No Longer Anonymous: Anna Atkins and her Algae

In the 1850s, a new image capturing technology called photography was just in its infancy. Initial adopters captured primitive images on silver-coated plates, and a whole new world was opened to people wanting to see places from around the globe. In the world of marine biology and botany, the technology also made its mark. Naturalist Anna Atkins printed stunning blue and white negatives of algae using a process that made cyanotypes. Her endeavor to document ocean life using the high-tech process led to what is likely the first published book of photography.

Very little is known about the life of Anna Atkins. Her father, John George Children, was a well-known fellow of The Royal Society and the collections manager of the zoology department at the British Museum. It was through her father, with whom she was very close, that she became exposed to the world of natural history and began her work in both botany and scientific illustration. Her father’s 1823 English translation of a famous seashell book by French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck required drawn illustrations to accompany the text. Atkins meticulously drew the seashell specimens to be scientifically accurate, a tedious task that was great practice for her later work with photographic cyanotypes.

Atkins was also a self-driven naturalist, collecting and preserving plant and algae specimens from the English countryside of Kent for her own personal herbarium. Much of what she learned was likely self-taught, though it is known that she closely followed the works of Sir William Hooker, the director of the Kew Gardens in London. In total she preserved around 1,500 specimens that she later donated to the British Museum in 1865.

The announcement of the discovery of photography in 1839 made headlines across the world when Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre in France and William Henry Fox Talbot in England revealed their work. Atkins’ father personally witnessed the development of photography as a member of the Royal Society and even chaired the meeting where Talbot disclosed the process to its members. Talbot continued to personally correspond with Children about his work in photography, often sharing new insights and photograph samples. Children would then confer with his daughter, with whom he lived at the time, about the new discoveries and together they would produce photographs using a camera and the new process.

While Talbot continued to perfect his early methods of photography, Sir John Herschel began work on his own method of photography, what is now known as the blueprint, and was then known as the cyanotype, named for its bright cyan blue color. While Talbot’s process was complicated and required the use of silver, an expensive metal, Herschel’s method only required mixing two inexpensive chemicals and light exposure. The final product, however, was always in shades of vibrant Prussian blue. For Atkins, it was a perfect means to produce a book depicting her botany specimens.

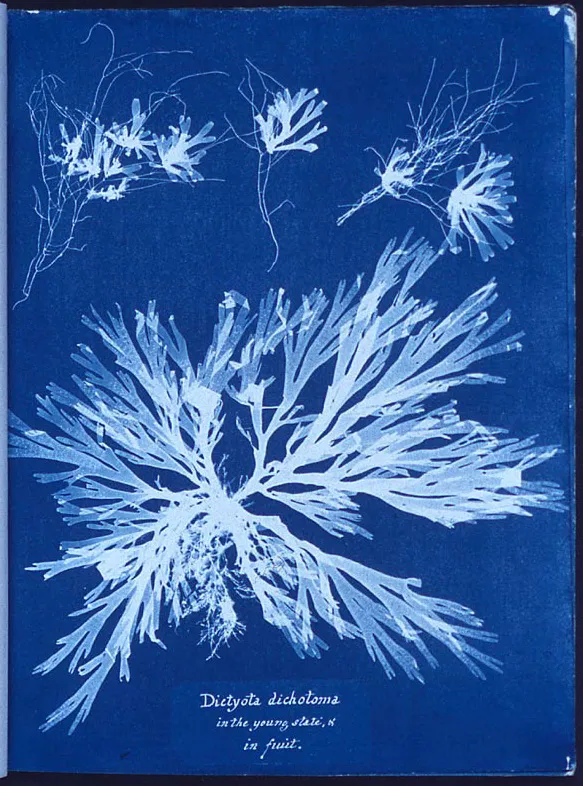

In the introduction of her book Atkins writes, “the difficulty of making accurate drawings of objects as minute as many of the Algae and Conferva has induced me to avail myself of Sir John Herschel’s beautiful process of Cyanotype, to obtain impressions of the plants themselves, which I have much pleasure in offering to my botanical friends.”

Cyanotypes are made by laying a subject material directly on a piece of paper that has been brushed with the iron salts ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide. Atkins likely fixed the algae to the paper and then covered it with a glass panel before letting the whole package sit exposed to the sun for 15 minutes. The final product was a vibrant blue paper with the image negative in shades of light blue and white.

Though less time consuming than the silver-plated photographs of Talbot, Atkins and likely her servants spent hours tediously preparing each cyanotype plate. The roughly 400 plates produced in the final version of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions were produced over several years and in many parts which were then organized in three volumes. The first part was produced in the early 1840s and distributed starting in 1843. At least 10 copies were distributed to friends, institutions, botanists, and notable photographers, including Talbot and Herschel.

It was the recipient’s duty to assemble and bind the book upon possession, and as each part was released the plates were added to the book. Since it was the recipient who bound their own copy, each book is uniquely bound with whatever they chose. Originally softbound, many copies are now hardbound according to the library that owns them. Often plates are missing, or replacements were sent separately and so the total plate count differs slightly from copy to copy. The British Library owns the largest book with 411 plates.

Soon after the original book owners passed away, Atkins and her photography books were forgotten. Often, her books were signed “A.A.” which many people wrongfully assumed was short for Anonymous Author. It wasn’t until the 1970s that her contributions to both photography and botany were properly recognized.

Atkins not only published the first book of photography but would go on to produce photography books of ferns and other plants. Today she is recognized as a pioneer in both photography and the natural sciences and often her photos are displayed as works of art. Her contributions shed light on the role of women in the Victorian era and show that art and science, when melded together, can produce content that transcends time.