Seals, Sea Lions, and Walruses

Introduction

Flippered and charismatic, pinnipeds (which includes seals, sea lions, and walruses) are true personalities of the sea. Like whales, manatees, and sea otters, they are marine mammals, meaning millions of years ago their ancestors evolved from a life on land to a life at sea. Today, they remain creatures of both land and sea. Though able to walk on land, they are truly at home in the water. Strong flippers and tails propel them and a streamlined body helps them cut through the water efficiently.

It’s easy to tell the enormous, tusked walrus from other pinnipeds, but seals and sea lions are easy to confuse. The easiest way is to look at their ears—sea lions have small ear flaps while seal ears are nothing but small holes.

Are You An Educator?

Anatomy, Diversity, and Evolution

Life at sea requires a powerful and streamlined body. Pinnipeds have adapted sleek, torpedo-shaped bodies that can cut through the water without producing significant drag. They’ve also developed powerful flippers to propel and steer themselves through the water. Unlike whales and dolphins, sea lions have extremely flexible bodies, and can almost bend their bodies in half.

Anatomy

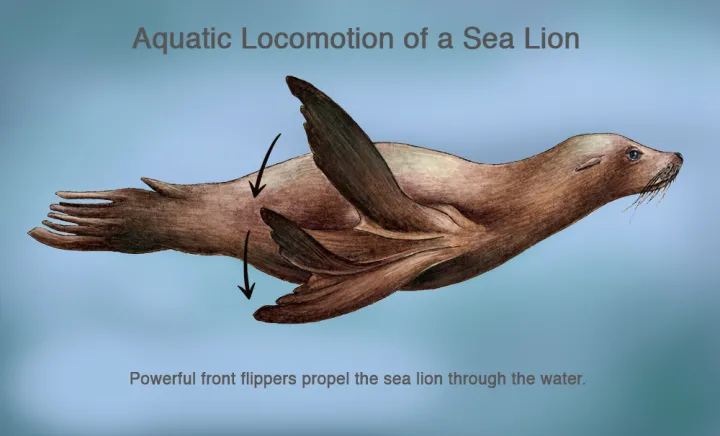

Propulsion and Movement

Though able to move on both land and sea, pinnipeds are the most efficient underwater. Some species spend the majority of their life in the ocean—female northern elephant seals spend 66 percent of their time in the open ocean.

Despite looking similar, seals and sea lions propel themselves through the water in different ways. For the sea lion, swimming is all about the front flippers. In a sweeping motion, they stretch their long flippers out to the side and then quickly tuck them into their body to form a torpedo-like shape. Scientists refer to this motion as a “clap.” Sea lions are the only aquatic mammals that swim this way. Seals, walruses, whales, otters, and others rely on the back end of their bodies—their tail—to produce thrust. Instead, the sea lion tail is used like a rudder. By using their front flippers, sea lions are easily the fastest group of pinnipeds. Most pinnipeds cruise at speeds around 5 to 15 knots, though sea lions sometimes reach bursts up to 30 knots.

When traveling long distances, sea lions are known to employ a swimming technique called porpoising. As the sea lion dashes across the sea surface it breaches the surface in a series of consecutive leaps. This technique is likely used to increase their speed, since air resistance is significantly less than the drag of water. Seals, too, have key adaptations that make them efficient swimmers, like lots of blubber to make them buoyant. When at sea, northern elephant seals spend 85 to 95 percent of that time underwater and make massive migrations up to 13,000 miles long.

Diving is part of life for pinnipeds, and even for sea creatures they are impressive divers. The Southern elephant seal has been recorded at 2,388 m, a dive that lasted for two hours, though on average their dives are around 20 to 30 minutes at a depth of 270 to 550 meters. They accomplish this by both decreasing their heart rate to below resting state and by constricting their peripheral blood vessels to keep blood near important organs. When resting, a seal’s heart will beat at about 100 beats per minute, but when diving it can slow to as low as five beats per minute. Seals also have about twice as much blood as humans when body size is considered, and their blood can carry about three times the amount of oxygen as human blood. Not only do seals use hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying molecules in human blood, they also have a second molecule in their muscle tissue called myoglobin that also carries oxygen. Upon surfacing, it takes seconds for pinnipeds to resupply their bodies with oxygen. With every breath they obtain about 90 percent of the oxygen inhaled—humans only capture 20 percent.

