From Mermaids to Manatees: the Myth and the Reality

In centuries past, the ocean was thought to be full of krakens, sea serpents, sea monsters and other fantastic creatures. They helped to bring the mysterious ocean into the more familiar realm of the ‘known' by introducing human traits and an element of storytelling. One creature that shows up in such stories throughout history is the mermaid.

Mermaid mythology is quite varied, with mermaids taking on many different appearances, origins, and personalities. The first recorded half-fish, half-human creature is Oannes, a Babylonian god from the 4th century BCE who would leave the sea every day and return at night. Though the ancient Greek sirens, who lured sailors to their deaths in Homer's Odyssey, were originally described as having bird bodies, they are often portrayed as fish-tailed mermaids—so frequently that variations on the word “siren” means mermaid in many languages. Although these sirens had vicious personalities, as did the mermaids in J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan, some versions of mermaids can be kind, such as Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, made famous by Disney’s 1989 popular film iteration of the same story.

Mermaids are just characters in stories, of course. But in a world saturated with mermaid mythology, people sometimes think they see them in real life. When Christopher Columbus set out to sea in 1492, he had a mermaid sighting of his own; little did he know that this encounter was actually the first written record of manatees in North America. It might seem strange to confuse a slow-moving, blubbery sea cow with a beautiful, fish-tailed maiden. Yet it’s a common enough mistake that the scientific name for manatees and dugongs is Sirenia, a name reminiscent of mythical mermaids. Even today there are false mermaid sightings. After a fake documentary special on mermaids aired on Animal Planet in 2013, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration was flooded with calls from people asking for the truth about mermaids. (The truth is that mermaids are entirely fictional.)

While mermaids hold much of our attention and affection, their real-life doubles are left struggling in the sea. Manatees are easily injured or killed due to their large size and generally slow pace, which makes them vulnerable to being hit by motorboats and caught in fishing nets. Another threat to manatees is blooms of poisonous algae, which can grow rapidly during warm summers, especially in areas with nutrient pollution from fertilizer runoff. Some types of algae produce a toxin that contaminates the manatees’ wetland and estuary habitat and sticks to the seagrass they eat, making manatees sick or even killing them. Unusually cold water in the winter can also kill many manatees.

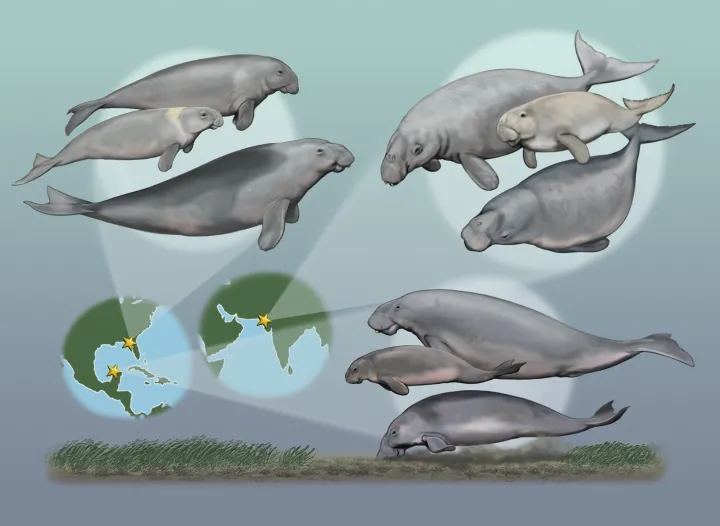

With all of these factors combined, manatees are suffering. Florida manatee deaths hit a record high in 2013, with 829 killed—about 17 percent of the known population, including 126 calves. Of these, 276 were killed by algae blooms, 115 from an unknown disease, and 72 from boat collisions. Because of such harrowing statistics, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed all three species of manatees as vulnerable to extinction, and a few manatee subspecies as endangered. One subspecies, the Antillean or Caribbean manatee (Trichehus manatus manatus), currently has a population of just 2,500 mature individuals and is expected to decline by more than 20 percent over the next two generations unless something can be done to reduce these threats. There is also trouble for dugongs, close relatives of the manatee that share many of the same threats. The IUCN lists the dugong as vulnerable, as it is extinct or declining in at least one-third of its range.

If we don’t take actions like slowing boaters and reducing fertilizer runoff, we may lose these creatures, and a source of mermaid myth will vanish from the ocean.