Anglerfish Lure Prey Throughout the Ocean

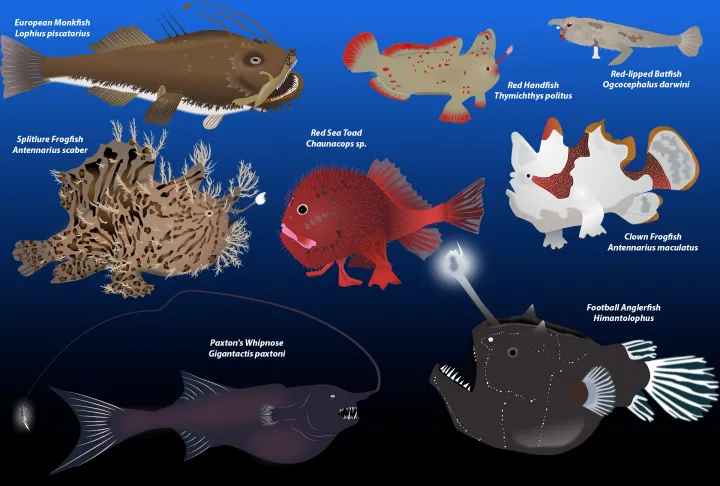

The grumpy frowns and bulging eyes of anglerfish are unmistakable. But undoubtedly their most distinguishable trait lies atop their head: an extended, sometimes glowing lure. This is how they attract a meal in the otherwise deep, dark sea. These deep-sea anglerfish are the most recognizable, but the anglerfish as a group are much more diverse than commonly known. Anglerfish and their close relatives, frogfish, handfish, batfish, sea toads, and goosefish (Lophiiformes) live all around the world—some live in the deep sea, while others swim in shallow waters. Within these areas, they are mostly found along the seafloor, with some in open waters. These fish exhibit a wide variety of interesting adaptations that visually set them apart from many other fish species—including their close relatives. However, they all share something in common: their lure.

The lure is the most recognizable trait of the anglerfish that sets them apart from thousands of other fish. Called an esca, the lure often serves as a way for them to attract food. In deep-sea anglerfish, the lure glows a faint blue light. Created by symbiotic glowing bacteria called Photobacterium take up residence in the anglerfish’s esca, and in exchange, the bacteria gains protection and nutrients as the fish swims along. For anglerfish that live in shallower water, the lure attracts prey in numerous ways. In batfish, the lure releases a chemical that helps with capturing prey, while in frogfish, the lure resembles shrimps or worms—a tricky deception to target small, hungry fish.

This lure has a remarkable evolutionary origin. Most fish have a dorsal fin atop their head that aids the fish in swimming. For anglerfish, the dorsal fin serves another purpose. Over millions of years, the front elements of the fin have evolved into luring apparatus. The lure is a modified fin ray. Anglerfish have evolved a complex muscular system that allows the modified fin ray to quickly move, jerking and wiggling the esca to attract prey into the fish’s gaping maw. Additionally, most anglerfish are “gape-and-suck” feeders, using strong, specialized lower jaws to create a suction that pulls prey into their mouths. These and other adaptations have made anglerfish a voracious predator.

The anglerfish are very diverse. In order to understand the diversity of these species, you must first understand taxonomy (the way organisms are classified). This system starts broad, and then narrows down based on shared characteristics and relatedness. Lophiiformes is the order, or the broad grouping, that includes all anglerfishes. Smaller families, genera (the plural of genus), and then species are nested within the order. Let’s explore some of the anglerfish families and the species within them.

Deep-sea Anglerfish

(Ceratiidae and Himantolophidae)

Deep-sea anglerfish are perhaps the first image that comes to mind when you think of an anglerfish. It’s almost something out of a nightmare—a bulbous body and needle-sharp teeth, the epitome of a deep-sea horror. However, deep-sea anglerfish come in many shapes and sizes—with 200 species in this group, there’s a lot more diversity than you might think. The Humpback anglerfish (Melanocetus johnsonii) or Pacific footballfish (Himantolophus sagamius) are some of the species in the family that fit the typical description of an anglerfish, but there are plenty of other species in the Ceratioidei suborder that stray from the classic look. For example, the wolftrap anglers have longer bodies and a protruding upper jaw, while the horned lantern fish (Centrophryne spinulosa) has a bulbous head and thinner body.

