North Atlantic Right Whale

Introduction

Stretching up to 16.8 meters (55 feet) long and weighing up to 62 tons (70 tons), the North Atlantic right whale is one of the world’s largest animals—and one of the most endangered whales. Scientists estimate that between 300-400 individuals remain. Why so few? For generations, the right whale was hunted for oil and baleen. Today, collisions with ships and entanglements in fishing gear are the two biggest threats for the whales with about 58 percent of deaths occurring due to entanglement. Some scientists fear that right whales could become extinct within 20 years. To prevent that from happening, scientists are using a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect and rescue right whales.

Life & Natural History

Meet not only the North Atlantic right whale but also some other fascinating members of its family tree—past and present. Travel back to the times when whales walked on land and the mighty, serpent-like Basilosaurus prowled the seas.

Diversity

Teeth or Baleen?

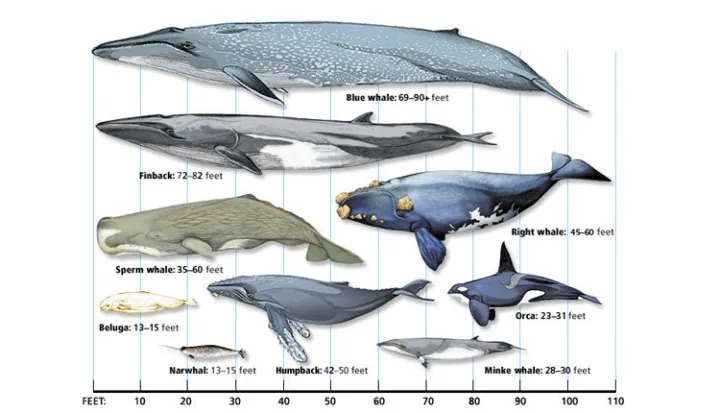

Over many millions of years, whales evolved into two major groups—those with teeth (Odontoceti), and those with baleen (Mysticeti). Right whales belong to the second group. They are among the largest of the baleen whales, which also includes blue whales and humpbacks. Baleen whales filter food from the water through sieve-like plates of baleen. There are three species of right whales living in different parts of the world: North Atlantic (Eubalaena glacialis), Pacific (Eubalaena japonica), and Southern (Eubalaena australis). Along with other whales, dolphins, and porpoises, right whales are cetaceans—one of the major groups of marine mammals.

Species Ecology

Seasonal Migrations

Most North Atlantic right whales head south for the winter, to the shallow coastal waters off the southeastern United States. That’s where the females give birth to calves—a single calf every 3-5 years. In spring the whales migrate north. They spend the summer and early fall months feeding and nursing their calves in the waters off New England and the Bay of Fundy. Where do the whales breed? Scientists are still trying to find out. North Atlantic right whales live at least 70 years—and possibly as long as 100 years.

Evolution

From Sea to Land, Land to Sea

Whales are vertebrates—animals with backbones. The very first vertebrates were fishes, which evolved in the sea. Amphibians made the transition to land, evolving and diversifying into many kinds of vertebrates, including mammals. Among these mammals were the ancestors of whales. Over time, the ancestors of whales moved from land back to the sea, taking advantage of its rich food supplies. As early whales adapted to their new marine surroundings, a diversity of species evolved.

Science

So what are scientists doing to protect the remaining right whales? Everything they can think of including taking pictures from airplanes, attaching radios to whales’ backs, listening underwater for their comings and goings…and much more.

Research

Keeping Track of Right Whales

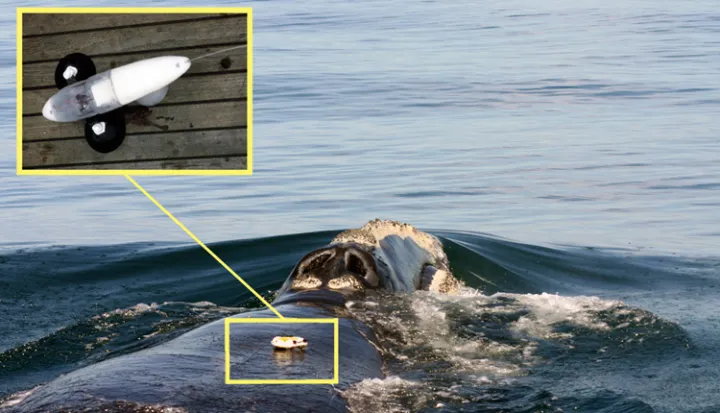

One way researchers keep track of North Atlantic right whales is by taking photos from ships and airplanes. They examine the images closely for identifying marks such as the pattern of callosities on their heads. They try to identify individuals by matching the images with other photos in the North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog. Records of these sightings provide diaries of individual whales. Researchers also track right whales by attaching electronic tags to their backs. Despite this careful monitoring, some whales disappear each year to unknown locations. Others suddenly reappear, often after a decade’s absence. And some young whales just show up unexpectedly. How can researchers lose track of a huge whale for years at a time? Whales may be big—but the ocean is bigger.

