Navigating the Waters with Micronesian Stick Charts

When islands and atolls only rise a few feet above sea level, it is difficult to get from place to place without learning the ways of the sea. The Marshall Islands—a sprinkling of islands and atolls in the North Pacific—have been inhabited for around 3,000 years with small communities where Marshallese people cultivated crops and fished on the surrounding reefs. They relied on their knowledge and relationship with the sea for most things—food, transportation, and social interactions.

Centuries ago, the Marshallese were able to create effective vessels, known as outrigger canoes, and develop their own system of piloting and navigation. Long before the time of modern mapping and GPS, the Micronesian people began to rely on their ability to sense the motion of the waves for navigation purposes. Thus, stick charts were born.

Their stick charts, however, were not really made of sticks, and not really used for navigation. We can’t help but be intrigued by their misleading names and intricate designs. Made from coconut strips, palm strips, and cowrie shells, navigation charts are thought to visualize the secret knowledge navigators, known as ri-metos, held. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History currently holds 15 of these stick charts in their collections. Although the charts are difficult to interpret, often only able to be read by the creator, thorough investigations of these Micronesian artifacts by anthropologists have lent a general understanding to the abstract representations of currents, wave and wind patterns, and marked locations of atolls and islands.

Anthropologists work with collections objects that may initially be difficult to decipher but are very much worth maintaining and learning from. Our understanding of these charts has uncovered that there are two different types—meddo and mattang. Meddo are closer to what we would think of as maps, while mattang are more like scientific models of ocean phenomena. These two different types of charts are key to understanding the Micronesian’s knowledge of the sea.