Oxygen deprivation is only one obstacle when it comes to diving—pressure is also a problem that seals and sea lions have successfully worked around. Increased pressure that is greater than the atmosphere forces nitrogen gas into the blood, but as pressure decreases (during an ascent) that same nitrogen will turn back into gas. If nitrogen were to dissolve into blood during a dive it could lead to the formation tiny gas bubbles during the ascent. When humans dive this can cause the bends, but pinnipeds have evolved to avoid such a devastating event. Right before a dive, pinnipeds will exhale all the air out of their lungs, an act that ensures nitrogen gas cannot dissolve from the lungs into the blood. As they dive their lungs shrink and fold until essentially flat—no air is left inside. They also have flexible rib bones that bend rather than break under intense pressure.

Constant diving and a life far out to sea also means seals need to get creative when it comes to finding time for sleep. Elephant seals sleep during their deep dives. As they drift downwards the seals enter a "sleep spiral" so they can catch up on sleep during months-long feeding trips. Dives are so deep that they can take up to 30 minutes to reach the deepest depth, and during that time they can enter a deep sleep up to 10 minutes. At depth the seals are less likely to encounter predators, enabling them to sleep soundly without fear of harm. Remarkably, when the seals get low on oxygen they awaken in time to return to the surface.

On land, seals and sea lions also have different methods for getting around. Sea lions, fur seals, and walruses are able to rotate their rear flippers up and under their bodies so that they can waddle on all four flippers. This enables their agile movement and balance on land. Seals, however, cannot do this and instead shimmy on their bellies. Traveling requires the back and forth shift of weight from their upper body to their pelvic region, almost like a caterpillar. Although they may seem clumsy, seals are quite speedy and can travel fast enough on land to overtake a human.

Salt Water

Pinnipeds that live in the sea must rely on freshwater to survive. Special adaptations help them retain as much freshwater as possible. Most freshwater comes from a pinniped’s meal—Harbor seals obtain about 90 percent of their freshwater from the fish they eat. Once the food is ingested, pinnipeds retain the water for as long as possible. Pinniped kidneys are especially efficient at retaining water, therefore, pinniped urine can be saltier than the surrounding seawater.

Staying Warm

Water absorbs heat 25 times faster than air, and for warm blooded animals like pinnipeds this means that they need an efficient way to retain heat. Pinnipeds have devised several ways to combat the cold. Notably, pinnipeds are chubby animals. In general, marine mammals are larger than mammals on land, an adaptation that minimizes the area of skin in contact with the water. Elephant seals and Walruses can weigh up to 4 tons, and even the smallest seals are notably rotund. Pinnipeds also rely on a thick layer of blubber to keep them warm. Up to 50 percent of a seal’s weight can come from its blubber reserves. This is especially true during the breeding season when seals stock up in anticipation of caring for a newborn pup.

For species living in the extreme cold, fur adds an additional layer of warmth. Fur seals rely on two layers of fur, an outer protective layer and an underfur that traps air bubbles and insulates the skin—the seals have roughly 300,000 underfur hairs per square inch. Baby harp seals have an extra defense to keep warm—their snow-white fur helps absorb heat from the sun.

Sometimes, however, pinnipeds need a way to cool off. A special network of blood vessels help to move blood to different areas of the body—called counter-current heat exchange. At times when a pinniped is too warm, blood is brought to the skin and to the flippers, where it is exposed to the cold water or air. When the pinniped is too cold this system runs warm blood from their inner bodies out to their extremities next to the cold blood running back inwards. The two blood temperatures participate in heat exchange and, therefore, the cold blood is warmed before re-entering the body core. Since walruses lack fur, the rushing blood to the extremities causes the skin to turn a rosy red hue.

Senses

Many aspects of the senses of pinnipeds also reflect their sea-going habits.

