Tohunga Tohorā’s Intuition Reveals New Whale Species

When Ramari Stewart laid eyes on the beaked whale that had washed ashore on the west coast of Te Waipounamu (South Island), Aotearoa New Zealand, she knew it was special. A renowned Tohunga Tohorā (whale expert) who was raised by her elders in the traditional Māori knowledge of the moana (sea), Stewart recognized that the whale was different than any other known.

“When Nihongore turned up I knew that she was something different, I knew it was special because I hadn’t seen it before,” said Stewart.

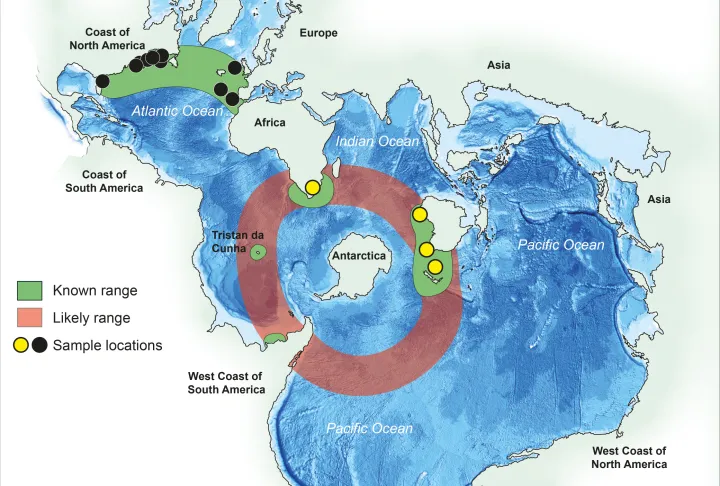

New Zealand researchers initially suspected the whale was a True’s beaked whale, a similar whale that inhabits the Northern Hemisphere and temperate waters of the Southern Hemisphere around Australia, South Africa and South America. But this whale had not been seen in New Zealand waters before. Emma Carroll, a collaborator of Stewart’s at the University of Auckland, thought the presence of a True’s beaked whale in New Zealand warranted more study. As she compared the genetics of the New Zealand whales to other True’s beaked whales she was studying in the Azores she noticed they were not the same.

“Just one genetic marker gave a tantalizing hint that the True's from the North Atlantic and Southern Hemisphere were different. But we needed more samples and more information to investigate further,” said Carroll. Carroll turned to other whale researchers worldwide, including Michael McGowen at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, and together they amassed enough genetic information from a number of whale specimens to show what Ramari suspected all along—New Zealand’s beaked whales were not True’s after all.

Beaked whales in general are shy, steering clear of boats and the eyes of people. They are also prolific divers, spending much of their time far out at sea and deep underwater. This behavior has made it difficult to study beaked whales, and part of the reason why it has taken this long to determine that this was indeed a new species. Much of what we know comes from whales that wash ashore.

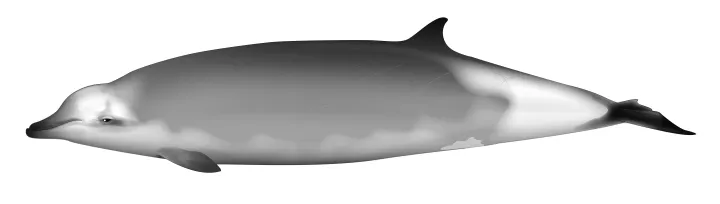

Even when whales are found, the differences from one beaked whale species to the other are so slight that even whale specialists have difficulty identifying them. In 1959, a beaked whale washed ashore 170 miles east of Cape Agulhas, the most southern tip of South Africa, and after examination by local scientists and specialists at the British Museum of Natural History it was determined to be similar to True’s beaked whale (incidentally, a whale that was discovered in 1913 by Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution Frederick W. True). However, scientists noted at the time “that the lower jaw of the South African specimen appears deeper and more massive” than a True’s whale skeleton from the British Museum.

We now know why it seemed so different. The True’s beaked whales of the Southern Hemisphere are actually a different species.

“It’s pretty cut and dry. Based on genetic data and morphological data, we found that they are two different species,” said McGowen.

As a nod to the integral role of Indigenous knowledge in the discovery, the new species, Mesoplodon eueu, is named in honor of the indigenous Khoisan peoples who inhabited the South African territory. The name eueu was given, meaning “big fish” in the Khwedam language of the region, a representative of languages found in coastal regions where the whales strand that is now mostly extinct. The common name will be Ramari’s beaked whale, in honor of Ramari Stewart. It is the first time a whale is named after an Indigenous woman.

For Stewart, it was clear from that first look that the whale was special. At the age of 10 she had been named a whale rider, a designation by the Māori people for a person with a special bond with whales. She would go on to spend extensive time studying whales, even building boats in order to become personally acquainted with a pod of common dolphins. A nurse by profession, she learned of the annual right whale gathering off the coast of Campbell Island and took up a job as a cook, medic, and technician at the meteorological station there in order to get close to them.

Stewart’s knowledge of whales is extensive, though perhaps not traditional in the sense of Western science. Much of her knowledge comes from her elders, relayed to her through spoken word and experiences by the sea. She has also participated in countless whale strandings—conducting government-sanctioned research and performing the customary traditions associated with the recovery of resources from whales. Whale strandings are common along the shores of New Zealand and the Māori people have viewed them as “he taonga Tangaroa,” or “gifts from Tangaroa,” and a resource to be used and treasured. Stewart often straddles between the world of her people and the world of Western science, a fact that has hindered the acceptance of her research in the past. More recently, however, there has been a recognition that cultural knowledge and scientific practices complement one another.

“It’s wonderful that Western science is starting to recognise that Mātauranga Māori is as equally great as Western science and the two can work together. Rather than just bridging a relationship and taking knowledge from Indigenous practitioners, it is better that we both sit at the table,” said Stewart.

The combined knowledge from Indigenous culture and Western science enabled the discovery of Ramari’s beaked whale. Stewart recognized that the whale was different, and enabled the collection of the remains from the beach where it washed ashore. An initial genetic study by Carroll hinted that the whale was likely not what it first appeared, and at the Smithsonian, McGowen used the True’s beaked whale holotype (the original specimen used to compare all other specimens of a species) to confirm that the two were in fact distinct.

Carroll sums up the collaborative effort best, “It has taken a village as they say, as these whales are so rare we needed to collaborate with many people around the world to analyze enough samples to see these patterns.”