Wood Under Sand: The Search for A Slave Shipwreck

A select few wrecks become destinations for the intrepid explorer—perhaps the ship was a casualty in a famous battle, a vessel with possible sunken treasure, or an epic loss of life like the case of the Titanic. The mystery of a shipwreck is a powerful lure, yet one particular shipping trade is noticeably missing from the inventory of discovered and explored shipwrecks. The transatlantic slave trade populated the Atlantic Ocean with over 36 thousand ships as they shuttled human cargo from Africa to the new world from the 16th to 19th centuries, and invariably a few hundred of these ships fell victim to the hazards of the ocean. But up until only a few years ago, not a single slave ship that sank with slaves on board had ever been discovered.

After an exhaustive, multiyear search, in 2013 a team of researchers from several institutions, including the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), uncovered the remnants of the slave ship São José Paquete d’Africa (the São José for short) off the coast of South Africa. The wreck is little more than pieces and bits—shards of wood and a few remnants of iron and copper, hardly the image of the wooden sailing vessel many might envision. Although upon first glance these remnants may seem like trivial debris of little importance, the artifacts left behind hold hidden clues about the intricate and complicated story of slavery.

“So much of human history is unreported in books and manuscripts, on paper,” says Paul Gardullo, curator at NMAAHC and of the Slave Wrecks Project, an international network hosted by the Museum. “A fuller history of humankind can be found in its artifacts—the artifacts of common people the world over are not found in museums. They’ve typically been buried and they have to be unearthed and documented to be understood more completely. When it comes to slavery, these shipwrecks can help us to better understand the story of the slave trade.”

The unearthing of the São José is a story of discovery, one which took years of detective work, both in old archives and in scientific laboratories. It is also a story of recovery. The recovery of a past that has been shut away, forgotten and purposefully unremembered—a past shared by people, countries, and continents apart.

Under the Lion’s Head

On a stormy, late December morning in 1794, 212 slaves lost their lives during the sinking of the São José. The ship was en route from Mozambique on the East Coast of Africa to Maranhao, Brazil—the colony of its sponsored nation, Portugal—and on board were 512 slaves. Docking in Cape Town, South Africa was a necessary pit stop to resupply for the long trans-Atlantic journey. The Cape Town port is a notoriously tricky one because of both the physical obstacles, like powerful currents and hidden outcroppings, and the unpredictable weather. A sudden shift in weather prevented the São José from making safe harbor in the bay, and a storm combined with this hazardous geography led to the ship’s grounding on two reefs. The ship began to take on water and soon was claimed by the sea.

At the onset of the Slave Wrecks Project, the details of the above account were unknown. In fact, very little was known about the ship except for a cursory mention of its demise in a 1794 journal from the Dutch East India Company stating, “a Portuguese ship ran aground in a place called Camps Bay and 200 of the 500 slaves on board perished.” Hardly an “X marks the spot” situation. For two years the Slave Wrecks Project teams scanned the Camps Bay area using a metal detecting magnetometer hoping to find nails or anchors from the São José. Instead, they uncovered rusty pipes and metal shrapnel—modern debris that was a source of momentary false hope. Finding the São José, it seemed, would require more detective work.

In the dusty archives of the Dutch East India Trading Company, Jaco Jacques Boshoff, an archaeologist with the Iziko Museums of South Africa and founding member of the Slave Wrecks Project, uncovered a key clue to the location of the São José. It was here that a deposition given by the São José’s captain unveiled why the endless hours of scouring Camps Bay had been fruitless.

The deposition reads, “…at two o’clock in the morning, as they sought to resecure anchors belatedly noticed as having been dragging throughout the night, the ship struck a rock and started taking water while, according, to the Captain, under a well-known landmark: the Lion’s Head.”

The Lion’s Head is indeed a well-known landmark, even today. The prominent rock outcropping looms above a cove by Clifton, just north of Camps Bay. The Slave Wrecks team was searching in the wrong place.

