Kelp and Kelp Forests

Introduction

In the ocean, forests filled with life grow in coastal waters across the globe. Rather than trees, these forests are built by billowing seaweed—kelp. Kelp are algae that grow using the sun’s energy, much like marine seagrasses and plants on land. They are critical habitats that provide a home for other ocean life and protect coastlines. Among the kelp fronds fish, crustaceans like crabs, sea stars, and other sea creatures seek refuge from the tumultuous open ocean. Baby fish hide from predators before they grow to their adult size. Kelp also protect coastlines from erosion, an important role in a world where sea level is on the rise and storms are becoming more frequent. As the ocean warms and humans continue to develop coastlines, it’s important to remember the kelp forests, and protect this valuable ecosystem from destruction.

What Are kelp?

The Macroalgae

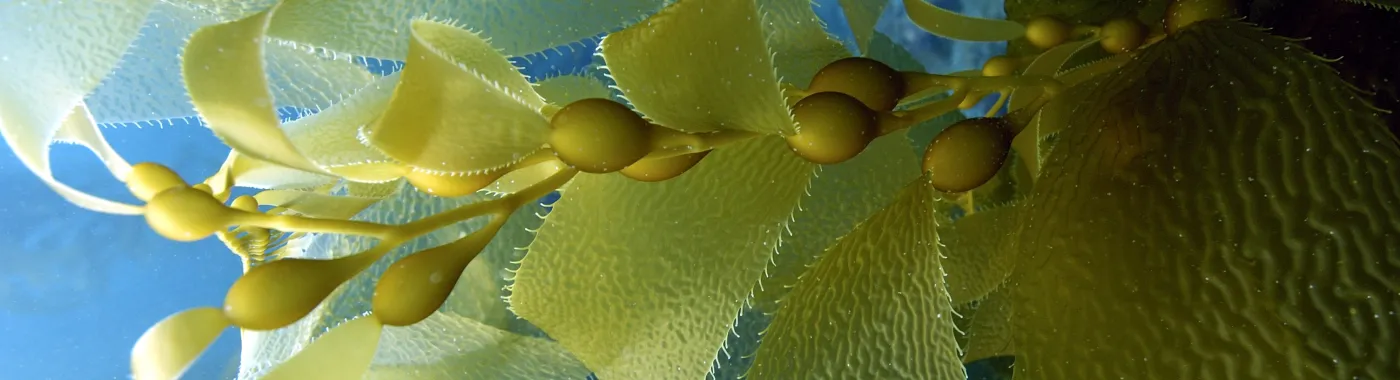

Despite their appearance, kelp are not plants. They are grouped within the algae, also known generally as the seaweeds. Algae are similar to plants in that they use photosynthesis to harness the sun’s energy to convert carbon dioxide and water into oxygen and sugars, which they then use for growth. But while plants rely on roots to secure them to the ground and structured vessels to transport nutrients, algae hold onto the seafloor using holdfasts and transport nutrients from cell to cell. In general, the kelp anatomy includes a root-like holdfast, a stem-like stipe, and leaf-like fronds. Some species also have a bulbous, air-filled bladder called a pneumatocyst that helps the heavy frond blades float to the surface where there is ample sun.

Within the algae there are three major groupings: the green algae, red algae, and brown algae, each named for the general color of their foliage. Kelp are a type of brown algae in the order Laminariales and get their color from an abundance of plant pigments called fucoxanthin. Just as plants get their green color from the pigment chlorophyl, algae get their color from pigments too.

When many kelp grow together in dense clusters over a large area they form a kelp forest. Kelp forests can consist of one kelp species or many. In general, kelp forests can consist of giant kelp (Macrocystis), bull kelp (Nereocystis), horsetail kelp (Laminaria), grey weed (Lessonia), and bamboo kelp (Ecklonia). Multiple species in a forest create a three-dimensional habitat similar to a tropical rainforest on land. Kelp forests can have a sunny canopy, shaded understory, and darkened seafloor. Often, the kelp understory and seafloor also include other algae species.

