Summer in a Sub: DROP Down to Discovery

You never know where following your passions can take you. I came to the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) two years ago as a research intern after graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in biology. I never expected, two years later, to spend a summer working with scientists, sub pilots, and engineers to help document the biodiversity of marine life off of Curaçao, a small island in the southern Caribbean, just north of Venezuela.

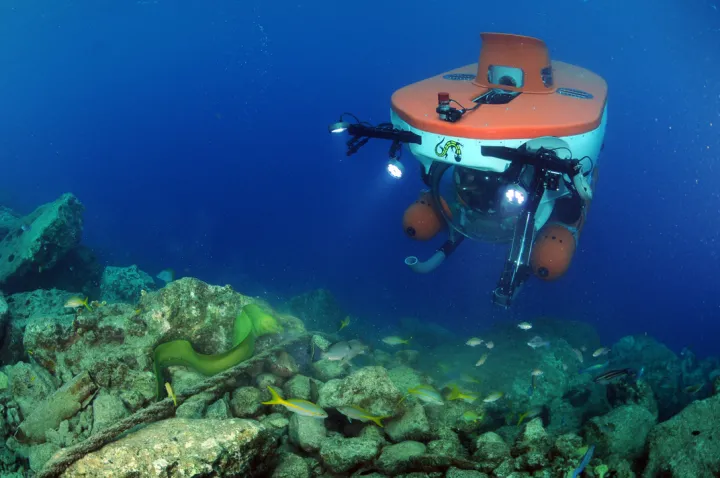

I arrived in Curaçao with the first group of Smithsonian biologists involved with the Deep Reef Observation Project (DROP). Researchers from NMNH and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama are here to collect and study marine life. From using our hands to collect algae and dip nets to collect fish near the surface, to using the Curasub -- a five-person submersible with hydraulic collecting arms that can reach organisms at depths of about 300 meters (about 1,000 ft) -- we knew our mission would take a variety of tools and expertise to complete.

Smithsonian curator of fishes, Dr. Carole Baldwin leads the first team. Her use of modern molecular tools, like DNA barcoding (using a short sequence of DNA to help identify species), combined with traditional morphological techniques (looking at physical structures), has already led to the discovery of many new species of shallow-water Caribbean reef fishes.

This is a particularly well-studied area of the world’s ocean. If we’re finding new species here, it’s incredible to think about what we might find elsewhere, especially since it’s estimated that more than 95% of the livable space on Earth is in the ocean. Needless to say, we were all anxious to get in the sub and start exploring!

I prepared for my first sub dive with a safety briefing and a final run to the bathroom (a very important thing to remember!). I climbed down into the sub with my field notebook and flashlight, Carole and Dr. Ross Robertson from STRI followed. Finally, the technician controlling the collecting arms and sub pilot came down and closed the hatch behind them. We were ready to descend.

As we descended, I was amazed by the changing scene outside the sub’s window. In the shallower depths, I saw lots of familiar corals, fish, sponges, and anemones. But as we went deeper, things began looking a bit unfamiliar.

Going down, the colorful reefs were replaced by rocky walls and slopes covered in silt and rubble. As we looked for signs of life, I saw the depth gauge read 155 meters and I realized we were well beyond where one could snorkel or scuba dive. Although there was over 500 feet of water above us (about the height of a 40-story building), all I could think about was what we would discover below us. We collected several specimens on our first trip, including a 60mm cave basslet (Liopropoma mowbrayi) and a 35mm candy basslet (Liopropoma carmabi) both caught at a depth of 91 meters (300ft). You’ll hear about collecting in one of our next posts.

Three hours later we surfaced and took the specimens back to the lab to be identified, photographed, and preserved for archiving in the museum’s collections. Relatively new additions to the collections are the physically small, but tremendously important, tissue samples we take from every specimen for DNA analysis. Being in a sub is an amazing experience, but knowing that the specimens and tissue samples we collect will be available for future generations of scientists around the world to study is pretty incredible too.

As a young biologist, I am thrilled to be working with Smithsonian scientists studying a variety of marine organisms: from fish and crabs, to algae and urchins. Over the next five weeks, the scientists will post blogs and videos about their findings in Curaçao. You’ll hear about the challenges of collecting with a 5.5 ton submersible; interesting crustaceans found on a wood fall at 244 meters (800 ft); and about “living fossils” found in the deep sea. We hope you will check in on us and share in the excitement as we “DROP” down into this world of discovery.