Revealing the São José

Under six feet of sand in Clifton cove lies the remnants of a wooden ship. The ship bears no markings of identification—only the hard work of an underwater archaeology team can piece together the name of the wreck from clues left behind. Like crime scene investigators, an international team led by Iziko archaeologists meticulously collect bits of wood and metal, carefully vacuuming sand away with a powerful dredging tool and recording the object’s place before removal—all while encumbered by bulky SCUBA gear and being tossed by the strong currents of the sea.

“Identifying any shipwreck is a little like trying to piece together a puzzle in which half the pieces have gone missing, while some of those that remain have been thrown into a blender,” says SWP founder and co-Director Steve Lubkemann of George Washington University in the book From No Return. Each bit has a part to play in identifying the ship. An oversight could potentially hold a missing clue.

We now know from careful analysis of the wreckage that the ship is almost certainly the São José. Microscopic analysis of wood pieces found on site reveals both a rare hardwood, Dalbergia melanoxylon, found in Mozambique, as well as an East African mangrove wood present in the wreckage. The hardwood is thought to be cargo that was to be sold in Western markets and the mangrove wood a repair to the ship, as newly discovered archival records indicate European ships were frequently repaired in Mozambique. Copper sheathing and a unique pulley block, both used in the latter part of the eighteenth century, are consistent with the time when the São José was built.

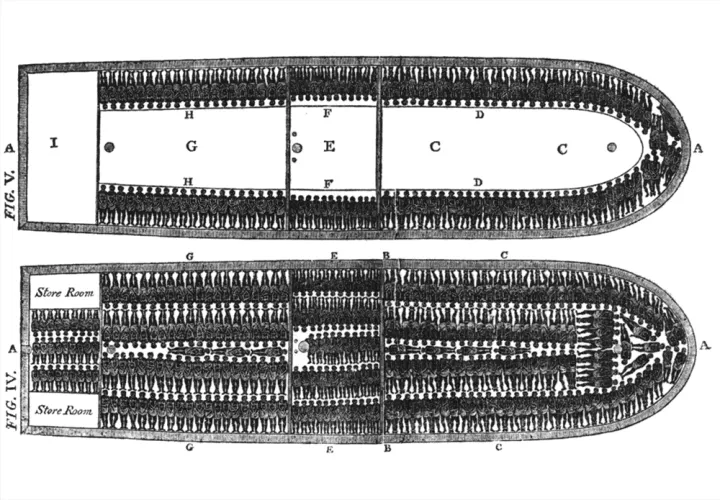

Other evidence reveals that this ship was used for transporting slaves. As iron degrades underwater, marine organisms consume the iron particles and deposit a concrete mass around the object. X-rays of iron concretions at the wreck site show a cavity where the solid iron once existed—in this case in the shape of a horseshoe, the same shape as shackles. The discovery of iron ballast bars also points to the ship’s role in transporting slaves. These bars were used to balance the ship when it carried mostly human cargo but were not needed when the majority of the cargo was much heavier and stackable goods, such as gold or wood. A search in the Lisbon, Portugal shipping records uncovered the original manifest of the São José, and among the cargo was listed 1,130 iron bars.

Taken together – the archival records from the Dutch officials in Cape Town and from Portugal, the location, and the archaeological finds on the site – convincingly support the identification of the wreck as the São José. “Suddenly, although you don’t have the smoking gun, you have everything but,” says Gardullo. “All the various circumstantial evidence were laid out. At that point, the team became pretty darn sure.”

The Future

Finding the São José united people from around the globe. Now as its story is communicated to people from Africa to South America and North America, those who began the Slave Wrecks Project hope others will become motivated to both understand the complexity of slavery and remember the people affected by it. Future projects in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Senegal, Brazil, Cuba and the continental United States are already being planned and discussed.

For Gardullo, the project has made a lasting impression, and he recognizes that the ship’s story has the power to open up discussion on an underrepresented topic of history. “The hunger people have to learn more about it. That is profound, because typically when we thought about these questions of slavery we’ve often been afraid, people will say ‘That’s a hard subject.’ And it is. But when presented in the right way, when presented with complexity and truthfulness and in an engaging way, people are being changed by it across the globe. That is so heartening.”