Where Are Kelp Found?

Kelp are found in temperate and polar regions in coastal waters across the globe. About 25 percent of the world’s coastline is covered in kelp forests. In general, kelp grow on rocky seafloors in water temperatures between 42 and 72 degrees Fahrenheit (5-20 oC) and ocean depths between 50 and 130 feet (15-40 m) with some species growing at deeper depths —one specimen of Laminaria rodriguezzi in the Smithsonian collection was found at 256 feet (78m). However, a few tropical species, like the new species found in the Galapagos, exist in warmer water. Kelp require nutrient rich waters to support their rapid growth, so they often grow near upwelling, or places where nutrient rich water from the deep sea flows to the surface. Also, the clearer the water, the deeper they can grow since sunlight can penetrate farther down into the water. The largest kelp forests are found off the coast of California, Alaska, Nova Scotia, South Africa, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Iceland, Norway, the UK, and Chile.

Growth and Reproduction

On land plants rely on flowers, seeds, and pollen to reproduce. In the ocean the algae rely on spores. These spores drift in ocean currents, much like pollen and seeds float in gusts of wind.

The lifecycle begins when an adult kelp releases spores from special reproductive “sorus” tissue into the open ocean. These spores drift for a couple of days and then settle on the seafloor where the spores grow into either a male or female. This microscopic stage of life is called the “gametophyte,” and it is the life stage that initiates sexual reproduction.

A fascinating part of the kelp life cycle relates to their DNA. All life stores their genetic code using DNA and the DNA is organized within one or multiple chromosomes. Unlike animals such as fish, dogs, and humans that have their DNA organized within two sets of chromosomes, the kelp’s gametophyte life stage only has one set of chromosomes. When the male gametophyte produces sperm and the female gametophyte produces an egg each consists of one chromosome. When a sperm and egg fuse the resulting offspring has two sets of chromosomes.

Both the male and female gametophytes expel their sperm and eggs into the open ocean. By chance, only a select few sperm will ever bump into an egg. When a sperm and egg do fuse, they each contribute one set of chromosomes to the newly formed kelp youngling, also known as the “sporophyte”. This second adult life stage will grow into the large, leafy kelp that we all think of when we think of kelp. After the sporophyte kelp matures the cycle repeats.

Kelp Diversity

There are 182 species of kelp divided into 8 families. Within the 8 families the kelps are further divided into about 30 groups or “genera”. Here we describe the 7 genera commonly found in kelp forests.

Macrocystis- The giant kelp is not only the largest of all the kelps, but the largest algae. A single giant kelp can grow to be over 200 feet (60 m) tall at a rate of 2 feet (60 cm) per day. At the base of their blades are several air-filled pneumatocysts. The giant kelp form the upper canopy in a kelp forest. It is a perennial, meaning once it grows it can live for several years.

Nereocystis- Bull kelp is one of the largest kelp. It is easily identified by the single air bladder at the base of its many blades. Like giant kelp it forms the canopy of kelp forests. Bull kelp are annuals, only living a maximum of 18 months.

Laminaria- There are 31 species of laminaria, also sometimes called horsetail kelp, devil’s apron, sea colander, or tangle. They prefer colder water and are often found in the polar regions. Laminaria are often at the base of a kelp forest, lying closer to the seafloor than other, larger kelps.

Lessonia- Lessonia often form kelp forests in the southern hemisphere. They grow in shallow coastal waters up to 80 feet (25 m) that are often exposed to waves. The Lessonia are highly sought after as a raw material for cosmetics and pharmaceuticals and are one of the most harvested algae in the world.

Ecklonia- The Ecklonia are 10 species of kelp that include the forest forming bamboo kelp. Bamboo kelp dominant shallow coasts off the coast of South Africa and measure up to 33 feet (10 m). Bamboo kelp have one air bladder at the base of their blades.

