The Origin of Eels

Slithering, slimy, and brown, the European eel is not the most charismatic nor charming aquatic creature. It may not bring about ideas of mystery or intrigue, yet its existence has plagued scientists with questions for millennia. With its many life stages, its biology is truly vexing. But perhaps the biggest mystery has been tied to just where all eels set out for when they head toward the ocean via coastal streams and rivers at the end of their lives. Through the efforts of a team of scientists it is a mystery no more. In 2022, researchers finally tracked a group of migrating eels to the middle of the Atlantic Ocean in an area known as the Sargasso Sea.

The mystery of the eel can be traced back to ancient times when the Egyptians told of how the eels sprang up from the Nile at the warming of the sun. For thousands of years, it was the consensus that eels were the exception in the animal kingdom and could bypass the rules of procreation and spontaneously rise from the river mud. There was no greater promoter of this theory than Aristotle, who, after immense study of their anatomy, proclaimed that they came from within “the entrails of the earth” since they seemed not to have any sex genitalia and therefore could not procreate through sex. Pliny, the Elder of Rome, had his own thoughts and believed baby eels sprung from the particles shed by adult eels as they rubbed their bodies on riverbed rocks. Generation after generation of scientists continued to be stumped, until finally, in the 1890s scientists observed the last metamorphosis of an eel into its sexually mature state—with sex organs glaringly present.

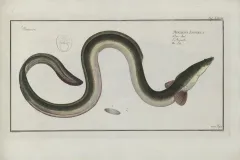

The life cycle of the eel includes several metamorphoses from a larva to a mature eel and is the reason for much of the confusion in the scientific community. Each life stage is so different from the next, they were once mistaken as different species, and today each stage is identified with its own name to specify which one is being discussed. After hatching from an egg in the ocean, the leptocephalus larval eel is swept across the ocean in the Gulf Stream. It is only millimeters long, with a tiny head and a see-through body— very different in appearance from its adult forms. The larvae’s journey takes several years, and during that time, it slowly grows by feeding on tiny bits of marine debris and phytoplankton. By the time it gets to the shores of Europe it makes its first metamorphosis into a glass eel, which then travels up rivers, seamlessly transitioning to a freshwater life. This is when it makes the next transition to a young eel, or elver, and then two years later to a yellow eel, a muscular fish with the ability to go dormant in cold seasons and slither across land to find new bodies of water to call home. The eel will spend most of its life as a yellow eel, and this is the most familiar life stage for people living in coastal and riverine areas. Then as if on some hidden cue, a yellow eel will transform into the sexually mature silver eel and make its final migration back out to sea.

Though scientists had seemingly solved the mystery of the eel and its reproduction by the early 1900s through the discovery of its sex organs, no one knew where they went to procreate. The eels disappeared into the ocean, and aged larval eels appeared near the shores. The question remained, where did they go?

The first inkling that the eels might be traveling to the Sargasso Sea came from the herculean efforts of Danish zoologist Johannes Schmidt. From 1904 to 1921 (with a five-year break for World War I) Schmidt tirelessly trawled the ocean to find the larvae and by extension the birthplace of eels. Starting from the shores of Europe he discovered that only the largest larvae, those around two to three inches in length that were closest to turning into glass eels, inhabited the coastal waters. He needed to expand his search. As he moved west, the larvae continued to get smaller, and it was through this trial and error that he found himself in the middle of the Atlantic with larvae so tiny “that there can be no question…where the eggs were spawned.”

It would be 100 more years until confirmation of Schmidt’s discovery that adult eels migrated to the Sargasso Sea to lay eggs. Between 1921 and 2022 the understanding that eels travel to the Sargasso Sea was based on knowledge about the larvae—that’s where the smallest larvae are, therefore, it must be where they hatch. No spawning eels nor eggs had ever been found there. Then, in 2022, came a breakthrough.

Satellite tagging, a technology that allows scientists to track animals via satellite through the placement of a tag, finally became advanced enough in the mid-2000s to be applied to the mystery of the eel. In 2018 and 2019, 26 female eels were tagged off the coast of the Azores right before they were to embark on their migration. A year later, five arrived in the Sargasso Sea, which led to a major scientific publication in 2022 announcing the discovery. The eels did indeed make a 3,000 – 6,200 mile (5,000 – 10,000 km) migration across the Atlantic Ocean, the second longest recorded migration of a bony fish.

Scientists have yet to observe a mating in the wild, which will likely be the next great eel mystery to solve, but the discovery of adult eels in the Sargasso Sea is a tremendous milestone. Since the 1980s the European eel has experienced a 95 percent decline in its population, putting it on the critically endangered list. The decline is attributed to multiple issues, including dam building, disease, illegal trade, and climate change, and the latter likely influences life stages that live in the ocean rather than during its freshwater life stages. Frustratingly, this is the stage scientists know about the least. If history is any indication, the eel will continue to inspire the most determined scientists, and perhaps with a little determination we can unravel the remainder of their secrets in time to save them.