7 Ocean Parasites Worth Celebrating on World Parasite Day

For some creatures, having a partner in life is more than a choice, it’s a matter of life and death. Sometimes it’s a case of mutual agreement—two organisms live out their lives benefitting from a relationship, like the clown fish and its anemone host. Other times one partner receives the short end of the stick. That’s the case for parasitic relationships, where one partner harms, or hinders, a host animal that they live on or in.

The ocean is teeming with parasitic partners that leech off of unsuspecting hosts. From jellyfish and corals to fish and whales, all groups of animals in the ocean have parasites. They are an essential part of the ecosystem, providing some level of population control to keep the ecosystem in balance. Because of their need to feed or benefit from another organism without permission, some parasites have truly ingenious methods for staying alive. Here Smithsonian scientist and marine parasite expert Dr. Jimmy Bernot shares seven of his favorite ocean parasites:

The Tongue Eating Isopod

Canker sores are nothing compared to the oral woes of fish infected by cymothoid isopods, also known as tongue-biters. These crustaceans sever the host fish’s tongue, latch themselves onto the remaining nub with hooked appendages, and then nestle down to live in the space vacated by the missing tongue. The isopods then allow the fish to carry on its normal activity, all the while it feeds on the host’s blood. This is the only known instance in the whole animal kingdom where a parasite replaces a host’s organ.

Barnacle Mind Control

Mind control may seem like a power only suited for stories of science fiction, but one barnacle has the manipulation skills to rival a puppeteer. Sacculina is a species of barnacle that infects crabs and then manipulates their behavior to benefit itself—all to the detriment of the unsuspecting crab.

They do so by growing a rootlike system throughout the crab’s entire body, which the parasite uses to feed on the crab. As the parasite develops, part of its body grows outside of the crab on its lower abdomen, right where a crab would carry its eggs. The parasitic barnacle then manipulates the crab by tricking it into treating the parasite like it would treat its own eggs – carefully caring for and nurturing the parasite by protecting it, grooming it, and flushing it with oxygenated water. This happens even in infected male crabs, which start to behave like pregnant female crabs. Meanwhile, the parasitic barnacle castrates its host, depriving it of the ability to reproduce and diverting its energy to care for the parasite.

Giant Parasites

While most of the parasites in this list are ectoparasites (living on the outside of their host) there are also many endoparasites (those that live inside their hosts). These include parasites like tapeworms that usually live inside the intestines of vertebrates. But some endoparasites live in more unusual places. Take for example, the largest roundworm in the world, which is aptly named Placentanema gigantisma. It lives in the uterus and on the placenta of sperm whales, where it can grow to be 24 feet long. As for the longest parasite in the world, that is likely another parasite of sperm whales—the tapeworm Tetragonoporus calyptocephalus—can grow an alarming 90 feet long.

Top of the Food Chain

Life as a great white shark comes with the perk of reigning as top fish in the sea, a predator above all others, or so it would seem. Many sharks actually have unwanted passengers, called copepods, clinging to their skin and gills. They behave like fleas on a shark, although they are only distantly related to the insects known to pester cats and dogs. Still, they feed off of their host in a similar manner. This means the shark parasites, not the sharks, are actually at the top of the food chain. There is even a copepod called Ommatokoita elongata that permanently attaches itself to the cornea in the eyes of Greenland sharks and sleeper sharks.

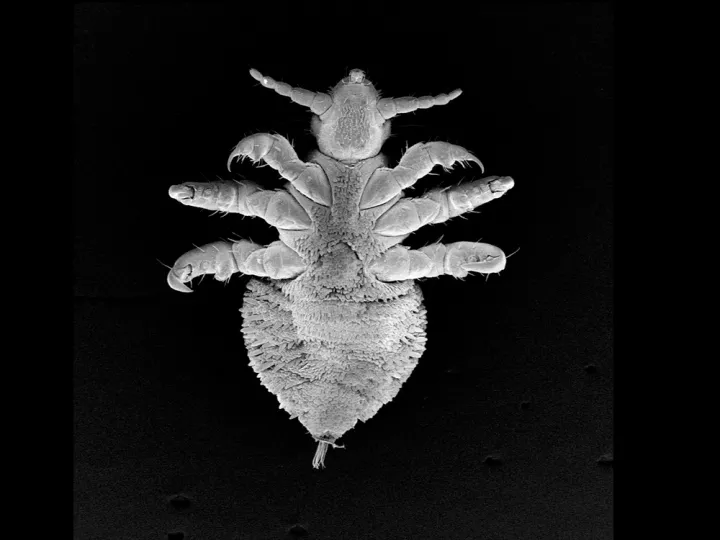

Sea Lice

For the most part, insects live life on land. However, the Echinophthiriidae, a family of lice that infect seals, sea lions, walruses, and otters, have invaded the sea like no other group of insects. While whales and manatees have lost much of their hair, these other marine mammals retained their furry bodies as they evolved from life on land to life at sea, meaning they have the perfect environment to harbor lice – except for their salty habitat. Like their hosts, these lice have evolved amazing capabilities that allow them to survive the hardships of life deep under sea, a place no other insects go. The lice go where their hosts go, which means they often make some of the deepest dives in the animal kingdom. The southern elephant seal makes dives to depths past 2,000 meters, a trip that can last over two hours, and the lice go along for the ride.

Coral Castles for Crabs

Finding a protective home on the seafloor can be important for avoiding hungry, lurking predators. Crevices in rocks may work for some, but gall crabs have figured out an ingenious way to build their own cozy nook—inside growing coral. There are fifty different species of gall crabs, all small in size. To avoid predators, they form depressions in living coral, a small pit or cave that the crab then lives in. The home also provides easy access to food. The crabs feed on mucus that the coral produces and also other algae bits that they can reach from inside their small coral caves. Think about that next time you’re building your own sand castle.

Skin Gaugers

The gaping, toothed mouths of sea lampreys function just as their appearance suggest. The disc shaped suction cup mouth is an excellent tool for tightly latching onto the skin of its host where the lamprey then scrapes through the flesh with a rasping tongue-like piston. Some species of lampreys have tongues and mouths specialized to gauge out pieces of flesh from fish, while other species have mouths specialized for blood feeding. The species of parasitic lamprey that eventually live in the ocean begin their life as larvae in rivers, only turning into flesh-eaters once they’ve reached adulthood.