VISION

Pinnipeds need to see both above and below the sea surface, a slight dilemma since good eyesight in either location requires very different adaptations. Terrestrial animals, including humans, rely on the cornea—the clear outer layer of the eye—to focus images using a property called refraction, a bending of light as it crosses through different materials. As light travels through the air and enters the eye, it bends to the appropriate angle and creates a focused image on the retina. Underwater, terrestrial animals become farsighted because the fluid of the eye and the water are too similar, the light doesn’t bend enough so the image doesn’t focus effectively. Pinnipeds solve this issue with an especially round fisheye lens that refracts light appropriately underwater. Humans, on the other hand, have a flat lens.

Having acute vision underwater means that on land a pinniped is nearsighted, especially in low light. When in bright sunlight, however, the pupil contracts, allowing only a pinhole for light to enter the eye. This limited area decreases how effective the cornea and lens are at refracting light (the mechanism that makes vision underwater clear) and helps focus vision in air. Additionally, pinnipeds have a crystal structure in the back of the retina that reflects light back through the retina a second time, effectively doubling the amount of light captured by the eye.

TASTE

Pinnipeds gulp their food whole, which may be why they have a very limited sense of taste. One study showed that a sea lion had an altered gene responsible for detecting sweetness, meaning they cannot taste sweets. They also lack umami taste receptors that detect savory taste.

TOUCH

Covering the faces of pinnipeds are whiskers called vibrissae. These hairs are extremely sensitive to touch, and can even detect sound vibrations. Using their vibrissae, pinnipeds can determine the shape of an object placed in front of their face and detect extremely subtle water movement. Pinnipeds rely on their vibrissae when hunting for food. When fish swim through the water their undulating fins leave a wake in the water and the vibrissae are sensitive enough to detect the trail back to the fish.

HEARING

As pinniped ancestors made the transition from land to sea they needed to adapt to a life both underwater and on land, and this includes hearing. Hearing all comes down to the perception of vibrations, and underwater sound vibrations cause the entire skull to vibrate, not just the membranes in the ears. This is why sound underwater sounds garbled to humans. Pinnipeds have the extra challenge of needing to hear well in both air and water. They have massive ear bones and the ability to close the ear canal when underwater. Pinnipeds scan their head side to side to help them pinpoint the source of a sound.

SMELL

Underwater, pinnipeds have no sense of smell, but on land scent plays a big part in day to day life. Scent is used as an alert mechanism when predators (like humans) are nearby and as a way for males to determine whether a female is ready to mate. Scent is also an important way for mothers and pups to bond. When mothers leave their pups to forage for food they must rely on their pup’s unique scent as a way to find them among all the other pups.

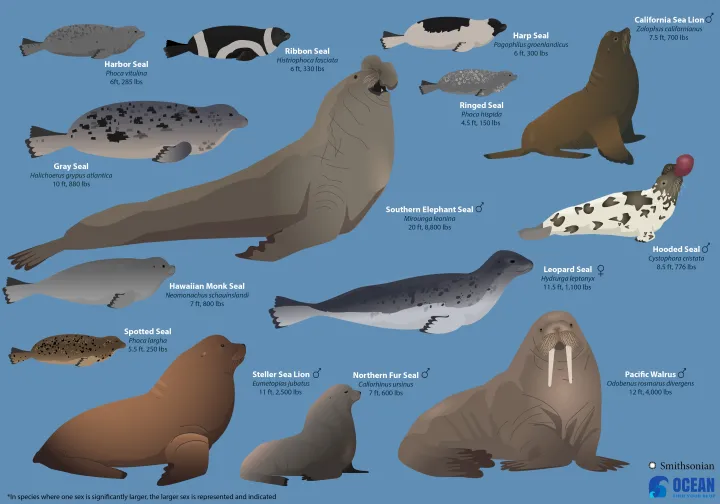

Diversity

Pinnipeds include the families Odobenidae (walrus), Phocidae (true seals), and Otariidae (fur seals and sea lions). Today, there are 33 species. Some species exhibit sexual dimorphism, meaning the two sexes look distinctly different from one another. In many cases the male is also significantly larger than the females. Their closest relatives are the bears, weasels, racoons, skunks, and red pandas.

