Fish Fins that can Taste

Flounders are odd-looking fish. With eyes seemingly squashed together on one side of their face and a contorted mouth, they appear to be creation’s careless mishap rather than an evolution shaped for advantage. But flounders adapted precisely for a life dwelling along the seafloor. A flattened body allows for seamlessly blending into the seafloor, and both eyes atop the head help to survey the surroundings. Now, scientists have discovered another marvel of their contorted biology—a special probe on the fish’s underside covered in taste buds. Careful examination of the probe’s anatomy reveals it evolved from a fish fin.

The special probe, also known by scientists as a gustatory stalk, is found on the underside of the Remo flounder (Oncopterus darwinii). It sits near the flounder’s mouth and is shaped like a miniature arm with a bulbous club at the end; a bend towards the end acts like a joint. Along either side of its length is a fringe of filaments called fimbriae. As the flounder swims along the seafloor the stalk plows into the sand with its head in search of food.

Examination of the stalk’s muscles by researcher Paulo Presti, a Smithsonian-associated researcher at the University of São Paulo in Brazil, confirmed previous studies of the bones that showed the stalk originated from the dorsal fin. Much like the anatomies of whale flippers, bat wings, and human arms, which all share similar bones and muscle structure, the anatomy of the flounder’s gustatory stalk shares bone and muscle structure with a normal fish dorsal fin. Over millions of years small adaptations transformed the fin into the sensory appendage. Today, it sits on the underside of the flounder and has shifted toward the front of the head.

Flounders do not begin their life looking like a Picasso creation; their transformation from symmetrical fish to a lopsided bottom feeder created an ideal circumstance for part of the dorsal fin to become a sensory appendage. Larval flounders appear just like any other fish with a symmetrical body plan and eyes on either side. As the larva matures it begins its metamorphosis. The bones in its face reshape as one eye migrates to the other side. The eyeless side then loses its coloration. And the dorsal fin, once in the middle of the body on the larva’s back, partially shifts to the underside. Now in contact with the seafloor, the front portion of the fin no longer serves a purpose as swimming aid. Instead, this part of the fin is adapted.

New research by Presti indicates the sensory stalk is covered in highly adapted taste buds. While studying the anatomy of the stalk, Presti noticed a large nerve not normally found connected to the dorsal fin. Further investigation showed that it connects to the brain in the place where taste nerves originate.

“When I spotted that nerve, I started going through its path to see which nerve it would be,” says Presti. “And I saw this particular nerve that, according to the to the literature, innervates only taste buds.”

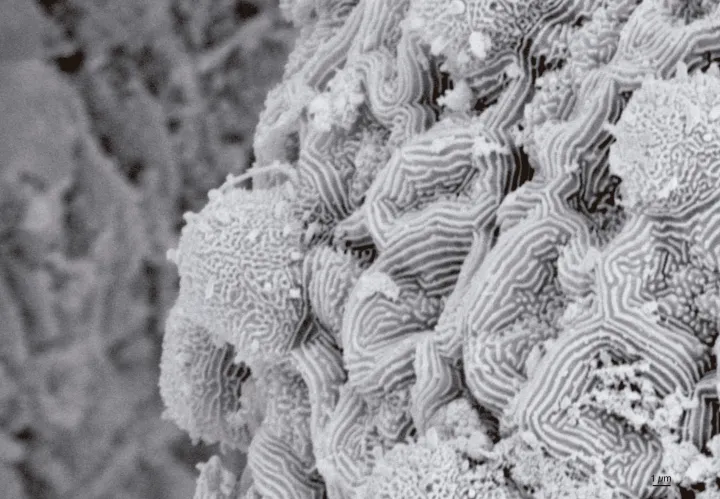

That discovery prompted Presti to take a closer look at the modified dorsal fin. Many fish have primitive taste buds on their fins. Life in the open ocean means food or danger can appear from any angle; above, below and from either side. To stay aware of their surroundings, some fish use sensory cells on their fins to have a better sense of the world around them. Sure enough, an inspection under the microscope revealed ridges of taste buds covering the arm of the stalk. Additionally, there were goblet cells, a type of cell that secretes mucous, which protect the taste buds against damage and disease. With eyes on the top of its head, the Remo flounder appears to rely on the sensory stalk to probe into the seafloor sand to seek out food.

“It's like an x-ray vision to see what's beneath the sand and search for food,” says Presti.

It’s a remarkable adaptation; a change from a fin that allows for swimming to a digging probe that can taste. Without being able to observe the transformation, it can seem almost fantastical. But millions of years of small adaptations molded the Remo flounder into the fish we see today.

And it’s not the only example of a dorsal fin that has evolved to serve another purpose. The lure atop the anglerfish’s head is a modified dorsal fin. As are the remora sucker disks that help the fish adhere to the underbellies of sharks. In the deep sea the tripod fish sits upon the seafloor atop stiffened tripods that evolved from fish fins. Along with the Remo flounder’s stalk, these are the ingenious ways fish have adapted to their unique and extreme environments.

A face like a flounder is easy to label as grotesque. Perhaps, now with a greater understanding of their marvelous transformation and the discovery of their fin-turned-tongue, the fish can earn some credit. They may not be pretty, but they are a marvel just the same.