drawings, delicate watercolors, and captivating paintings.

In 1963, while sorting through filing cabinets, Victor G. Springer, then Assistant Curator in the Division of Fishes, came across an unusual illustration that captured his attention.

This image featured Ebisu, well-known in Japan as the god of fishermen and luck. In this illustration, he is depicted holding a large fish, a fishing pole, and is dressed in a noble kimono robe. This drawing sparked the beginning of Springer’s fascination with its artist, Kako Morita.

Though Victor Springer’s original interest and research in Morita began decades ago, a recent study published by Smithsonian researchers Ai Nonaka, Lisa Palmer, and Laurence J. Dorr further explores Morita’s life, artwork, and how he navigated his career across the United States in the early 20th century.

Morita was a Japanese artist and a scientific illustrator who arrived in the U.S. around 1902. While much of his biographical information remains unknown, the authors were able to uncover significant details about his travels between Japan and the United States, as well as his affiliations with various organizations and biologists during his time in America.

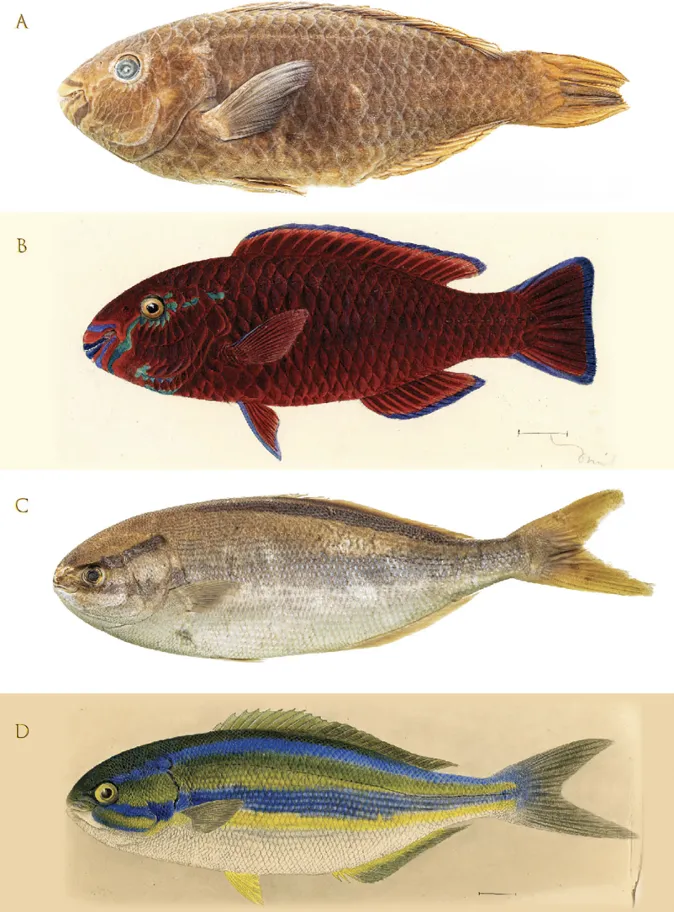

Arguably Morita’s best-known work, scientific illustrations of fish were made at Stanford University in 1902-1903. Here, he worked as an assistant artist for David Starr Jordan, a prominent American fish biologist and the first president of Stanford. Discovering correspondence from Morita to Jordan throughout his time in the United States not only allowed researchers to track Morita’s footsteps, but also gave insights into their strong relationship and how Jordan’s continuous support helped Morita find work as a scientific illustrator.

Morita’s time at Stanford is considered the most productive period of his career. The illustrations he created from 1902-1903 were featured in publications on Japanese, Hawaiian, and Samoan fish, including The Fishes of Samoa (Jordan and Seale, 1906), which was published by the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries.

