The Story of Stashed Whale Baleen

In 2012, John Ososky, a specimen preparator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, was presented with a mystery to solve. Stored in the Museum’s offsite Museum Support Center was an orphaned collection of 3,250 whale baleen plates. The large bristly plates grow from the roof of a whale’s mouth and are used to sieve out the tiny krill that they feed on. Several feet long, the baleen in this collection now sat crammed in 30 cases and nobody knew where they came from.

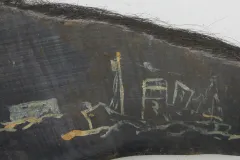

Ososky’s only clue was that each plate had an accompanying wooden tag tied with a small piece of rope. Etched on one side was a Japanese character and on the other a number. With this information in hand, a trip to the Smithsonian Institution’s archives would reveal a compelling story. Correspondence from 1948 between the office of Remington Kellogg, then curator of mammals at the Smithsonian’s U.S. National Museum (today our National Museum of Natural History), and the office of U.S. Army General Douglas MacArthur indicated that this collection had its roots in a post-World War II endeavor led by the United States to keep Japan from starving.

“That was the smoking gun for what it was and where it came from,” said John Ososky.

In the years following World War II, Japan’s infrastructure was devastated and its ability to feed its population was crippled. Recognizing both that the nation was on the verge of starvation and the simultaneous need to rebuild Japan as an ally, General MacArthur rallied support to revitalize Japan’s commercial whaling industry. The idea was far from popular. Many allied nations still considered Japan a military threat and any rebuilding of their shipping fleet was considered a hostile act. Moreover, at the time, whaling nations were in an international debate about the plight of whale populations and many saw Japanese whaling as a threat to their own desire to continue commercial whaling.

Japan’s dire circumstances and need for food trumped these objections, and in 1946 MacArthur authorized whaling expeditions to set out from Japan for Antarctica. To appease the unease felt by the allied nations, two allied representatives would be placed on the ship to ensure the Japanese adhered to correct protocols. MacArthur also reached out to the Smithsonian Institution, and this is where our baleen collection comes into play.

At the time, Kellogg was not only a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum, he was also a highly respected advocate for whale conservation. He had been instrumental in the passing of the first international protection for whales, the International Agreement for the Regulation of Whaling, and was the lead U.S. delegate in subsequent meetings of the International Conference on Whaling. The scientific community in the United States was pushing for an end to whaling, and since MacArthur’s plan directly contradicted this endeavor he wanted Kellogg’s opinion on measures that could be put in place that would be mindful of conservation, or at least minimize the impact of the whaling expeditions.

In his response, found in the Smithsonian Archives, Kellogg recommended three actions. He suggested the inclusion of more freezers aboard the whaling vessels to minimize meat spoilage, he requested that whales too small to be killed would be tagged and described so that they could be studied when spotted in future years, and he requested that the two largest baleen plates from each killed whale be saved and shipped to the Smithsonian. MacArthur deemed the first two requests too burdensome, but the last request he agreed upon.

These are the mysterious baleen plates Ososky found forgotten among the collections. But why was such a priceless collection buried and forgotten? This, too, would be answered by combing through the archives.

With the baleen en route, Kellogg reached out to Japanese scientist Masaharu Nishiwaki about his wish to determine the age of the whales. Kellogg’s idea was that as the whale grows the baleen also grows, much like fingernails in humans. But also, like fingernails, over time the oldest sections wear away. Much to Kellogg’s dismay, Nishiwaki replied that only the last five to seven years of a whale’s life is recorded in the baleen. Frustrated, Kellogg stored the baleen away upon its arrival, never even unpacking it from the boxes.

Though the boxes were moved from one storage facility to the next, they sat unopened for over 65 years.

In that time, memory of the baleen’s origin was lost, along with the data that accompanied the collection. Luckily a call to colleague Robert Brownell at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration helped locate the data. Brownell’s contacts in Japan helped him locate the ship manifests. But even with this document in hand the struggle continued.

First off, baleen is big and bulky. The plates are several feet long and a collection of over 1,600 made it nearly impossible to sort. Also, the baleen came from two expeditions, each using a sequential labeling system starting at one, but none of the baleen plates indicated to which expedition they belonged.

“Going through this baleen and trying to match it up with the manifest was such a mess. It was almost impossible,” said Ososky.

With the help of research assistant Paula Bohaska and several volunteers, Ososky eventually photographed every single baleen plate in an attempt to visually sort the baleen. On a computer screen baleen with serial numbers painted in the same ink, or etched in the same style, could be grouped together.

“I was just hoping that this would work. Miraculously, it did,” said Ososky.

Now, over 70 years after the baleens’ arrival at the Museum, scientists at the Smithsonian are finally able to use the baleen for scientific study. In the time that has passed scientific technologies have advanced to the point where scientists can learn a great deal about the whale’s life history from the baleen. Hormone levels can be measured to indicate stress or a pregnancy. Genetic technology now enables population studies that will show how related and diverse the whales were at that time. Studying the molecular composition of the baleen will enable scientists to determine what kinds of food the whales ate and which oceans they swam in. Taken together, this information can paint an accurate picture of what life in the ocean was like for these whales some 75 years ago and enables us to understand how the ocean and its whales have changed over time.

“As Kellogg might never have guessed, this has become one of our most valuable marine mammal collections,” said Ososky.

Forgetting about the baleen may have been a mistake, but its serendipitous storage allows scientists to fully take advantage of the knowledge the plates hold.