You Light Up My World!

While people may give chocolates to the ones they love on Valentine’s Day, some animals pull out the fireworks and devote a whole light show to attracting potential mates.

Meet Photeros annecohenae, a species of ostracod that lives in shallow seagrass habitat in the western Caribbean Sea. Males of the species create a beautifully complex bioluminescent courtship display, emitting flashes of blue in the water during the night in hopes of enticing a female.

Ostracods are tiny (from less than a millimeter to a few millimeters long), flattened shrimp-like creatures that live in what looks like a miniature clam shell. Several species possess a special gland (called the light organ) that allows them to create light by producing chemical compounds. This form of light production is called bioluminescence.

Luminescent ostracods can use light for predator defense and for courtship displays. Those that use light to surprise and deter predators emit light when threatened or even when swallowed, causing predators to spit them out in order to avoid being spotted by their own predators.

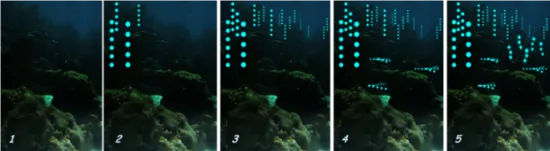

In some species, like P. annecohenae, bioluminescence is also used for mating displays, but only by males. Like fireflies on land, males of each species employ a distinct patterns of light pulses (seen as a string of dots) that attract only females of the same species. Just as a fireworks show takes place during the night when the brilliance of light can really wow the audience, P. annecohenae’s courtship display is performed nightly in absolute darkness when males have the best chance of being spotted by females.

In the case of P. annecohenae, males show off just how dazzling they can be by performing little dances in which they emit short bursts of light as they move toward the surface of the ocean. They initiate their “dance,” which lasts an average of 45 minutes, with a stationary phase, in which they produce short (second-long or less) pulses of bright blue light, catching the attention of potential female mates. Then, in the next phase males, spiral vertically up the water column creating more rapid flashes of light that are less bright.

If a male is successful and an interested female approaches, the male grabs onto his newfound partner with his antennae and the pair will mate. Competition is tough—often the brightest male will gain the attention of a female, but males also can impress by synchronizing their lighting display with other males or sneaking up and “stealing” a mate from a fellow male.

One can imagine how all these courtship displays together can form a larger luminescent display against the black backdrop of the nighttime ocean. Attracting others with a flashy dance seems to have worked rather well for the species, so next time you are out on the dance floor, think about adding some glow sticks or standing where the disco ball hits you just right!

Special thanks to Jim G. Morin, Gretchen A. Gerrish, and Trevor. J. Rivers for providing resources and images.

This post first appeared on the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, Department of Invertebrate Zoology "No Bones" Blog. Written by Maria Robles Gonzalez and edited by Liz Boatman.