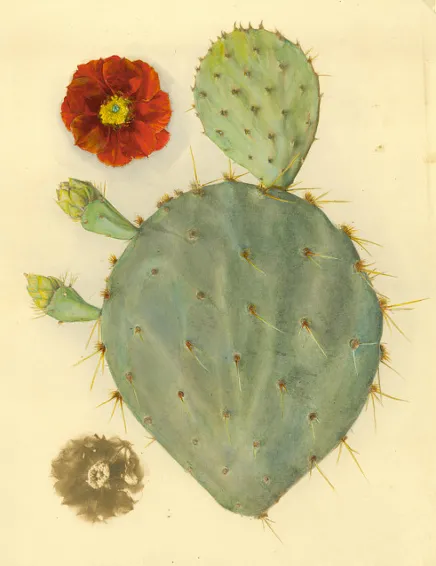

After leaving Stanford, Morita continued his work in scientific illustration from 1904 until 1918.During this period, he worked in various locations including Minneapolis, Chicago, the Dry Tortugas (Florida), and Washington, D.C.. He expanded his focus to illustrate other groups of organisms, such as birds, plants, mammals, and invertebrates, where he completed work for some of the most renowned scientific institutions, including the American Museum of Natural History, the Carnegie Institution, and the Bureau of Biological Survey (now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). After 1918, researchers lose track of his activity until about twelve years later.

The last written records of Morita date back to 1930, when he was denied entry into the United States. Although Morita traveled extensively throughout his time in the states and built an impressive list of scientists and organizations that he worked with, researchers believe he was constantly in search of his next opportunity and struggled to make a living as a natural history illustrator.

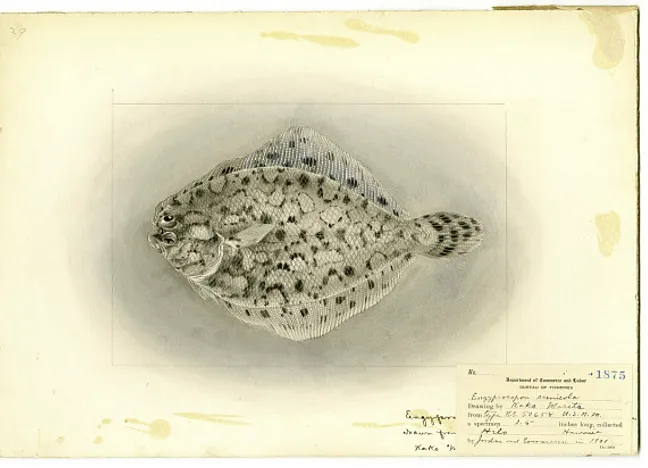

For more than 100 years, the largest collection of Morita’s fish illustrations has been stored and managed within the National Museum of Natural History. Here, the Division of Fishes is home to 97 paintings and drawings– both in color and black and white– which depict a total of 95 different fish species. Not only is his work visually stunning, but it also serves as a crucial contribution to ichthyology, the scientific study of fish.

Scientific illustrations, while useful on their own, can also complement another type of collection item often used in research– preserved specimens. Alcohol-preserved specimens enable the long-term storage and protection of entire organisms, including their soft tissues and even gut contents. While many important features are conserved in these specimens, one key characteristic is often lost– color. This is where scientific illustrations prove essential, allowing these two distinct types of collection items to enhance the other. Illustrations are able to capture details like color that may have been visible when the species was first discovered but have faded over time in the specimen. By combining the strengths of both, scientists gain a more complete understanding than they would from either illustration or preserved specimens alone.

Scientific illustrations were also an incredibly important way to document newly discovered or described animal species before the invention of photography and modern imaging technologies. These hand-drawn illustrations served as the primary method for capturing the intricate details of specimens, providing a visual representation of their distinctive features. For thousands of years, in a time when photographs were not available to scientists, illustrations were the sole means to record and communicate the appearance of species and their anatomy.

Even in today’s world, where cameras and high-tech imaging tools are readily available, scientific illustrations remain a vital component of communication in science. While photography and digital imaging capture details of the natural world with great precision, illustrations continue to be invaluable for conveying complex concepts, intricate details, and abstract subjects in a way that is engaging, accessible, and easy to understand.

Morita and countless other scientific illustrators have demonstrated that science and art are not opposing forces, but rather complementary fields that enrich each other, offering invaluable contributions to both historical and scientific knowledge. Through their work, scientific illustrators illuminate the unseen– whether it is the intricate details of fish anatomy, the vastness of the universe, or the recreation of extinct species. As for Morita, his work continues to reveal in color a past world that might have otherwise been forgotten.