A Dive into Dolphin Data: The History of Bottlenose Dolphins in the Potomac River

Dolphins may seem like unlikely visitors to the Potomac River, an urban waterway running from West Virginia through Washington, D.C. and into the Chesapeake Bay. But since 2015, researchers have identified over 2,000 individual dolphins swimming in these waters.

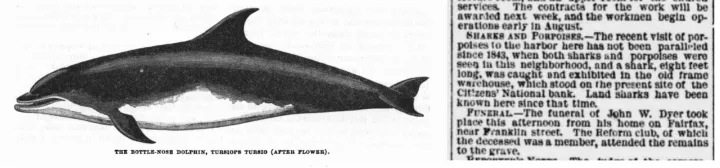

The first reports of dolphins in the Potomac date back to the 1800s, when Smithsonian biologist Frederick True documented fishers seeing dolphins near Quantico, Virginia and newspapers reported locals seeing them near Alexandria, Virginia and Georgetown, D.C. For over a century, these were the only accounts of dolphins in or near the District available to scientists. During this period, the river became so overrun with sewage, algae, and garbage that former President Lyndon B. Johnson declared the river “a national disgrace” in 1965.

Since 2015, scientists have started observing bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops erebennus) in the Potomac once again. But whether these marine mammals have been in the Potomac River all along, or are suddenly returning to the area after a long period away, is not yet known. Scientists at Georgetown University and Duke University aim to answer this question through the Potomac-Chesapeake Dolphin Project (PCDP), which seeks to understand the behavior, population dynamics, and distribution of bottlenose dolphins and inform protection efforts. The researchers track how many dolphins visit the Potomac River and middle Chesapeake Bay, how often they come, and how long they stay.

Dr. Janet Mann gets to the bottom of this question by climbing aboard a “tiny little tin boat” at the mouth of the Potomac and getting up close with the dolphins. Mann gets to know each individual dolphin, whom she names after important U.S. historical figures — these dolphins include Bill Clinton and Zachary Taylor. She tracks the dolphins’ individual behaviors and group movements throughout the year through visual observations. While watching the mammals, her collaborator, Ann-Marie Jacoby and another graduate student, Melissa Collier, saw a mother give birth in the Potomac in 2019, an event that has very rarely been witnessed.

Dr. Mann’s team cannot single-handedly observe and identify every one of the 2000 plus bottlenose dolphins identified in the Potomac and middle Chesapeake. To strengthen the research force, the University of Maryland relies on “citizen scientists” — individuals who report their dolphin sightings through the DolphinWatch app, launched in 2017. The app is intended to be user-friendly, requiring individuals only to provide an email, location of their dolphin sighting, and a brief description of the event. According to Jamie Testa, the DolphinWatch coordinator, scientists then validate these citizen-sourced findings with other approaches such as underwater acoustic devices that record underwater sounds, including dolphin clicks.

These approaches reveal that there is a large dolphin presence in the lower Potomac and greater Chesapeake region. But whether the dolphins were always here, or whether they recently returned, remains unanswered. According to Mann, the common assumption that the number of dolphins is increasing is not necessarily true. “People assume that the number of dolphins is increasing, but it’s probably because we’ve been publicizing dolphins being in the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay. We don’t really know,” Mann says.

To get to the bottom of this question, Jacoby, a Ph.D. student at Duke University and associate director of the Potomac-Chesapeake Dolphin Project, decided to dedicate her Ph.D. research to figuring out the historical occurrence of dolphins in the Potomac. Jacoby combs through old newspapers and talks to fishers (locally known as “watermen” and “waterwomen”) who might know more about the past presence of dolphins. Jacoby has found that while scientific studies undertaken prior to the initiation of the Potomac-Chesapeake Dolphin Project didn’t find dolphins in the Potomac, they have been reported in newspapers and seen by fishers throughout the river since Frederick True’s time in the 1800s.

One possible reason for the scarcity of dolphin data in the past century is that scientists may have missed what was in front of them due to misconceptions about the dolphins. Unlike a typical residential bottlenose dolphin population that stays in one place, these dolphins change their location depending on the season, and are only observed in the Potomac and middle Chesapeake between April and October. This atypical pattern in presence may have led researchers to miss the dolphin populations in previous years.

Another hypothesis for the apparent increase in bottlenose dolphin population size in recent years is a resurgence or bounce-back from a viral outbreak in 2013. The virus — called cetacean morbillivirus — caused an unusual mortality event that was first identified in the Chesapeake Bay. According to this reasoning, once the virus subsided, more dolphins may have come to the Bay because there was less competition, allowing the dolphin population to experience a resurgence.

Scientists are also considering the idea that human actions impact the presence or absence of dolphins in the Potomac and Chesapeake region, and that recent improvements in animal protections may have led to an increase in the dolphins’ prevalence. Both the river and the bay had a troubling history of pollution, with the bay being declared one of the earth’s first marine “dead zones” in the 1970s. However, legislation such as the Clean Water Act of 1972 and the establishment of the Chesapeake Bay Commission in 1980 vastly improved the water quality. A cleaner bay could result in a higher abundance of prey species for the dolphins to feed on, which in turn supports larger dolphin populations.

According to Jacoby, there is not yet enough data to tell which, if any, of these explains the current distribution of dolphins in the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay. Ongoing studies, including the citizen science initiative through DolphinWatch, will contribute to finding this out. “We need to have evidence,” Jacoby says. “Without that, you can’t say for certain whether or not a trend is happening.”

While these historical questions are still up in the air, the knowledge that dolphins currently visit the Potomac can already inform protection efforts. In fact, with the knowledge of dolphins in the region, nearby military facilities have begun including bottlenose dolphins in their environmental impact statements.

According to Jacoby, “What I really want to get out of this is filling in a knowledge gap so that these animals are better protected.”