Deep-sea anglerfish exhibit sexual dimorphism, or different characteristics in males and females. Deep-sea anglerfish exhibit extreme differences—the male is significantly smaller, being fully grown at only a couple of centimeters. This drastic difference plays a role in the reproduction of these fishes: some deep-sea anglerfish exhibit parasitic reproduction, a method where the male will latch on to the female for the entirety of both of their lives. As time passes, the male slowly fuses into the female’s body until he has become a permanent appendage. The lure is also only found in female deep-sea anglerfish. Males don’t need to hunt, instead providing the female with sperm in exchange for nutrition. This permanent relationship allows female deep-sea anglerfish to ensure all of her eggs are fertilized.

Sea Toads/Coffinfish

(Chaunacidae)

It’s not surprising how sea toads got their name: this anglerfish’s rotund body and wide, downturned mouth make it appear more toad-like than fishy. But that’s not all—this species can walk. Sea toads have modified fins which they use to move about the seafloor.

Most sea toads are a shade of red, spanning from bright crimson to pale pink. They are found along continental slopes in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans. Though they are bottom-dwellers living in an environment with very little light, their lures don’t glow like their open-water relatives. Sea toad lures are short and small—it’s unlikely that prey could even see their esca in the first place. It is hypothesized that sea toads instead use chemicals to attract prey, but with little known about sea toad biology, scientists still aren’t quite sure.

Frogfish

(Antennariidae)

Frogfish are masters of disguise. Living in tropical and subtropical waters, these fish blend right in with their surroundings through their impressive coloration and camouflage. Frogfish are scaleless; with some species appearing to be almost hairy, with long, feathery protrusions called spinules jutting out from their bodies. Other species have rough bumps making them indiscernible from some types of coral or sargassum. However, blending in with the environment isn’t the only visual trickery frogfish utilize—their lures also exhibit mimicry. In many species, lures resemble worms or fishes. The hunter becomes the hunted when the frogfish’s prey realizes that its tasty snack is in fact a trick, having been drawn right in front of the frogfish’s mouth. Like sea toads, they have modified fins that allow them to walk—this is their preferred method of moving, having rarely been seen swimming.

Handfish

(Brachionichthyidae)

This appropriately named family is characterized by oversized pectoral fins resembling hands. Like many other anglerfish, handfish use these fins to walk rather than swim. Instead of a typical lure, the handfish’s modified dorsal fin is fused to the second and third dorsal spine, forming a crest. There are only fourteen species of handfish, all native to Australia and Tasmania. Unfortunately, these species are facing a conservation crisis—eight of the fourteen species are endangered, having been impacted by fishing, coastal development, and pollution. Despite their bright coloration, these fishes are difficult to spot due to their small size.

Batfish

(Ogcocephalidae)

Batfish, like many other lophiiforms, are found at the bottom of the sea. Their flat, circular or triangular bodies and long tails make them almost look more like a ray. Though mostly living in tropical and subtropical deep waters, batfishes have been observed in shallow coastal waters and river estuaries. Batfish have modified pectoral fins used for walking and an esca that excretes a liquid chemical to draw prey in close. When not in use, these fishes can withdraw their lures into a small cavity in their heads.

Perhaps the most recognizable species of batfish is the Red-lipped batfish (Ogcocephalus darwini). Native to the Galápagos Islands, this species has a bright red mouth that resembles lips.

Goosefish/Monkfish

(Lophiidae)

To the untrained eye, a goosefish may appear to be a stretch of sand with a long, wide mouth. But look closer, and you’ll see two beady eyes and a protruding lure. Native to the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, these creatures wait pressed along the seafloor and use their lure like a fishing line. After drawing their prey near, goosefish open their gigantic mouths and gulp up their prey once they are within reach. Goosefish eat invertebrates and fishes but have also been known to gobble up seabirds. Reaching a maximum size of six feet and about 75 pounds, it’s no wonder they have an insatiable appetite. Like many other anglerfish species, they use their pectoral fins to slowly amble about the seafloor. Goosefish will also use their fins to dig themselves a hole in the sand where they can camouflage themselves, waiting for the perfect moment to lurch up and ambush their prey.

___________________________________________________

Editor's Note: Danielle Olson contributed to the writing of this article