Alaria-The winged kelp or ribbon kelp are smaller kelps that can form dense beds in the coastal intertidal. They are common off the shore of Maine, Nova Scotia, and Ireland. Alaria can also form the forest understory alongside taller bull kelp and giant kelp. Depending upon the species, mature Alaria can grow between a few feet to over 10 feet tall (3 m). They have one thick blade which is why they are often called ribbon kelp.

Kelp Forests as Ecosystems

Key Services

Modification of the Physical Environment

Kelp forests alter the physical environment wherever they grow. The dense growth dampens the strength of waves and currents, which create protected areas in coastal seas. Not only is the water calm, but the coasts are also protected from the physical blows of waves. When storm waves and tidal surges hit the kelp, their impact is softened. This is especially important for reducing coastal erosion.

Another way kelp alter the environment is through sedimentation. Currents slow near kelp forests, and the floating sediments carried in those currents are able to settle in the calm water. Also, kelp create shade. The shallow waters along the seacoast are normally flooded with sunlight. But the dense foliage of a kelp forest blocks sunlight from streaming to the seafloor, plunging a relatively shallow place into darkness.

Creation of Living Habitat

Like trees in a forest, kelp create a sheltered environment where sea creatures can call home.

Kelp fronds provide a physical surface for growth and resting that would otherwise be open sea. At the surface, the tallest fronds weave a floating canopy. The canopy provides physical habitat where snails, crabs, and urchins that cannot swim can live near the surface in an otherwise deep place.

For swimming species, not only is the understory a great place for ample food, it is also a great hideout to avoid predators. Many crabs, shrimp, and fish will spend the early stages of life within the safety of the kelp roots before making their way out into the open ocean as adults. For this reason, kelp forests are considered nursery habitats. Kelp forests are also a safe place for young otters, whales, and seals to rest.

Foundation of Coastal Food Webs

Food webs require a source of energy. That energy comes from the primary producers, or the plants and algae that convert the energy of the sun into food through photosynthesis.

Kelp are primary producers and a great food source for grazers. The live fronds are eaten by herbivores like urchins and mollusks such as limpets, but the greatest food source comes in the form of detritus. Detritus is dead and decaying tissue. When kelp fronds break or are stripped from the seabed in storms they are eaten and broken down by bacteria. The decomposed particles are then consumed by worms, sea cucumbers, barnacles and other filter feeders. Another source of food comes from the algae that grows in a thin layer covering the kelp fronds. Filled with primary producers, forests are places with ample food- they are some of the most productive places in the world. Kelp and other algae provide a foundation for consumers to thrive. Abundant food means abundant animal populations, and kelp forests teem with crustaceans, mollusks, fish, and mammals. Some species are only found within kelp forests. The blue hottentot fish only lives in the bamboo kelp forest of South Africa and the leafy seadragon and dumpling squid only live in the kelp forests off Australia.

A classic example of kelp food webs are the Alaskan forests. The kelp forests of Alaska remain a well-balanced food web due to the presence of the otters, also known as “keystone” species. Keystone species are species that are critical to maintaining the balance within a food web. While the loss of one species in an ecosystem is hurtful, other species can usually fill the void--

lose a keystone species and the entire system falls into disarray. In Alaska otters are voracious consumers of sea urchins, spiny invertebrates that feed on the kelp foliage. Without the otters to keep the urchin population in check, the kelp forests would be mowed down and a desolate “urchin barren” would emerge in its place.

Off of California, urchin barrens have replaced many of the historic kelp forests and scientists attribute this decline to the loss of the sunflower sea star in this area. Like the sea otter, the sunflower sea star is a voracious predator that controlled the urchin population. In the early 2000s a devastating wasting disease wiped out almost all the sunflower stars and since the outbreak about 90 percent of northern California’s kelp forests are gone.