Collections

Marine Mammals at the Smithsonian

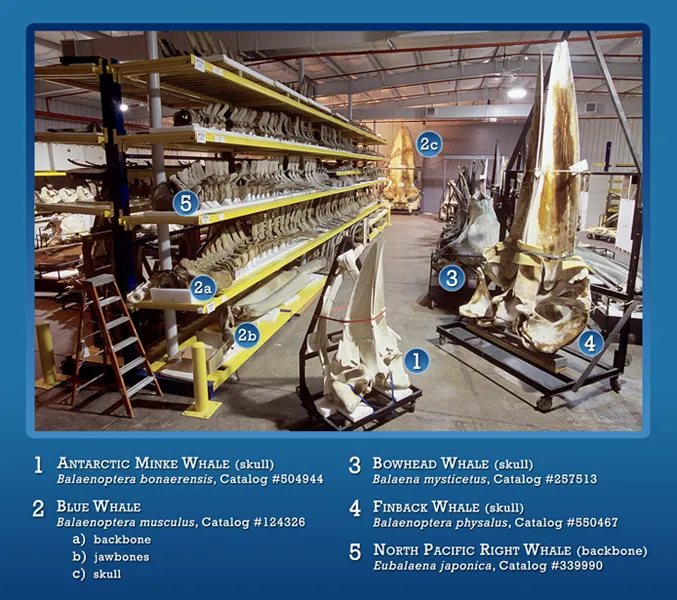

The Marine Mammal Collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History is the world’s largest. It includes more than 6,500 specimens of cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises), 3,100 specimens of pinnipeds (fin-footed mammals like walruses and seals), and 380 specimens of sirenians (manatees and dugongs). Most species are represented by bones and skeletons. But the collection also includes a fairly large number of preserved specimens.

Technology

Listening for Whales

Scientists are using a variety sophisticated technologies in an effort to help right whales survive—including sound. Since 2008 a network of 13 detection buoys has been listening for right whales round-the-clock in the crowded shipping corridors of Massachusetts Bay. Software on each buoy records and analyzes underwater sounds up to 5 nautical miles away. When the software detects the call of a right whale, it sends a message to staff at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. They, in turn, alert ships in the area to slow down and watch out for whales.

Protecting Whales from Fishing Gear

Commercial fishing gear can pose a major threat to right whales. As they feed, the whales sometimes get entangled in lines attached to gear at the ocean bottom. Every year about 50 North Atlantic right whales become entangled in fishing gear and about 83 percent of all whales have had at least one entanglement encounter. New types of fishing gear have been developed to diminish this danger. They include buoy lines with “weak links.” These lines automatically release when pressure is applied, preventing whales from becoming entangled. But despite these changes, the whales are still struggling to avoid gear. Since 2009, 58 percent of whale deaths are due to fishing gear entanglements, an increase from the 25 percent between 2000 and 2008. A network of scientific organizations has also been instrumental in coming to the aid of right whales that may have gotten entangled in fishing gear.

Scientists

Learning from Dead Specimens

Animals that died as the result of beach strandings, accidents, and other causes form the only means of learning about the anatomy and life history of more than half of all whale species. So when researchers in the Marine Mammal Program at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History are presented with a dead whale specimen, they extract all the biological data they possibly can from the remains. Curator of Mammals Dr. James Mead and Collection Manager Charles Potter examine many dead whales—as well as porpoises and dolphins every year. They used their in-depth knowledge of whale anatomy to help develop the right whale model of “Phoenix” that serves as the centerpiece of the Smithsonian’s Sant Ocean Hall.

Human Connections

Why were right whales considered the “right” whale to hunt for so many years? What threats do they face today? Do these critically endangered whales have a fighting chance?

Cultural Connections

Native Whalers

For thousands of years, Native peoples living in the Arctic and along Alaska’s coast relied on whales for food, fuel, and bone. To ensure bountiful harvests, they honored and gave proper thanks to whales in a variety of ways. This carved box is one example. It stored harpoon blades during whale hunts. “Living” inside the box was meant to give the blades spiritual powers to carry a harpoon back to the blade’s “home” in the whale.

Hunting Whales for Profit

Centuries ago, harpooning whales was a way to get rich. A single right whale could yield 5,247 liters (1,386 gallons) of oil plus 293 kilograms (647 pounds) of baleen. Among the most successful hunters of North Atlantic right whales were the Basques of Iberia (Spain). They started hunting whales in western Europe in the 11th century and continued until whales there were depleted. Basque whalers then moved across the Atlantic to Labrador, where from 1520 to 1630 they hunted right and bowhead whales along migration routes. By the 1600s those whale populations, too, had plummeted. So the Basque fishermen turned to cod and seal.

Threats and Solutions

A Future for Right Whales?

It has been illegal to hunt right whales since 1935. Then why are there so few of them? Right whales face a variety of threats today. Because of their large size and slow movements, they are vulnerable to colliding with ships and becoming entangled with fishing gear. They may also suffer from pollution, degraded habitats, and declining prey. Every year scientists revise their estimate of the number of right whales still alive. The population peaked to about 483 whales in 2010, but since then the population has again been on the decline. But the number is so small that scientists cannot reliably predict the population’s future size. More troubling is that females are more likely to die than males, potentially because of the extra burden of pregnancy that makes them more susceptible to other stresses. Today, females are giving birth every 9 years (compared to every 3 years in the 1980s), a rate that is too slow to keep the species alive. Without intervention, scientists predict the population may disappear in the next 20 years.