Scientists Catalog Life on the Island of Moorea

Introduction

Welcome to Moorea, a tiny, isolated island in the middle of the vast Pacific. Moorea is 132 square kilometers (51 square miles) of tropical ecosystems – from jungle and wetlands to beaches and coral reefs – with no major landmasses for thousands of miles. While it may look like the perfect vacation spot, it’s actually the site of intense fieldwork by a team of scientists determined to understand the island’s natural history in more detail than ever possible before--an effort known as the Moorea Biocode Project. When completed, the researchers’ detailed catalog (or biocode) will represent a first for humankind: an entire tropical ecosystem surveyed and described down to its most fundamental element, the DNA in its organisms’ cells.

Research & Exploration

No Stone Unturned, No Reef Unexplored

Imagine trying to catalog every living thing in your backyard. Where would you begin? How could you be sure you found every insect and plant, every tiny burrowing critter and every bird in the sky? Now imagine doing the same thing for an entire island – and the waters around it. That’s exactly what researchers with the Moorea Biocode Project are attempting. Divided into teams, the researchers fan out across the island from mountaintop to seafloor to collect one of every life form big enough to pick up with tweezers. By the end, they expect to have collected specimens, taken photographs, and completed DNA identifications (“barcodes”) for between five and ten thousand species. The tally is growing daily, and the results will allow them to examine questions about changes affecting the whole globe, like sea-level rise and invasive species.

Scientists

Dr. Chris Meyer, Professional Bio-Scavenger

Dr. Chris Meyer has an obsession with collecting. A Smithsonian scientist, Chris has followed his passion to remote places around the globe, including Moorea, where he leads a team of scientists in a race to catalog every living thing big enough to pick up with tweezers.

As a kid, Chris Meyer filled his closet with shoeboxes of baseball cards, sand from various beaches, anything that indulged his “hyper-active collector gene.” Now, as a Smithsonian scientist and the Director of the Moorea Biocode Project, Chris has turned his hobby into a full-time job collecting and studying marine life in spectacular places like Moorea. Chris’ work is helping to document marine biodiversity, figure out how ecosystems function, and predict how they will respond to change. These are big issues to tackle, because in most of the ocean, the more you look, the more life forms you find. “I see it as a kind of huge scavenger hunt,” Chris says. “It’s very rewarding to pursue questions you are curious about.”

Tools & Technology

An Island Under the Microscope

After each scouting trip, researchers return to the Gump Field Station where they record, preserve, and study what they have collected. In addition to microscopes and cameras, the scientists use cutting edge technology to extract and analyze their specimens’ genetic material. By sequencing, or reading the chemical code written in a particular segment of an organism’s DNA, the researchers can identify a unique marker – called a “DNA barcode” – for each species. Like barcodes on items in the store, these markers allow scientists to accurately group members of the same species or tell when similar-looking individuals are actually two different species. This is important both for cataloging life on the island and for understanding how species interact – who eats whom and which strange looking larvae grows up to be which familiar adult.

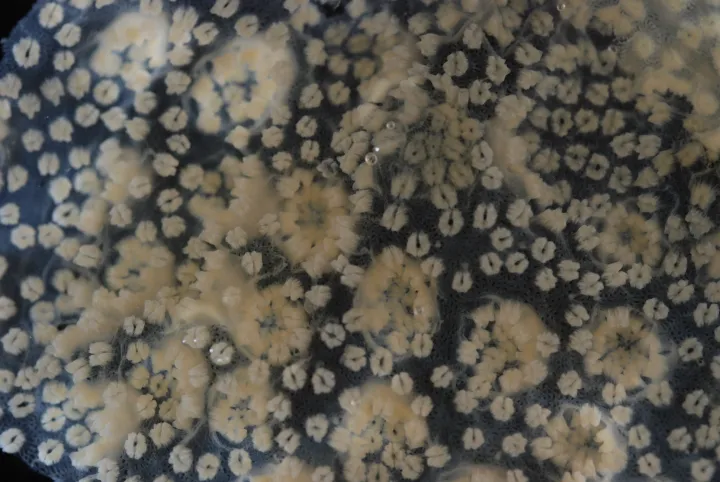

Naked coral?

Well, not exactly. “Stony” corals like this piece of Pocillopora (or cauliflower coral), normally have rigid skeletons, but researchers used chemicals to dissolve this specimen’s skeleton in the lab. Getting a tissue sample from coral for DNA analysis can be hard work using a hammer and chisel, but this new technique allows scientists to expose the “naked” tissue without breaking a sweat.

Collections

Why do taxonomists—scientists who study living things and how they are related—need all those neatly preserved specimens in vials and jars? Find out how specimens collected in Moorea record a permanent snapshot of the island’s natural history and how they might be used in the future.

In the Field

Packrats with a Purpose

Glance around the lab at the Gump Field Station in Moorea and you’re likely to see stacks of algae fronds pressed neatly in newsprint or vials of tiny crabs preserved carefully in alcohol. Why in the age of digital photography, databases, and DNA sequencing do scientists in this remote location bother to save these specimens once they glean their data? Are they simply packrats? Actually, “voucher specimens,” as they’re called, are critical to our understanding of the natural world. Being able to return decades later to the original specimen that was used to describe a new species or to a group of individuals that was collected in a certain location can help settle an identity crisis or answer questions about changes in an organism’s range. While DNA barcodes are very useful tools, data sets can never entirely take the place of the real thing.

Permits Obtained

Please note that the scientists working on Moorea – and elsewhere around the globe – obtain permits to collect organisms and are careful not to disturb wildlife or the surrounding environment more than necessary to gather the samples they need. In other words, please don’t try this at home.