Blue Carbon

Kelp forests are excellent at absorbing and storing carbon from the atmosphere. As the kelp grow, they take the carbon from atmospheric carbon dioxide and use it as the building blocks for their fronds, holdfasts, and stipes. Once the fronds break from waves they fall to the seafloor and take the stored carbon with them to be buried in the soil. This buried carbon is known as “blue carbon” because it is stored underwater in coastal ecosystems. Often, mangrove forests, seagrass beds and salt marshes are considered the main ecosystems that store blue carbon. Kelp forests store carbon too, and though they cover less than 0.1 percent of the sea, kelp likely account for 3 percent of the ocean’s sequestered blue carbon. One study of kelp forests near Vancouver Island in Alaska found that the presence of sea otters in a kelp forest doubled the amount of blue carbon stored by kelp.

Creatures of Kelp Forests

Sea Urchin

Sea urchins thrive in kelp forests worldwide. They are important herbivores that munch on the kelp fronds. In a healthy kelp forest they graze on broken kelp fronds and ensure that the kelp forest remains a vital and healthy ecosystem. However, in many kelp forests across the globe urchin populations have exploded due to a loss in natural predators and this has devastated kelp growth. Now, urchins are often seen as a nuisance.

Sea Otter

Sea otters are home among the kelp fronds. These furry predators prey upon urchins and keep their populations in check. For many kelp forests sea otters are keystone species. This means that they are a lynch pin to the system, and without their presence the entire ecosystem falls apart. This is especially true in southern California where kelp forests are in significant decline. When they sleep, they wrap themselves in the kelp fronds to keep from floating away.

Cod

Groundfish like cod are voracious predators that eat smaller fish, crabs, and octopus. Bottom dwellers, they live at the base of the kelp forest. Juvenile cod are especially reliant on the protection provided by kelp since they are vulnerable to being eaten by larger predators. Cod are economically important fish and support the livelihood and dietary needs of many coastal communities.

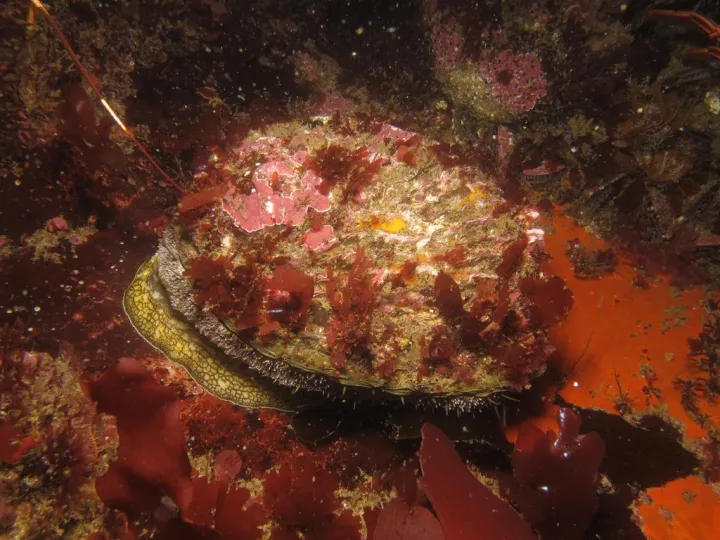

Abalone

The abalone are large snails that feed on kelp. They ensure a thriving ecosystem by clearing enough habitat for new, vital kelp to grow. Abalone shells have a beautiful inner nacre or mother of pearl. Recent overharvesting of abalone has become an issue worldwide, and many species are now listed as threatened by extinction.

Wrasse

Wrasse, a diverse family of fish found in kelp forests worldwide, stalk prey in the dark cover of the kelp understory. As voracious predators, wrasse help regulate populations of sea urchins, which are notorious for overgrazing kelp if left unchecked. By keeping herbivore populations in check, wrasse indirectly protect kelp forests from harm and promote their growth and resilience. Additionally, wrasse are important prey for larger predators, contributing to the intricate food web dynamics of kelp ecosystems.