True Seals

Across the globe there are 19 species of seal. Most are ocean dwellers, living in places spanning from the Arctic, to the tropics, to Antarctica. The Baikal seal, however, lives in a landlocked lake in the middle of Asia and is the only seal to live exclusively in fresh water. The largest seal is the Southern elephant seal (bigger than even the walrus) and the smallest is the ringed seal. True seals lack ear flaps and propel themselves through the water with their hind flippers. When on land they shimmy like a caterpillar.

Fur Seals

There are nine species of fur seals, which are close relatives of sea lions. They have visible ear flaps, strong front flippers, and the ability to walk on all four flippers when on land. Males are larger than females—in some species they can be up to four times larger. While other pinnipeds rely on their blubber to keep warm, fur seals rely on a thick coat of fur. This coat includes both a waterproof undercoat and a top “guard” hair coat.

Sea Lions

There are five species of sea lion—the California sea lion, Steller sea lion, Southern sea lion, Australian sea lion, and Hooker’s sea lion. Sea lions (and fur seals) are distinguished from true seals by their comparably large front flippers, visible ear flaps, and ability to curl their back flippers under their body to walk on all fours. Sea lions are vocal, expressing themselves in loud barks. They are also social creatures, sometimes congregating in social groups of up to 1,500 individuals. Unlike fur seals, sea lions do not have a significant fur coat and instead rely on blubber to stay warm.

Walruses

The walrus is the only remaining species of its genus; however, genetic studies show that there are two distinct subspecies of walrus, the Atlantic walrus and the Pacific walrus. Unlike all other pinnipeds, walruses have two canine tusks that protrude from their upper jaw. These tusks help them forage for clams and mussels in the muddy seafloor and are used to pull themselves up onto the ice when they surface. Like sea lions, walruses curl their back flippers under their body to walk on all fours.

Evolution

The earliest ancestors of seals and sea lions were mammals that transitioned from life on land to life at sea. Around 36 million years ago, at the end of the Oligocene, the ocean began to cool, which caused major changes to ocean circulation. This led to an increase in nutrients throughout the ocean and enabled ocean life to thrive. The pinniped’s ancestors were likely drawn to the ocean due to its abundance of food and over time they evolved to life in the water.

Pinnipeds evolved from the ancestors of the musteloids which include everything from the red panda to skunks, badgers weasels, and raccoons. One potential ancestor was Puijila, an otter-like creature with a long tail and webbed feet that likely lived by freshwater lakes about 24 million years ago. As both a land and water dweller, it used its strong leg muscles to paddle through the water. Since it likely walked on all four limbs, scientists consider Puijila to be a transition species that illustrates the evolution from land animal to marine animal.

Fully flippered pinnipeds did not emerge until roughly 17 million years ago off the coast of modern-day Washington and Oregon. Enaliarctos, a genus that includes five known species, is considered the group that all present-day pinnipeds descended from. All four of their limbs were flippered, and they likely propelled themselves through the water using both the front and back flippers.

Ecology and Behavior

Reproduction

Mating season means different things for different pinniped species. For some, it means hauling out of the sea in massive rookeries on shore, while for others it can mean finding a sturdy ice floe.

For the majority of pinnipeds, including all fur seals and sea lions, the mating season begins in spring when males come to shore to establish territories. Only a select few males get the opportunity to mate, resulting in fierce competition over territory. In many species, males have evolved to be much larger than females, a characteristic called sexual dimorphism. Drawing on large reserves of blubber, males dutifully remain on land and guard their territory. Barking and trumpeting can alert an approaching male to steer clear of a claimed area, but if a male enters another’s territory fighting ensues. Elephant seals can be especially brutal and fights will often draw blood. Such territoriality means bulls stay on land for up to three months to guard their territory and will even forgo feeding.

About a month after males come ashore the females begin to arrive. They congregate in the male territories in groups called harems. Many are pregnant from the last year’s mating season and within a few days they give birth. The next few days are dedicated to bonding—mom and pup learn to recognize one another’s unique smell and voice, a necessity for the coming months when mom will leave to find food in the ocean. Upon her return they will need to reunite within the chaos of the rookery, and both smell and vocalizations help them do so.

