Nimble Fingers: the Women Behind Maine’s Canneries

In Maine lobster is king. The bug-eyed crustacean is an emblem of the state, with people lining up in the summertime for a taste of the sweet meat at the local lobster shack. Maine harbors are dotted with moored lobster boats, and the industry employs over 35,000 people in the state. Not too long ago, however, the Maine seafood industry had another staple vying for the top spot—sardines. At the height of the sardine industry in the early 1900s Maine supported 89 canneries, and the industry employed over 8,000 people. In towns up and down the coast, morning routines included the blast of the cannery whistle calling employees to work for the day. At the heart of the operation were the packers, nimble fingered women who sliced the fish with cutting shears and filled tins.

Women are often an invisible force in the fishing industry. Today, visions of hardened, bearded men come to mind at the mention of fishermen, and too often women are forgotten, or their roles deemed unimportant. Throughout history, however, women have been present, often as the physical harvesters of fish and other seafood. In Iceland, recent historical studies have revealed famed female fishers from the 1700s, and it is believed that these fisherwomen were more common at that time than once believed. One estimate suggests that as much as a third of one town’s fishing crew were women. It wasn’t until modern concepts of femininity took hold in Iceland in the 1800s that these female harvesters disappeared.

Even in the modern world, women play an essential but often invisible role in fishing. Across the globe, women frequently process and market the seafood once the haul has been brought ashore, but these sorts of roles are often overlooked. The woman workers in the Maine sardine canneries are no different. While men worked at sea harvesting the fish, the women were needed for their small and quick fingers, a job that was considered too cumbersome for the larger-knuckled men.

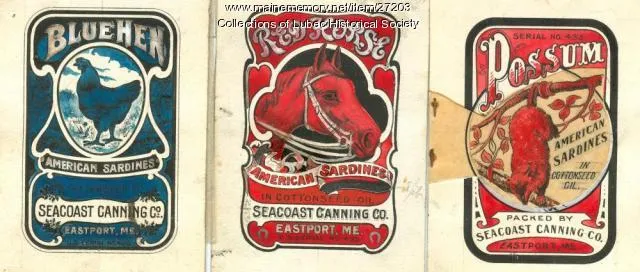

The Maine sardine industry began in 1867, when George Burnham returned from an overseas trip to France and learned of the sardine industry there. It was the first type of endeavor in the States, beginning decades before the first cannery opened in Monterey, California’s famed Cannery Row written about by Steinbeck. In the United States, herring were plentiful, and would supply the industry with small and flavorful fish (a sardine is not a specific species of fish, rather, it is a term to refer to fish of the clupeoid family that are packed and preserved in oil). The foggy Maine weather proved to be too damp to successfully dry out the fish as done in Europe, so while Burnham was unsuccessful in his attempt to run a plant, others soon established new methods that worked for the New England climate.

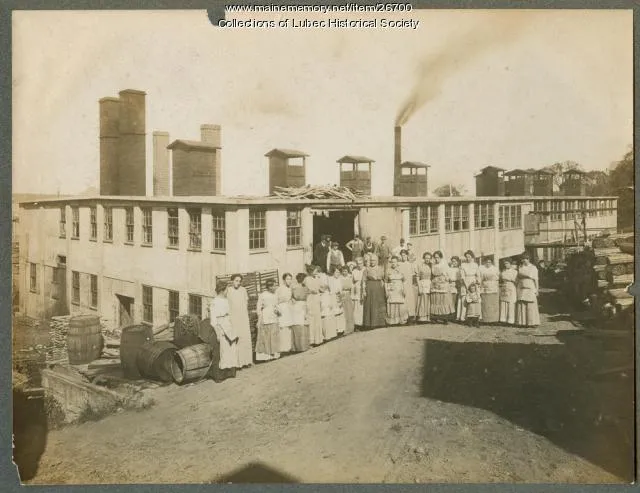

By the early 1900s the industry was at its peak. People living from miles around would commute to the port towns where large cannery warehouses were propped on the water’s edge. Since workers rarely had their own means of transportation, often, a cannery owned pickup truck or bus would make the rounds every morning, picking up the workers on hour-long routes through the countryside.

At the cannery, the fish were cooked, canned, and shipped out. The fish would be pumped out from the sardine carrier boats and into the factory. In some plants the fish would be cooked first (either boiled, steamed, or oil-fried) before they were packed in the cans. Next, the cans were sealed and sterilized before making their way to the casing room where the cans were cased up for shipping.

The female packers were a major part of the canning process. It was their job to cut the cooked fish to size by shearing off the heads and tails, and packing them in the tins. In later years the cutting process was mechanized, but early on a packer relied on her sheers, a set of sharpened scissors that sped up the cutting process. Lela Anderson, the fastest packer in her plant, was known for her special technique of flipping her fish in the air to cut the head and then the tail. In an interview with Keith Ludden for Oral History and Folklife Research in 2011 she explained,

“Well, a lot of them didn’t turn them, they’d just took the scissors and went under-handed. I wouldn’t do that, because I was left-handed, but I’d cut the fish with my right hand. I threw my fish up in the air, and when it come down, I’d cut. That’s why the people when then they come in the factory [and] visited they always wanted to come to my table. Said, ‘We’ve got to see that little girl that flips them fish.’”

Once the fish were cut, they were fit in the tins. A packer’s pay was determined by the number of tins they could fill in a day. Often, base pay was determined by a set number of cans—if you couldn’t fill that number, you were either let go or reassigned to a different part of the canning operation. Every tin filled beyond the base number would add a couple of cents to a worker’s paycheck.

Besides providing a means of stable income, jobs at the cannery created tight-knit bonds among the workers. With their hands busy slicing and packing, it was easy to spend the whole day chatting away. The workers would even get into mischief with one another, playing practical jokes and pranks on the factory floor. When asked, many women commented how the cannery was their second home. “Mostly being with a bunch of good friends. I think that was the best part of it,” said Arlene Hartford, packer at the Stinson plant, to Ludden.

By the early 2000s, the Maine canneries struggled due to several emerging factors. While sardines were once considered a staple in appetizers, the blue-collar lunchbox, and as bar snacks, following World War II the small fish fell out of favor. The invention of steam-powered boats enabled foreign ships to harvest tons of herring from Maine’s shores, reducing the available catch for the US fishery. And, due to a massive marketing effort, tuna became the new favorite canned fish. Additionally, changes to regulatory codes made it difficult for the family-run businesses to remain profitable. In 2010, the last Maine cannery closed its doors.

For the workers who had spent their lives growing up among the canneries and later working at them, the closures were devastating. It was an end of an era in American fishing, leaving a hole where once there was a reliable, respectable job that many were proud to be a part of. Hartford was working at the last plant when it closed. “It was leaving your second home I guess. I guess that’s how you describe it. After all those years, I mean forty-some-odd years. How would you feel?”