Pyjama Sharks

The pyjama shark (aka pajama shark or striped catshark) is one of many shark species that call kelp forests home. These specific sharks live in the kelp forest of South Africa. Despite their small size, they play a crucial role in the ecosystem as both predators and prey. Pyjama sharks feed on a variety of benthic invertebrates, helping to control populations of species like sea urchins that can graze on kelp. Additionally, they serve as prey for larger predators, contributing to the intricate food web dynamics of kelp forests. Their presence helps maintain the balance and health of South Africa's biodiverse kelp ecosystems.

Grey Whales

In California, grey whales are frequent visitors to kelp forests. The whales seek out the kelp for shelter, often to avoid predators like the killer whale. They also feed on the buffet of small invertebrates and crustaceans that are abundant among the kelp fronds.

Sunflower Sea Stars

The sunflower sea star is a many-armed star with a voracious appetite for sea urchins. A sunflower sea star can travel at speeds up to 40 inches per minute, fast enough to snag and engulf scuttling crabs. Sea stars rely on the strength of their arms and tube feet to pry apart the urchins’ shells and they then expel their stomach to devour the tissue within.

Stellar’s Sea Cow (extinct)

The Stellar’s sea cow, a now extinct manatee-like mammal, was once a key animal that lived in Alaska’s kelp forests. Their presence in the forest likely affected kelp forest growth, as they fed on kelp vegetation and likely disturbed the seafloor sediment. Today kelp forests grow in dense thickets, but it is likely that sea cow grazing on kelp allowed for other algae to thrive. These other algae were potentially an ample food source for urchins, which would ignore kelp in favor of this other food source. Researchers also suggest that sea cow presence helped make kelp more resilient to temperature swings. Due to overhunting, the Stellar’s sea cow went extinct by the end of the 18th century.

Human Connections

Humans rely on kelp forests across the globe. Though it is difficult to know exactly how much kelp forests contribute to the world’s economy, it is estimated that they are worth over $500 billion dollars. Kelp forests provide resources and services in many aspects of our life. The most evident way they provide for humans is through the fishing industry. Kelp support commercial fisheries by providing habitat for economically important fish species like cod and rockfish, sustaining coastal economies reliant on fishing industries. But kelp’s services go beyond fishing. Additionally, kelp forests contribute to ecotourism, attracting divers, snorkelers, and wildlife enthusiasts eager to explore their rich biodiversity. Kelp also serves as a valuable source of food and raw materials, with seaweed cultivation and harvesting industries producing food products, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and agricultural fertilizers. Furthermore, kelp's role in carbon sequestration and shoreline protection offers indirect economic benefits by mitigating climate change impacts and reducing coastal erosion costs.

Kelp Cuisine

Kelp serve as a vital food source globally, with diverse culinary applications. In Asian cuisine, particularly in countries like Japan, China, and Korea, kelp play a prominent role. Known as "kombu" in Japanese cuisine, it's used to make dashi, a flavorful broth that forms the base of many Japanese dishes. Kombu is also added to soups, stews, and simmered dishes for its umami-rich flavor and nutritional benefits. Additionally, in Korean cuisine, kelp, known as "dashima" or "dasima," is used to make broth and as a wrapping for rice and other ingredients in dishes like kimbap.

Indigenous communities along the Pacific coast of North America, such as the First Nations in Canada and Native American tribes in the United States, have a deep-rooted culinary tradition that includes the use of kelp. One common way indigenous communities used kelp was by drying it to preserve it for long periods. Dried kelp could be stored and used as a food source during the winter months or when other food supplies were scarce. It was often rehydrated and incorporated into soups, stews, and broths, providing essential nutrients such as vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Additionally, kelp was sometimes roasted over open fires to enhance its flavor and texture. This created a crunchy snack similar to seaweed chips. It was also used as a wrapping for cooking and preserving other foods, such as fish and shellfish, imparting a subtle oceanic flavor to the dishes.