Once bonding has occurred, the female prepares to mate again. She enters estrus, or heat, a reproductive state that advertises to the males that she is fertile. Females will mate with at least one of the males. Once the egg is fertilized it stops growing and remains in a dormant state for three months. Part of the reason for this delay is that pinnipeds must give birth on land but fetuses take nine months to develop. The delay allows for birthing to align with the annual trip ashore.

After females mate the next few months are dedicated to fattening the pups. In some species, mom will spend several days at sea foraging for food and then returning to feed her pup with milk. In other species, mom lives off her fat reserves and stays with her pup continuously until it is weaned. After a few months, the two return to the ocean and the pup learns how to forage for itself.

On the ice things are different. For species that mate on free floating ice floes, females are usually spread out over large distances, so males only have the opportunity to mate with one female per season. Ice is also unstable, and will break up differently from year to year, making the breeding season relatively short. Ringed seal pups are nursed for as little as three to six weeks before they become independent of their mothers. Unlike any other seals, ringed seals build snow lairs on the ice that help protect the pups from weather and predators.

In species that breed on pack ice, or stable ice attached to land, females may congregate in small colonies around a breathing hole. In this case, males sometimes will breed with multiple females in the same colony. When harp seals are born the mother spends about 12 days nursing the pup before she leaves in search of the males. The pup, a snowy white color, must quickly gain weight and learn how to swim or else drown when the ice pack breaks up. Once their mothers have left the pups rely on the sea ice to rest. In recent years, like in 2010, entire cohorts of seal pups have died when the ice broke up earlier than normal.

Pups in all species need to gain weight quickly. Like other marine mammals, pinniped moms make milk with a very high amount of fat, which helps their pups to quickly develop a thick layer of protective blubber. In some species, pups can gain several pounds every day.

Movements

During breeding season pinnipeds stick close to or on the shore, and this has a significant influence on their migration patterns. In general, smaller pinnipeds will leave the shore during breeding to feed nearby, while larger pinnipeds will stick to shore throughout the entire breeding season and then make significant migrations to far away feeding grounds where they build up fat reserves. Pinnipeds that live in the ice often migrate north in the summer and south in the winter to follow the ice.

One of the most prolific pinniped swimmers is the northern elephant seal. Although they breed along the coast of California and Mexico, northern elephant seals migrate nearly as far west as Japan, and as far north as Alaska to forage for food. During their time at sea they spend between 80 and 95 percent of their time underwater, only popping up to the surface for a quick breath before diving back down. Efficient use of flipper strokes, lots of blubber to make them buoyant, and a surprisingly low metabolic rate allow northern elephant seals to be highly efficient swimmers. The longest recorded trip was over 13,000 miles long. Overall, female northern elephant seals are the ones that make the longest migrations and they spend about 66 percent of the year in the high seas.

In the Food Web

Pinniped diets consist of mostly krill, fish, and squid. Many species will switch prey depending upon the season or what type of food is most abundant. Some species like elephant seals and harbor seals hunt alone, while sea lions and fur seals often hunt in groups. Walruses, however, do not hunt prey in the water column but rather forage with their snouts in the mud for bivalves, like clams. When a walrus finds a clam, it sucks it into its mouth and then uses its tongue to pull the shells apart through suction. It’s a highly efficient means of eating clams—walruses consume about six clams per minute using this suction method.

While many pinnipeds will feed on several types of prey, some are specialized feeders, preferring one type of prey. The crabeater seal does not eat crabs like its name suggests but rather feeds on krill. This seal evolved specialized teeth with grooves that act like a sieve and filter the krill from the surrounding water. Off the coast of Antarctica, the leopard seal is a formidable predator. It is a known penguin hunter, and will snag the birds with its canines and thrash them against the water’s surface. Leopard seals have been known to occasionally hunt other seals too.