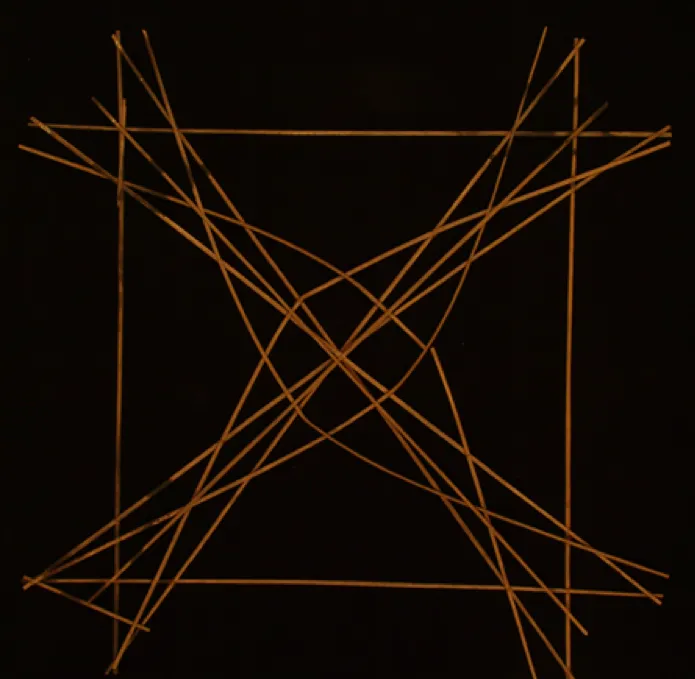

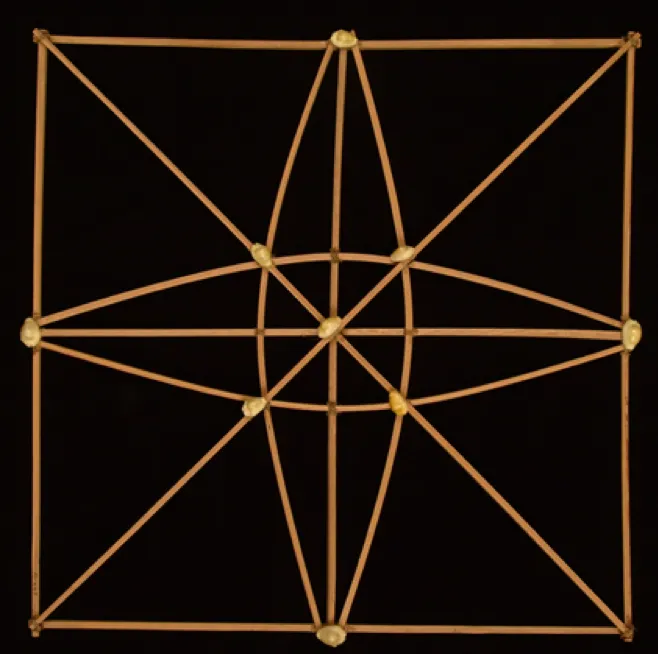

Mattang are thought to depict swell movements, wind patterns, and wave interactions that occur around a single atoll or island. Curved strips likely indicate the direction of ocean swells when deflected by the presence of land. Where these curved strips intersect with one another represent confused, or highly disturbed, seas. Confused seas were important locations to understand as they were often a valuable indicator of the whereabouts of the navigator.

For the Marshallese, mattang were training tools that abstractly illustrated general concepts of ocean movement and other wave actions such as reflection, the change of direction of waves when they bounce off of a barrier, and refraction, the change of wave direction when passing over different depths or substrates. The Marshallese understanding of these physical characteristics of the ocean came solely from observation and experiences at sea. The knowledge was passed down not only through the charts, but from one generation of ri-meto to the next.

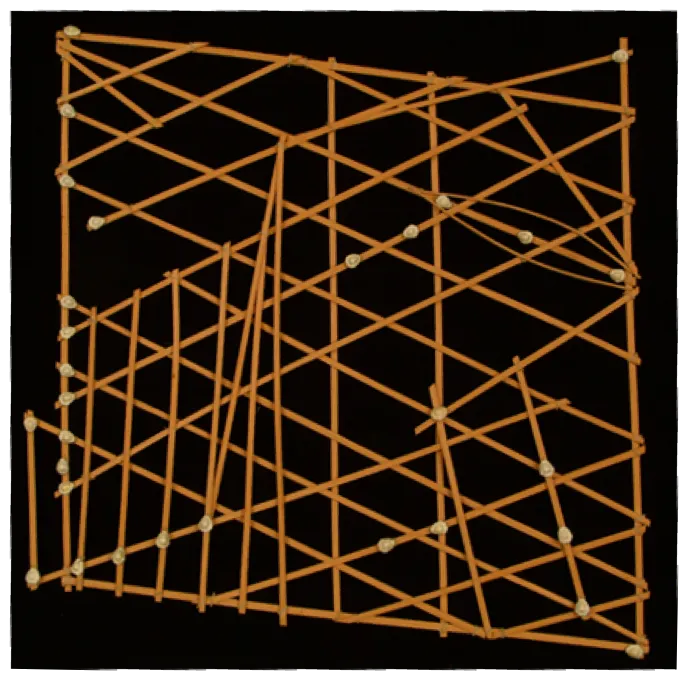

In contrast, the meddo is a chart that was used for piloting instructions. Ri-metos were thought to keep mental maps gained through their experiences at sea that lent to their understanding of these charts. Each cowrie shell represents an island or atoll and the arranged sticks depict potential navigation courses between them. Currents are represented by short, straight strips while longer strips may be an indicator of the direction of certain islands. Although the positioning of islands relative to one another turned out to be quite accurate, these charts were not to scale, meaning that distances are not exact.

As they weren’t literal maps and quite fragile, charts like meddo and mattang were not even brought along on journeys. Instead, ri-metos memorized their contents prior to a voyage. While these charts may have helped on land, ancient navigators relied on the art of wave-piloting once they were out at sea.

Using the sophisticated art of wave-piloting, ri-metos relied solely on the feeling of the ocean to navigate. Leaving the charts behind and relying on knowledge and instinct alone, the Marshallese were incredibly precise navigators. They were able to read the sea by feel and sight to determine which direction they were going, where the nearest land was, and what direction they wanted to continue in.

There was a time when scientists and scholars doubted the accuracy of Marshallese navigation. Researchers have since found that the navigational techniques of this pre-literate civilization align quite closely with oceanic phenomena that we have come to understand today. Unfortunately, due to several cultural shifts and external factors, much of the navigation knowledge in the Micronesian culture has been lost.

While the practical importance of these charts may be essentially lost, the cultural importance remains alive with the Marshallese people and within the Smithsonian’s collection. These Micronesian artifacts provide insight into how humans have adapted to life surrounded by the sea in the past. With sea level on the rise, understanding these adaptations and ways of life may be of increasing importance in the Pacific islands and beyond.