Indigenous Australians have also historically incorporated kelp into their diets. Similar to Indigenous communities along the Pacific coast of North America, they often dried and roasted kelp to preserve it for consumption. Dried kelp could be rehydrated and used in soups, stews, or eaten as a snack. In contemporary Australian cuisine, chefs and home cooks have begun to explore the culinary potential of kelp. Dried kelp flakes or powder are sometimes used as a seasoning or flavor enhancer in dishes such as soups, salads, and seafood dishes. Kelp can also be added to bread or pasta dough to infuse a subtle oceanic flavor. Seaweed salads are also becoming popular. These salads often combine sliced or shredded kelp with other types of seaweed, vegetables, and dressings, creating a refreshing and nutritious dish.

With the increasing interest in sustainable and plant-based ingredients, experimentation with kelp as an alternative food has become increasingly popular. Plant-based burgers, sausages, and snacks often rely on kelp's nutritional profile and umami-rich flavor to make them both appealing and satiating.

Farming

Kelp is used as a fertilizer for farming because it's packed with nutrients that help plants grow big and healthy. Farmers use kelp in different ways to give their crops a boost. They can either mix dried and ground-up kelp directly into the soil or make a liquid fertilizer by soaking kelp in water. When plants absorb the nutrients from the kelp, they grow stronger roots, greener leaves, and produce more fruits or vegetables. Kelp also contains helpful substances that protect plants from diseases and stress caused by things like extreme weather. Using kelp as fertilizer is like giving plants a nutritious meal, helping them thrive and produce better harvests. It's a natural and eco-friendly way for farmers to improve the health of their crops and the soil they grow in.

Soap and Beauty

Threats and Conservation

Threats

Overfishing

Overfishing is one of the main threats to kelp forests worldwide and has caused significant ecological shifts and biodiversity loss. Though kelp forests are biodiversity hotspots, unsustainable fishing practices have severely depleted these vital ecosystems, triggering cascading effects throughout marine food webs.

One of the primary ways overfishing affects kelp forests is through the removal of key predators, such as sea otters and large fish species like lingcod and rockfish. Research by scientists has shown that when these predators are overexploited, their prey populations, particularly sea urchins, can explode in number, leading to extensive grazing on kelp. This unchecked herbivory can result in "urchin barrens," where kelp forests are reduced to barren seafloor landscapes devoid of complex habitat structures. Also, the removal of large predatory fish can disrupt the delicate balance of kelp forest ecosystems. One study demonstrated that the loss of predators can lead to increased abundances of smaller herbivorous fish species, which in turn intensify grazing pressure on kelp, hindering its growth and reproduction. This imbalance can ultimately lead to the collapse of entire kelp forest ecosystems.

Overfishing also indirectly impacts kelp forests by altering the structure and composition of marine communities. The depletion of fish stocks can lead to a decline in the abundance of herbivorous fish that feed on algae. Without these grazers, algae can outcompete kelp for space and light, further reducing kelp abundance and diversity. Overfishing can also disrupt how nutrients are cycled within kelp forests. A 2008 study found that the removal of large predatory fish leads to less nutrients in the seafloor soil. When fish defecate their excrement settles on the seafloor and provides the nutrients required for healthy kelp growth. Without fish, the fish poop also disappears. This disruption in nutrient cycling can further impair the ability of kelp forests to recover from disturbances.

Urchin Barrens

One of the main threats to kelp forests is the overpopulation of urchins. Urchins are voracious consumers of kelp, but in a balanced kelp ecosystem the urchin populations are controlled by predators such as otters or starfish. When predators are removed, urchins no longer act as scavengers and instead mow down healthy kelp, often decimating entire forests. Warming water and pollution are other factors. Kelp are less resilient to disease and can have trouble establishing themselves in less than favorable conditions. It’s a perfect storm for urchins to take over. With the kelp gone, the once vibrant habitat becomes an “urchin barren” with only urchins covering the seafloor for potentially hundreds of miles. Once an urchin barren establishes it is near impossible to revert to the former ecosystem.