Both on land and in the sea, pinnipeds are in danger of becoming meals themselves. Sharks, orcas, and polar bears prey upon seals as a main source of food. One polar bear must eat up to 19 baby ring seals every 10 to 12 days to maintain its body weight. In the Pacific Northwest, some orcas feed exclusively on fish while others predominantly eat seals and sea lions. In Antarctica, pods of killer whales will stalk seals resting on ice floes. Foxes, coyotes, and large birds like ravens will also prey upon young seals, and sea otters in the Pacific have been known to attack young harbor seals.

Human Impacts and Solutions

Extinction

When Christopher Columbus sailed to the new world he came upon a group of seals on an island in the Caribbean. Columbus’ son wrote, “As they were leaving that island they killed eight sea wolves which were sleeping in the sand…the animals are unaccustomed to men.” The “sea wolves” were actually a species of seals known as the Caribbean monk seal, a species that is now extinct. European colonizers hunted these seals in earnest between the 1700s and the 1900s, with the seal’s blubber fetching a significant price in a world that ran on animal oil. An account from 1707 tells of how a hundred seals were killed in one night. The last known Caribbean monk seal was seen in 1952, and the species was officially declared extinct in 2008.

Today, the Hawaiian monk seal and Mediterranean monk seal are two of the most endangered seal species in the world. Around the Hawaiian Islands there are about 1,400 Hawaiian monk seals, about one third of its historic population. Extensive conservation efforts have been put in place to save this species, but food limitation, entanglement, new shark predators, and habitat loss all contribute to their inability to rebound. There are fewer than 800 Mediterranean monk seals, which have been hunted since the Stone Age along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. The greatest threat to the Mediterranean monk seal is human interaction. These seals rely on coastal caves in undisturbed areas, which are becoming increasingly rare in the continuously developing Mediterranean coastline. Mediterranean monk seals also become entangled in fishing gear, where they are unintentionally killed. Recent efforts to protect their caves and work with local fishermen show signs of helping this species to slowly recover.

Climate

Floating sea ice is a critical resting and breeding place for pinnipeds living in the poles. As climate change warms the planet and melts sea ice, polar pinnipeds are losing this needed space in the middle of the sea. Walruses are especially vulnerable because they cannot stay in deep water for extended periods of time like seals. Recently, herds of walruses have come ashore in Point Lay, Alaska, sometimes in numbers as high as 40,000 individuals. When gathered in such high densities there is the risk of stampeding—a polar bear, hunter, or even an airplane can spook the herd. Such an event often kills many of the younger walruses who are caught in the frenzy.

Ringed seals are also struggling in a world with less sea ice. Ringed seals rest and raise their pups on ice floes. Additionally, they rely on snow to dig out ice caves on the floes. These caves serve as protection against predators like polar bears and orcas as well as against severe weather. A decrease in snow cover correlates to a decrease in seal pup survival. One study predicts that by the year 2100 the climate will cause at least a 50 percent reduction in the ring seal population.

Climate may also change the types of food available to pinnipeds. Galapagos sea lions historically ate sardines as the main source of their diet. But as climate change has gradually warmed the region, these fish have become scarce. During El Nino years when the water is particularly warm, up to 100 percent of newborn pups and up to 50 percent of yearlings die due to starvation. As a result, over the last 30 years the Galapagos sea lion population has shrunk from 40,000 individuals to fewer than 15,000. Without an abundant source of sardines, sea lions have had to get creative when it comes to finding food. In recent years they have been observed working in teams to corral and catch yellowfin tuna. Tuna swim about twice as fast as sea lions and so the sea lions have learned to use the maze-like shoreline to trap the fish. The entire endeavor takes time and energy, but when successfully executed, a 50-pound meal is quite the reward.

Sea level rise could also greatly endanger pinnipeds, especially those in warmer waters. Hawaiian monk seals, for example, rely heavily on the atolls of the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, some of which only rise a few feet above current sea level and may become completely submerged if sea levels continue to rise. In the Mediterranean, monk seals inhabit coastal caves that may become increasingly flooded with rising sea levels.

