Why I Love Polychaetes

Polychaete worms are not your average cringe-inducing, writhing worms. (Okay, maybe some are.) They are fascinating, varied, and a critical part of our ocean.

The visual variety among the more than 10,000 described species means a polychaete enthusiast is never bored. They come in every imaginable color and pattern, from completely transparent to iridescent to candy striped. You can find polychaetes of every shape from spherical to sausage-shaped to pencil thin, and every size from microscopic to several feet long. Some are smooth and sleek, others frilly and elaborate. They are numerous and diverse throughout the ocean from the mud of the deepest trenches, hot vents, the wide open expanse of the midwater, coral reefs, kelp forests, mud flats, tide pools and even to freshwater habitats.

Polychaetes are critical members of all ocean food webs. Some are voracious, jawed predators; others are delicate filter feeders, scavengers, farmers, symbionts, or even bone-eaters. These sometimes beautiful, in many cases tiny, and often abundant animals play a crucial role in structuring and oxygenating the sea floor, much like their earthworm cousins on land. Many build tubes for protection and with these tubes they build reefs, provide homes for numerous other animals, and stabilize shifting sediment.

I saw my first polychaete while diving in Pohnpei, Micronesia. A college student, I was there for a year to teach high school and jumped in the water whenever I wasn't in the classroom. Every time I donned the diving mask my dad gave to me when I was SCUBA certified in a nearly-frozen Midwestern lake, the immense diversity of shapes, sizes and colors of the animals living on the reefs, in the water, and in the sand blew me away. Even then, the delicate, sensitive, colorful Christmas tree worms that sprung from coral fascinated me—my first introduction to the polychaetes.

My next memory of polychaetes was as a Master's student. We scraped algae off of a floating dock and took it back to the lab to see what we could find. I was ecstatic to finally be learning about all these amazing animals, which were so different from those I knew from playing in woods, streams and lakes as a kid. While sorting the material from the dock I found a small worm with incredible appendages waving in every direction, with bold stripes and several pairs of obvious eyes. Its fine control over all those waving bits and pieces as it explored the petri dish mesmerized me.

When my professor said, "Don't worry about identifying that. It's a polychaete; they are too difficult," I took it as a challenge. I managed to identify it as Trypanosyllis gemmipara, a species belonging to the family Syllidae, an amazing group of polychaetes with more than 700 named species and probably as many still to be named. This observation was the first step in solidifying polychaetes as my favorite group of animals, and one that I still enjoy working on today. Their variety and beauty hold my fascination like no other group.

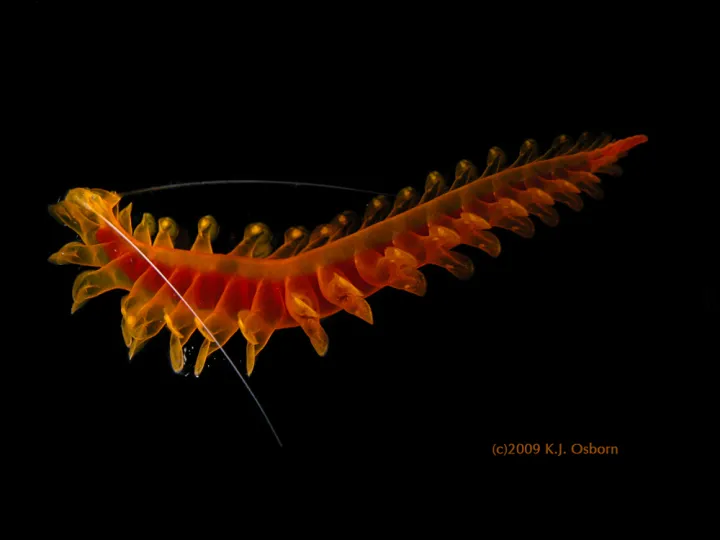

My favorite polychaetes have to be those belonging to the family Tomopteridae. These beautiful, gelatinous worms live their entire lives in the open expanse of ocean called the midwater. They lack the many bristles for which polychaetes are named (poly: "many;" chaete: "bristles"), but they make up for this loss with large fleshy paddles that allow them to swim gracefully and with incredible speed and agility. Tomopteridae can be completely transparent or have gold, orange, red or purple ribbon-like guts. This color sometimes transfers to the body, and I've seen some gorgeous bright red polychaetes with gold accents (like the image on the left). They range in size from a few millimeters to nearly two feet long. Like many of the animals thriving in the ocean's midwater, very little is known about them. We don’t know what they eat, or how and why they produce gelatinous, spherical egg cases. We don't know the use for the pair of suction cup-like appendages on their heads, or why they are the only marine animals that produce yellow bioluminescence.

Today, on the first-ever International Polychaete Day, we celebrate the many varieties of polychaete worms and their contributions to our planet. We also celebrate a great polychaetologist, Kristian Fauchald. Kristian passed away in April of 2015 and is missed by many marine biologists for his generous personality, stories from the field, and extensive knowledge of polychaetes. Kristian never flagged in his enthusiasm for polychaetes in the 58 years he studied them.

I inherited the NMNH Polychaete collection from him when I arrived at the Smithsonian in 2011, and had the great pleasure of having an office next door to his. I loved bringing back new specimens from my deep-sea expeditions and sharing my discoveries with him. His eyes would light up at the strange things I found before he launched into stories from his years of polychaete science and discovery. I hope you are as fascinated with these animals as I am on this first International Polychaete Day—there’s still so much to find out about them.

Editor's note: The first International Polychaete Day is July 1, 2015. Find out about events near you! See more beautiful polychaete images!