Abalone Poaching

Since the 1990s illegal harvesting of abalone in South Africa has steadily been on the rise. Following the end of apartheid, the South African government redistributed the harvesting quota from white owned companies to black owned companies and in the process left out the traditional and artisanal fishermen who had been relying on the fishery for generations. Without a legal income to rely on, many seasoned fishermen turned to poaching. General poverty in the country is another factor. Thousands of poor and unemployed workers have been recruited as menial laborers within the industry.

Abalone is a sought-after food in East Asian cuisine, with the highest demand in Hong Kong. Though illegal poaching occurs worldwide, about one third of the abalone entering Hong Kong originates from the illicit trade in South Africa. Poachers harvest the snails by scuba diving in the South African kelp forests and then the snails are smuggled into neighboring countries via illicit trade networks to be shipped to China.

The intense harvesting has taken its toll. About 44 percent of worldwide abalone species are threatened with extinction. Perlemoen, the most sought-after species in South Africa, is endangered.

Climate Change

Climate change poses significant threats to kelp forests worldwide, impacting their distribution, abundance, and ecological functions. One of the primary effects of climate change on kelp forests is ocean warming, which can alter the optimal temperature range for kelp growth and reproduction. Warmer waters can lead to thermal stress, causing kelp to become more susceptible to diseases. Additionally, changes in ocean temperature can disrupt the reproductive cycles of kelp, affecting their ability to produce viable spores and recruit new individuals.

Also, like corals, kelp can bleach when stressed. This means that they lose the brown and green pigments that give them their color. Without their pigments kelp cannot photosynthesize and grow. Preliminary studies suggest kelp bleaching may have to do with ocean acidification, the increased acidic nature of ocean water due to warming. The acidity harms symbiotic microbes that live on the kelp fronds and the loss of those microbes then allows disease to bleach the kelp.

Changes in weather patterns associated with climate change, such as increased frequency and intensity of storms and extreme weather events, can also pose challenges to kelp forests. Storm surges, high winds, and heavy rainfall can cause physical damage to kelp forests, including uprooting individuals, breaking fronds, and disrupting habitat structure. These disturbances can impede kelp recovery and regeneration, particularly in areas already stressed by other environmental factors and human development. Overall, climate change represents a multifaceted threat to kelp forests, highlighting the urgent need for effective conservation and management strategies to mitigate its impacts and safeguard these vital marine ecosystems.

Invasive Species

As oceans warm and people develop coastlines, the threat of invasive species continues to be of major concern to the health of kelp forests worldwide. When new species invade a kelp forest, they can cause significant changes to the kelp food web. Algae are especially invasive because they compete for the same light and space that are essential to kelp growth. Species like wakame (Undaria pinnatifida), Japanese fireweed (Sargassum muticum), and dead man's fingers (Codium fragile) are particularly problematic. Similarly, invasive herbivores such as the black sea urchin (Centrostephanus rodgersii) in Tasmania can proliferate in the absence of natural predators, resulting in overgrazing of kelp beds. When urchin populations overgrow, they can form barren areas known as "urchin barrens." Tropical fish that eat algae are also becoming an issue. In Australia, the rabbitfish and drummer fish, two tropical fish, are now found in temperate kelp forests and they are greedily eating the kelp, often reducing forests to barrens. These changes can cascade through the ecosystem, impacting biodiversity, habitat structure, and the provision of ecosystem services, ultimately compromising the resilience and function of kelp forests.

Conservation

Marine Protected Areas

Establishing marine protected areas where fishing and other human developments are restricted or prohibited has been effective in conserving kelp forests. By reducing human impacts within these designated areas, MPAs provide a safe haven for kelp and associated marine species to thrive. Research has shown that well-managed MPAs can lead to increases in kelp abundance, biodiversity, and ecosystem resilience.