Captivity

Today seals and sea lions delight visitors of zoos and aquariums with their endearing personalities. For the most part, seals and sea lions steal the show. But the first pinnipeds to be caught and taken from the Arctic for entertainment purposes were walruses. These initial attempts at captivity, however, were complete failures. In 1608, two young walruses were captured and taken aboard the “God-speed.” En route to London the female died, and the male died soon after arrival. The next walrus calf to arrive in London was in 1853, and a third arrived in 1867. They, too, died shortly after arrival, likely due to the diet they were fed by their captors. Accounts of baby walruses kept on ships describe how they were fed salt fish, salt beef, vegetable purees or, in one case, an oatmeal and pea soup—milk was not available. The death of one walrus prompted an autopsy, revealing that it had no fat.

Walruses became a sought-after animal for zoos in the early 1900s, but it wasn’t until after WWI that zoos were able to care for them effectively. Most walruses only lived a few years before they succumbed to pneumonia or an ailment tied to malnourishment. In 1949, a walrus at the Copenhagen Zoo named Gine became the longest living walrus in captivity. She lived for 11 years and 10 months. It wasn’t until the 1960s that zoos had the knowledge and ability to supply proper nourishment to walruses and allow them to grow properly. Even today, there are few walruses held in captivity.

Seal and sea lions, however, are staples in aquariums and zoos. Thirty-two species of sea lion and seals have been held in captivity with the first captive seals dating back to the Roman Empire. During the height of the Empire, Mediterranean monk seals were included in the elaborate parades and celebratory animal slaughtering in the Colosseum. They were also displayed around the Empire in travelling circuses or zoological gardens, where they were trained for public entertainment. Though the slaughter of seals for entertainment likely ended with the fall of the Roman Empire, the display of seals in travelling circuses around Europe continued through to the 1800s with handbills advertising them as “talking fish,” “merman,” or “sea monsters.” Like the walruses, these captives were usually young and didn’t live for more than a couple of months. By the turn of the 20th century Mediterranean monk seals were rare in the wild, a fact that made them even more desirable for zoos.

In the United States, seals were stars at the country’s first aquarium—the Boston Aquarial Gardens. Ned and Fanny were likely harbor seals and, acquired in 1856, were soon trained to perform complicated tricks like playing a hand organ. In New York, the endangered Caribbean monk seal became the most popular attraction at the New York Aquarium, which housed a number of seals from this species throughout the early 1900s. These seals, with names like Nellie and Tom, were celebrities in the City, with their deaths even reported in the New York newspapers and their remains donated to the collection of the American Museum of Natural History.

Today, harbor seals and California sea lions are the most common pinnipeds in zoos and aquariums.

Cultural Connections

Seals and the Kayak

A common recreational boat in modern day, kayaks have been used by the Inuit for thousands of years, and seal and walrus skins were a major part in their invention. Supple, sturdy, and waterproof, sealskin is an excellent material for the creation of boats. Due to scant resources in the Arctic, they were built with light frames made out of driftwood or animal bones. The skins were stretched over the frame and oiled periodically with fat obtained from either seals, walruses, or whales, to maintain the waterproof capability. Kayaks were usually built for a solo hunter, but the Inuit also built larger boats called umiaqs (also spelled umiak) that could fit over ten people. Reliance on animals for survival required the Inuit to follow animals as they migrated, and Umiaqs helped move personal belongings and provided transportation for those unable to travel distances on their own, like children.

Famous Pinnipeds

The most famous pinniped in New England was a seal named Andre. In 1961, Harry Goodridge, the harbormaster of Rockport Harbor, Maine, adopted an abandoned harbor seal found in the Penobscot Bay, Maine. Named Andre, the seal chose to stay with Goodridge and for the rest of his life he spent the warm seasons in Penobscot Bay. As a pup, Andre lived in the Goodridge house and would even watch television with the family. Later, he and Goodridge would perform daily shows on the docks for tourists, a tradition that lasted until Andre’s death at 25 years old in 1986. Today, a statue of Andre sits on the shore of Rockport Harbor. During his life Andre attracted significant news coverage, and later Paramount filmed a movie inspired by Andre’s story. To the dismay of many a sea lion and not a seal was used to portray Andre in the film. Seals, sea lions, and walruses also play many side roles in a variety of cartoons and children’s films, including “Finding Dory,” the “Madagascar” films, and “Ice Age 4.”