Ancient Architects of the Ocean: How Stony Corals Have Survived Through Earth’s Changes

Just beneath the ocean’s surface off the tropical coast lives one of the oldest living animals on the planet – the beautiful, reef-building stony corals. From family lineages nearly half a billion years old, these corals are the backbones of thriving reef communities. We now know that the key to their resilience and continued survival through time lies in their diverse family tree. Deep-sea relatives that look like snowflakes and live in the dark maintain the ability to thrive in light, and it is their ability to evolve time and time again that makes them survivors.

Recent research led by scientists Dr. Claudia Vaga and Dr. Andrea Quattrini from the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, as well as Dr. Marcelo Kitahara from the University of Sao Paulo, sheds new light on how stony corals evolved and endured through major environmental upheavals. Their survival through mass extinctions, ocean acidification, climate change, and ocean anoxic events provides insight into what the future holds for today’s corals experiencing similar threats. By analyzing DNA from hundreds of coral species collected from around the globe, including specimens housed in museums, they were able to clarify which coral lineages survived past climate crises and what traits helped them persist.

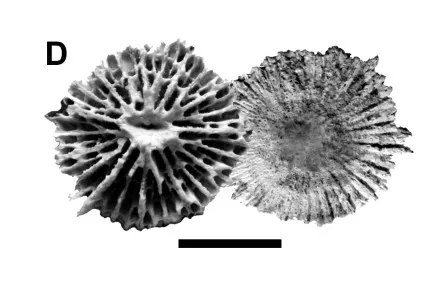

Today’s stony corals are split into two main groups. The first group includes the familiar shallow water corals, recognizable by their bright colors. These corals tend to live in colonies and form symbiotic relationships with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. The algae live inside coral tissues and give their hosts nutrients through photosynthesis, the act of using sunlight to make food. This symbiosis is what allows reef-building corals to thrive even in waters that are nutrient-poor. The other, lesser-known second group includes mostly solitary corals living largely in the deep sea where sunlight cannot reach. These corals lack algal symbionts and instead rely entirely on eating microscopic organisms and organic material that drifts from the surface waters, known as marine snow, for food. Despite their smaller size and solitary nature, these deep-sea corals create complex three-dimensional habitats, just like their shallow counterparts, and provide homes for diverse marine life on the ocean floor.

The Smithsonian and University of Sao Paulo-led study gathered 274 coral samples from museum collections, from the seafloor using scuba divers, and from trawling to better understand coral evolution. Using molecular techniques, they decoded DNA sequences from the coral samples and built a tree, which revealed how different coral groups are related, when certain traits came about, and which traits stuck around after past environmental crises. It was a particularly notable accomplishment because many of the samples were from museum collections and required new techniques to extract the DNA for study.

The scientists found that over the past 200 million years, deep-sea solitary corals tended to survive major global events better than many shallow-water corals species. These deep-sea corals live in parts of the ocean where conditions tend to be more stable and less affected by sudden changes like temperature spikes or low oxygen levels. However, two traits were particularly notable when reviewing the tree—coloniality, or living in colonies, and partnering with symbiotic algae that could photosynthesize. The study found that corals evolved to grow in colonies and have symbiotic algae multiple times, and these traits were rarely lost. This allowed them to adapt over millions of years in the deep and recolonize the shallower waters when the conditions were more fitting. This new understanding is crucial because today most research focuses on shallow corals and the coral bleaching caused by warming and acidification, an important part of coral conservation. However, deep-sea corals also deserve attention as they are not immune to low oxygen zones either. These low oxygen events that occurred millions of years ago are still a possibility today. Changes in ocean temperature can alter circulation patterns, leading to reduced oxygen levels in some regions, posing a threat to coral habitats in shallow waters, making these deep-sea corals vital as they could provide a haven during events such as these.

Looking forward, the findings broaden the perspective in coral conservation efforts to include deep-sea corals. These deep-sea species survived past disruptions and may act as “refuges” that can help recolonize reefs if and when conditions improve. Coral conservation is critical since corals, both shallow and deep, are fundamental to ocean life. They build three-dimensional environments on rocks and sediments that support countless organisms including fish, marine invertebrates, and many commercially important species. Dr. Vaga and Dr. Quattrini emphasize that although the deep sea might seem remote and disconnected from humans, it strongly links with surface ecosystems. Regardless of depth, reefs are the building blocks for flourishing underwater habitats and ecosystems.

The study also shows the potential of museum collections. Dr. Vaga says, “I think there’s a lot of specimens in our museums already and with the right techniques that we’ve really worked on in the last few years, we should really focus on historical museum specimens to create bigger trees and create more projects…” This would open the door to scientists expanding their knowledge without always needing to utilize time-consuming field work, potentially allowing for more accessible and in-depth studies of coral diversity and history.

The story of stony corals is one of adaptability and resilience. Their ability to switch between solitary and colonial forms and to form symbiotic relationships with algae again throughout time shows that life can bounce back even after severe environmental pressures. As we face intense global changes today, these ancient ocean architects remind us of both nature’s persistence, but also of its limits. Although this research provides hope for the future of corals, the work does not stop here. Studying and protecting the full diversity of coral lineages, from the sun kissed reefs to the dark and mysterious depths, is essential to preserving the health of our oceans for generations to come.