One example of a marine protected area that has helped protect kelp forests is the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of California, United States. Established in 1980, this protected area encompasses approximately 1,470 square miles (3,800 square kilometers) of ocean waters surrounding the five northern Channel Islands. One 2013 study, found that kelp forests within the sanctuary significantly recovered after the protection was put in place. Researchers observed increases in kelp canopy cover, density, and size, indicating successful recruitment and growth of kelp populations. The study attributed this recovery to reduced fishing pressure and enhanced protection of kelp habitats within the sanctuary.

Sustainable Fishing

Ocean habitats are often monitored by governments to make sure that fishing and human development do not permanently damage the local fish populations. Historically, this was done by managing one fishery independently of all other fisheries. Implementing ecosystem-based management (EBM) approaches that consider the interconnectedness of marine ecosystems has been beneficial for kelp forest conservation. EBM takes into account the ecological relationships between kelp and other species, as well as the broader environmental factors influencing kelp health. By integrating scientific knowledge and the knowledge of people working along coastlines, EBM aims to sustainably manage kelp ecosystems while balancing human needs and conservation goals.

Restoration Projects

As kelp forests decline, it is important for humans to seek out effective methods for forest restoration. There is no record of natural restoration—any hope to regain lost forests will likely come from human intervention.

Currently, most restoration efforts rely on protecting or reintroducing predators. The earliest and most successful efforts limited fishing or restricted hunting. Often, this was accomplished through the creation of protected areas that banned the harvesting of fish. This method has proven the most useful when restoring large areas. At smaller scales projects that remove urchins can restore small areas of kelp. This is done by either creating a new urchin fishery that targets the problematic species, quick liming, or diving to kill the urchins.

Another method of restoration is through the active growth of new forests. One way to do this is through the dispersal of spores in an area that is otherwise void of younglings. Another is by taking recently fused sperm and eggs and dispersing the resulting young sporophyte into the water. In the Mediterranean, a restoration project successfully restored an algae forest by seeding the area with young sporophytes. Seven years after the project, the forest was still standing and thriving. Active restoration efforts also include transplanting adult kelp from a nursery to the ocean seafloor, and this type of restoration has had mixed results of both successes and failures. Transplanting is difficult due to the nature of working underwater—scuba gear is cumbersome and requires skilled workers and planting sites are often exposed to storms and currents that can easily destroy newly planted kelp. The most successful transplanting project occurred in Australia’s Sydney Harbor where important brown algae called crayweed (Phyllospora comosa) had gone extinct.

Recently, conservation organizations and research institutions in Tasmania have initiated kelp restoration projects aimed at rehabilitating degraded kelp forests. One notable project is the "Reef Life Restoration Program" led by the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) and the University of Tasmania. This project focuses on restoring kelp forests by transplanting juvenile kelp plants onto degraded reefs. Kelp plants are grown in nurseries and then carefully transplanted to selected restoration sites using techniques such as rope deployment or direct seeding. By reintroducing kelp to areas where it has declined or disappeared, the project aims to rebuild habitat structure, enhance biodiversity, and improve ecosystem resilience. Preliminary results from kelp restoration efforts in Tasmania have shown promising outcomes, with transplanted kelp successfully establishing and contributing to the recovery of degraded kelp forests.

Community Engagement

Community engagement in kelp forest conservation takes various forms, involving local residents, environmental organizations, and governments. In California, citizen science initiatives like Reef Check empower volunteers to monitor kelp health and report any concerning changes. In South Africa, organizations like the Sea Change Project involve coastal communities in kelp forest restoration efforts through education and hands-on participation in replanting projects. In Tasmania, the Reef Life Restoration Program engages local people in kelp restoration by providing opportunities for community members to contribute to research and restoration activities. Additionally, indigenous communities worldwide, such as the First Nations in Canada and Native American tribes in the United States, play a crucial role in kelp conservation through traditional ecological knowledge and sustainable harvesting practices, fostering a deeper connection between communities and their marine environments. These examples demonstrate the importance of community involvement in safeguarding kelp forests for future generations.