The Great Pacific Migration of Bluefin Tuna

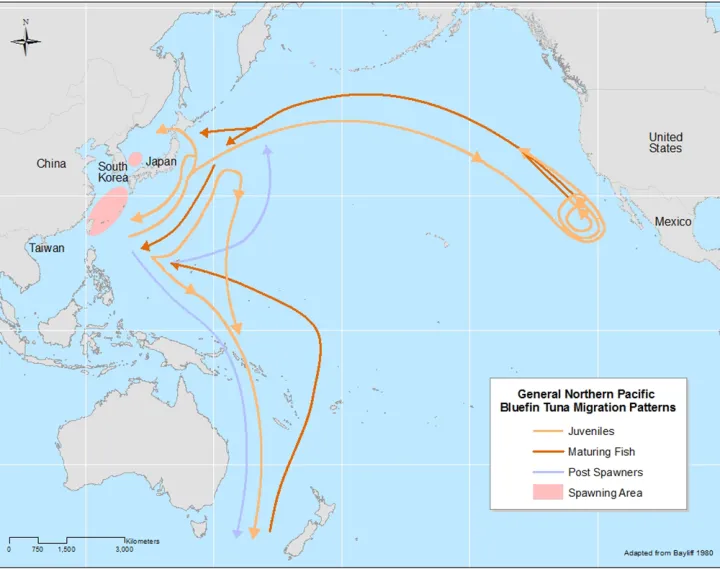

Shortly after their first birthday, Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) complete an impressive feat. From the spawning grounds in the Sea of Japan where they were born, the young tuna embark on a journey over 5,000 miles (8,000 km) long, across the entire Pacific Ocean to the California coast where they spend several years feeding and growing. Until recently, scientists believed only a small portion of juvenile tuna made the journey, but several new studies show that may not be the case—in some years the majority of tuna aged between one and three participate in the trans-Pacific migration.

To get to California, the fish traverse through icy, Arctic waters that sometimes reach temperatures close to 9 degrees Celsius (about 16 degrees Fahrenheit). That’s pretty chilly, even for a fish. But like the closely related Atlantic and southern bluefin, Pacific bluefin tuna have a few special adaptations to help them navigate through the cold water. As one of the few warm-blooded (or endothermic) fish, bluefin tuna retain the heat they produce as they swim. Most fish lose a lot of their body heat as the warm blood circulates through the gills. The thin capillary walls in the gills are perfect for the blood to pick up oxygen, but they also leave the blood exposed to the icy temperatures of the water. For a bluefin, that’s not a problem. Their specialized blood vessel network, also known as a counter-current heat exchange system, aligns the warm veins leaving the muscles right next to the cooler, incoming arteries so that the heat is passed from the veins to the arteries in an efficient loop. The heat stays in the muscle and never gets the chance to be sapped away in the gills.

Once the young tuna reach the shores of California they will remain there for several years, traveling up and down the coast between Mexico and sometimes as far north as Washington State. By the time the tuna reach age seven many return to the Western Pacific to spawn off the coast of Japan.

This migration is a pretty amazing feat, but the Pacific bluefin tuna population is seriously struggling. It may seem like a minor detail, but the fact that more tuna make the trans-Pacific migration than previously thought has huge implications for managing the fishery. A high demand for tuna to supply the sashimi industry means there is extraordinary fishing pressure on the species. Sushi chefs and restaurant owners pay significant money for the fresh fish—at the famous Tsukiji market in Tokyo, a single tuna was sold for 1.8 million dollars in 2013. Although buying at such an outrageous price is more of a marketing scheme to attract new bluefin-eating restaurant customers than a true representation of demand, there is little doubt that the appetite for tuna has taken its toll. Scientists from the International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species (ISC) estimated in a 2016 report that only 2.6 percent of the original, pre-fished population remains, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates the population is 25 percent of what it was in the 1950s when the first population data was recorded.

If a high number of Pacific bluefin live their early lives off the coast of California, any catch limits enforced by the United States and Mexico will also impact how many tuna live long enough to swim back to Japan to spawn. Tuna caught by fishermen in the Eastern Pacific, on the West Coast of North America, will never have the chance to reproduce and help the population rebound.

Currently, a serious debate on whether to list the Pacific bluefin tuna as an endangered species, rather than the current threatened designation, is underway. And there is a glimmer of hope for the species—in September 2017 international leaders from countries that fish the tuna agreed to a goal of reaching 20 percent of the Pacific bluefin’s historic population by 2034.

So, the next time you are tempted to order a tuna sushi roll, think of its herculean effort to swim across an entire ocean and the challenges these fish face to survive. Currently, the Monterey Seafood Guide and Marine Conservation Society FISHONLINE recommend avoiding all Bluefin tuna—the Albacore tuna is a better choice. Perhaps, a little time and space are just what the Bluefin need and our decision to let them be is the key to their survival.