Tough Teeth and Parrotfish Poop

What goes in must come out in some form, and with parrotfish, what comes out is sand.

As the name might suggest, these tropical fish, with their big beaks and bright colors, look like their land-based counterparts. Parrotfish live in coral reefs and spend their days chomping down on coral. Hard coral is no match for the large beak of the parrotfish, which researchers have recently found is formed by some of the strongest teeth in the world.

Parrotfish chew on coral all day, eating not only the hard calcium carbonate skeleton, but the soft-bodied organisms (called polyps) that cover the skeleton and the algae (called zooxanthellae) that live inside them and provide the coral with energy, as well as bacteria living inside the coral skeleton. When parrotfish poop out the coral they eat, the soft tissues are absorbed and what remains comes out as sand-a lot of sand. In a year, one large parrotfish can produce 1,000 pounds (450 kg) of sand, the weight of a baby grand piano.

Each parrotfish has roughly 1,000 teeth, lined up in 15 rows and cemented together to form the beak structure, which they use for biting into the coral. When the teeth wear out, they fall to the ocean floor. This isn't a problem for the parrotfish, though, because another row of teeth is right behind the first, just waiting to chow down on coral.

Biophysicist Dr. Pupa Gilbert has known she wanted to study parrotfish teeth for a while.

"I'm a scuba diver, and I've always heard how loud they are underwater, when they crunch coral" she said. No one had measured just how hard, stiff, and tough these teeth are, so Dr. Gilbert got to work.

What she and other researchers from Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory and the University of Wisconsin - Madison found when they looked into the composition of parrotfish teeth was an intricate crystal structure. Parrotfish teeth are made of a material called fluorapatite which contains calcium, fluorine, phosphorous and oxygen, and is the second-hardest biomineral in the world. Fluorapatite scores a five on the Mohs' hardness scale, making their teeth harder than copper, silver and gold. No biomineral in the world is stiffer than the tips of parrotfish teeth. The teeth can also withstand a lot of pressure. One square inch of parrotfish teeth can tolerate 530 tons of pressure-equivalent to the weight of about 88 elephants.

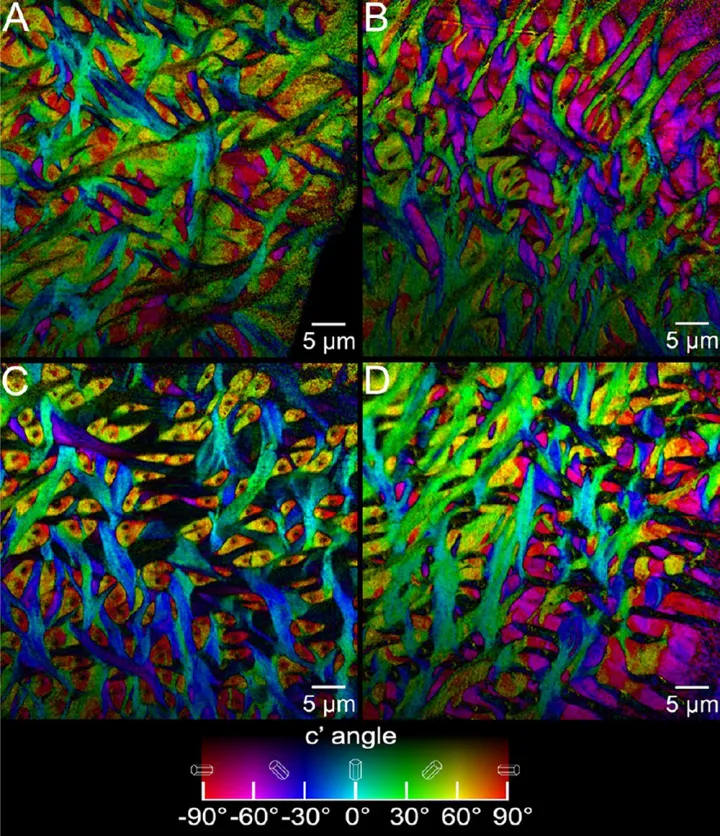

The team developed a tool in order to see the orientation of the crystals in the fluorapatite, called PIC mapping, and the Advanced Light Source. This technology essentially takes pictures of the crystals, which are ordered stacks of atoms. It color-codes the measured orientations of the crystals, and creates a picture that looks a little bit like abstract art, but can tell the scientists a lot about the structure of the teeth.

When Dr. Gilbert and her team found this structure, they were surprised.

"It's totally exciting; fantastically beautiful," she said.

The structure of parrotfish teeth was one the researchers had never seen before, with the crystals oriented in interwoven bundles, which form a chainmail pattern. The specific structure is one that could be mimicked to create abrasion-resistant moving parts, but Dr. Gilbert is much more interested in the research possibilities of the PIC mapping technology and what new structures she may be able to find. Next on her list: a closer look at human teeth and bones using the tool.

While Dr. Gilbert does this, parrotfish continue to go about their days, almost constantly grazing on coral. While parrotfish eat a lot of coral, they also eat the algae that grow on top of coral reefs. This cleaning function is important to the reefs' ecosystem survival. When the fish eat the algae that compete with the coral polyps, the coral is able to grow and is more resilient in the face of local stressors (like pollution or warming). In areas where overfishing has wiped out parrotfish populations, coral reef ecosystems are not as productive, and cannot sustain as much diverse life.

If you enjoy gazing at colorful coral, or making sandcastles on the beach, you have the strength of parrotfish teeth to thank.