Slow Down for Right Whales

Right whales in the North Atlantic are real city slickers. Rather than spend their time in the ocean’s wide-open range, they swim in warm coastal waters (sometimes near Boston, Charleston, Philadelphia, New York and other cities along the eastern United States) to feed on copepods and other plankton that thrive there. In the winter, right whale moms give birth to calves near southern states like Georgia and Florida. Then they swim north to New England and the southern coast of Canada to feed during the spring and summer months.

That the whales prefer the same coastal waters that people do has plagued them for centuries. In the 1600s, many thousands of right whales were killed by whalers; their tendency to feed at the ocean’s surface within 50 miles of shore made them easy targets. They were hunted so persistently that, by some estimates, less than 100 right whales survived along the U.S. East Coast by the early 1900s.

Today, hunting right whales is illegal; an international treaty signed in 1935 protects them. But they still face a suite of threats as they swim offshore. There, large ships navigating to ports strike the whales, often killing them. They find themselves entangled in ropes from fishing gear, which leave permanent scars and increase risk of infection. Toxic algae blooms, made worse by urban pollution, can poison calves or obscure the whales’ plankton food.

“It’s the cumulative effects of living in the east coast of North America, which is pretty industrialized,” says Scott Kraus, the vice president of research at the New England Aquarium and co-author of The Urban Whale. When Kraus was a young right whale scientist in 1980, little was known about the Northern right whale population — except that it was small, at less than 300 animals. Since then, he’s led initiatives to identify the threats that ail them and protect them.

The Whale Catalogue

To protect right whales, you first need to know a few things about them — how they interact with their environment, each other, and people. But unfortunately, “you can’t ask them questions about how they’re doing,” says Kraus. As an alternative, in the early 1980s he launched an effort that has proved crucial to right whale conservation and research: The North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog.

The North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog takes advantage of right whales’ distinctive white patterns (called callosities) to identify and name each animal. Using photographs, Kraus and other researchers piece together biographies for each whale — who’s spending time with whom, where they’re spending time, and which calves belong to which mothers. In recent years, scientists have added genetic information and other health data, too.

All this tracking has taught researchers about right whale reproduction, which is important if you want to be sure the population is healthy and growing. They’ve learned that most right whale moms give birth to their first calf when they’re 10 years old, and that healthy moms can give birth every three years. That is a slow reproductive rate — and means that every whale counts, especially mothers.

The catalog also told them which whales died and how. Kraus found himself repeatedly recording the same cause of death: collisions with large ships. Between 1970 and 1999, 45 right whales were found dead — and ships killed one-third of them. “They live in the coastal waters, so they’re all right up against these port entrances,” says Kraus. Several of those whales were new moms; with their deaths, the right whale population lost not only those individuals, but all the calves they would have birthed throughout their entire lives. “Gradually it became obvious that this was an existential threat to right whale recovery and therefore we needed to do something about it,” he says.

Slow for Whales

Amy Knowlton, a right whale researcher at the New England Aquarium who’s worked with Kraus for 25 years, led the charge by organizing research to figure out how to reduce collisions between right whales and ships. The problem, she learned, was twofold. First, at some ports, ships cross directly through areas where right whales tend to gather. Second, the ships move so quickly that right whales don’t have time to get out of the way.

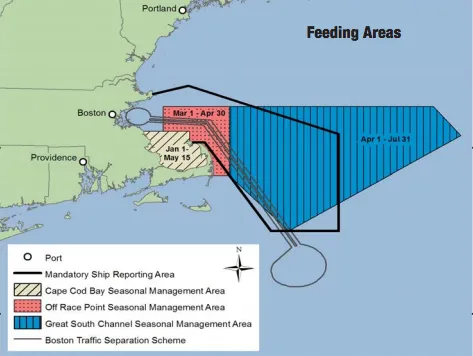

At the same time, Knowlton talked extensively with the National Marine Fisheries Service, the International Maritime Organization and the shipping industry. After a decade of negotiation, they agreed to create a speed limit of 10 knots (or 11.5 miles per hour) for larger ships (longer than 65 feet) in the winter and spring, when right whales migrate offshore. The speed limit takes effect at different times in different places, depending on the whales’ typical location. So during calving season, the speed limit is enforced up to 20 nautical miles (23 miles) offshore of Georgia and Florida. When the whales reach Cape Cod to feed, the speed limit is enforced there.

A good comparison is speed limits near schools, says Kraus. In the months when school is in session and children are playing nearby, cars have to drive slowly near schools to prevent accidents. Similarly, ships have to drive slowly near right whales. “If you want to save the kids, you drive slowly; if you want to save the whales you drive slowly,” he says. “It’s pretty intuitive.”

Some workers in the shipping industry were not thrilled about the new rules, which went into effect in 2008. They worried about wasting fuel, upsetting shipping schedules, and losing business to ports that don’t have right whales or speed limits. They resisted the rules at first — but they’ve adjusted well since then, says Kraus. “It turns out that slowing the ships down increases their efficiency, they’re saving fuel, plus there’s fewer emissions,” he says. “So what’s not to like?”

It hasn’t been long, but so far it seems as though the rule has helped. Between 1990 and 2008 (before the speed limit went into effect), ships killed 15 right whales in U.S. waters — and 13 of those whales were found within areas now protected by speed limits. Between 2008 and 2013, ships killed two right whales and neither were found within 50 miles of the protected areas.

“When [the National Marine Fisheries Service] put the slow ship rule into place in 2008, that actually did change the mortality rates from ship strikes,” says Kraus. In 2013, the right whale population hit a record high of nearly 500 animals — up from 295 whales in 1992.

Kraus hesitates to call the effort a complete success because the right whale population still isn’t recovering quickly enough. Immediately after the ship speed limits were made law, another threat to right whales took center stage: entanglement in fishing gear.

All Tangled Up

After ship strikes, the second biggest threat to right whales is entanglement in fishing rope, a problem that has gotten worse. As fisheries move offshore, lobster and crab traps grow heavier, and more and thicker rope is needed to haul them back to the surface, says Kraus. “What that has done is increased the severity of entanglements when they occur,” he says.

By studying patterns of scarring using the North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog, Kraus has found that 82 percent of right whales have been entangled at some point in their lives. When they’re entangled, they have trouble swimming and catching food. The ropes can cause injuries, and “the heavier the gear the worse the wound,” says Kraus. Even after they’re freed, the whales’ immune systems have to fight infection and recover — a process that can take a year or more.

The scary part, says Kraus, is that these entanglements seem to be hurting whale moms. Recently, they’ve been birthing calves every 5 years instead of every 3 years, and it looks like poor health from entanglements is to blame.

Kraus is currently researching new kinds of fishing gear to better protect right whales. Special ropes could break apart when a whale becomes entangled; another option is to use bright red ropes that whales see more easily in the water.

There are enough possibilities and concerned fishermen that he’s confident that they’ll find a solution. But he knows it will take time and effort, just like the speed limit rule did. “I do feel optimistic about it. But it’s a campaign,” Kraus says. “You just have to be bloody persistent.”

This story was made possible by a grant from the Smithsonian Women's Committee. http://swc.si.edu/about-grants