In the Arctic, the Times, They Are a-Changin: You Can Pitch in to Understand How

Invasive species are often in the news these days, with human-transported organisms popping up in unexpected places. But in this era of climate change, there is a whole new kind of invasive species, those that are taking advantage of changing conditions to expand into areas not previously occupied. Some species may even be returning to a part of the world that they used to occupy, and haven’t seen in hundreds or thousands of years. As a result, we are watching ecological transformations unfurl before our eyes.

We know that the climate of the Earth is changing—the average temperature and amount of carbon in the atmosphere have reached record highs due to our emissions of heat-trapping gasses. Changes are particularly rapid in the Arctic, where warming is happening faster than anywhere else on the planet. Melting Arctic sea ice is opening up channels between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and the resulting interchange of marine mammals and birds is one that hasn’t occurred in millions of years. A new paper from Smithsonian researchers explores these melting barriers, their implications and the power of learning more from individual observations.

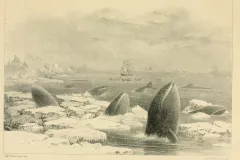

Already, whales from the different ocean basins have been seen on the opposite sides of the world, as well as a variety of seabird species. For example, bowhead whales, which use their large heads to break up sea ice, from the two different ocean basins converged in the Northwest Passage during the summer of 2010 to feed in the same location. Gray whales, which aren’t able to push through ice like bowhead whales, are currently found in the North Pacific. In the spring of 2010 a gray whale was observed off the coast of Israel—the first sighting of this species in the Atlantic for over 200 years. Additional observations of gray whales followed in 2013 off the coast of Namibia. Seabirds, which typically need access to water in order to feed on fish, aren’t able to traverse the Arctic where thick sea ice restricts their access. With melting Arctic ice, seabirds like the Northern Gannet have been observed for the first time in history on islands off the coast of California—far from their North Atlantic home.

That’s where you come in.

Movements of large numbers of marine mammals and birds from the Pacific to the Atlantic, or vice-versa, will not occur overnight - most of the observations of these movements are still anecdotal—a gray whale here, or a gannet there. But Seabird McKeon, a research biologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and lead author of the paper, wants citizen scientist observers to know that “Your observations are important and appreciated by people who are paying attention as well.”

These individual observations of small changes, while not necessarily statistically significant on their own, can be combined to help tell the story of how climate change is playing out in the Arctic. The questions posed by these animal movements range from how well the animals will be able to survive in the new environment, to how their presence could impact commercially important or endangered species.

“All citizen science starts with observation—people out there sharing what they see,” McKeon emphasizes. As they accumulate, stories of the changes will begin to come together like puzzle pieces to provide a clearer picture of what is happening. If enough observations of species moving between ocean basins are made and recorded, the anecdotes can reveal larger scale patterns of change, which can then be combined with other information.

The fossil record and genetics can help tell us when species that are currently separated between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans may have last interacted. Computer models and some creative thinking can help point out the future challenges that species may face in a new home, answering questions about what they will eat and where exactly there is habitat that meets their needs. Gray whales, for example, feed on mud shrimp that bury themselves in the Pacific’s muddy seafloor. If their populations begin to spend time in the Atlantic, what might they forage on? McKeon speculates—possibly the commercially important blue crab that can be found buried during winter months at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Although not in the paper, these are the types of changes that might have to be considered in the face of an uncertain future.

Climate change can feel both overwhelming and far removed from our day-to-day lives, but these small changes are happening all around us. What are now scattered sightings from birders or beachgoers could soon contribute to a global picture of how life on Earth is changing along with the climate. The more informed about these changes we are, the better prepared we will be to face them head on with solutions to the problems that will inevitably arise.

If you’re interested in documenting change, here are some ways you can currently learn more and share information: