A History Entwined: Vaquita, Totoaba, Fishermen

The Vaquita is a small, elusive, and critically endangered marine mammal that is endemic to a small area of the upper Gulf of California. Its population is plummeting and heading for extinction--at the current rate of population decline, the vaquita may be extinct in a few years.

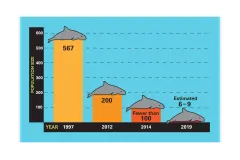

The vaquita’s population before 1997 is unknown, but genetic evidence indicates it was never abundant. The documented decline from 1997 to 2012 was largely due to vaquitas being caught in shrimp gillnets. Since 2013, vaquita populations have drastically declined as the increased black market demand for a rare fish (called the totoaba) has escalated illegal gillnet fishing.

Vaquitas are unintentionally caught in gilllnets set to illegally catch totoaba fish for their highly prized/priced swim bladders, which are sold through organized crime networks to markets in Asia. Conservation efforts have not been effective and have sometimes been opposed by local fishing communities that have not been provided with viable, vaquita safe fishing methods or alternative livelihoods.

Overlapping social, political, economic, and environmental concerns collide in the history of the vaquita porpoise and the totoaba.

For another look at the vaquita story, check out this slideshow of images.

Banner Image Credit: Paula Olson, NOAA, Photo taken under permit (Oficio No. DR/488/08 SEMARNAT)

Illustration Credit: Rachel Ivanyi

Intensive fishing of totoaba begins and expands throughout upper Gulf of California.

Swim bladders sold in China and U.S.; totoaba meat appears on U.S. tables.

Totoabo swim bladders are sold today on the Chinese black market for traditional medicine and cosmetics. Credit: Earnest Tse / Alamy

Gillnets and motorized boats allow fishermen to catch entire spawning aggregations of totoaba.

Vaquitas first seen by fishermen as bycatch.

Bycatch is when marine life, such as the vaquita, unintentionally are caught in fishing nets set for a target species, such as the totoaba. Credit: Christian Faesi, copyright by Omar Vidal

Mexico’s local fishing industry and income take a drastic economic hit because of environmental issues.

New programs subsidize local fisheries and promote regional tourism.

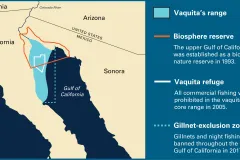

Mexico establishes regional biosphere reserve.

Eliminating gillnets is key to protecting the vaquita from extinction.

Illegal totoaba fishing surges in pursuit of highly prized swim bladders smuggled to the U.S. and China.

Vaquita refuge established. Mexico bans gillnet fishing permanently, but uncontrolled fishing for totoaba continues.

Fishing for the endangered totoaba was banned in 1975. Since 2013, black market demand for the totoaba’s swim bladders has skyrocketed. Credit: Omar Vidal

Vaquita mothers with healthy calves spotted, but many illegal fishing vessels also seen in protected habitat.

Governments and environmental organizations continue to monitor the vaquita population, advocate for better law enforcement, remove abandoned fishing gear, develop vaquita-friendly fishing practices and provide incentives to stop using gillnets. Credit: Paula Olson, NOAA, Photo taken under permit (Oficio No. DR/488/08 SEMARNAT)