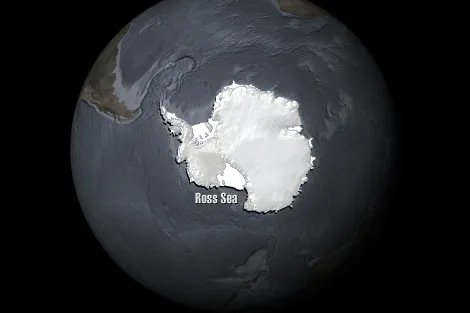

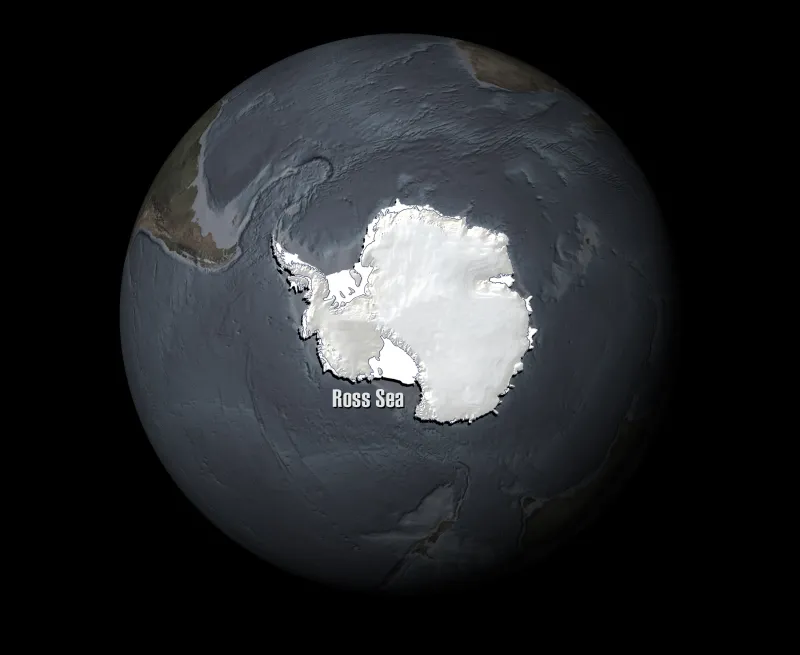

The Ross Sea, a 1.9 million square mile (3.6 million square km) stretch of ocean off the coast of Antarctica, has been nicknamed “The Last Ocean.” And it’s not just a ploy to get your attention. In 2008, researchers mapped out human impacts on the ocean globally and this small area of the Southern Ocean proved to be the most pristine piece of the ocean left on Earth.

A Trip South to Antarctica’s Ross Sea

The Ross Sea, a 1.9 million square mile (3.6 million square km) stretch of ocean off the coast of Antarctica, has been nicknamed “The Last Ocean.” And it’s not just a ploy to get your attention. In 2008, researchers mapped out human impacts on the ocean globally and this small area of the Southern Ocean proved to be the most pristine piece of the ocean left on Earth.

John Weller, a photographer and conservationist, has captured the remote beauty of this ecosystem, highlighting the amazing wildlife, including whales, seals, penguins, fish and krill, and the ice they live alongside. Despite the great distance from civilization, the Ross Sea faces threats from commercial fishing, whaling and extreme climate change.

Map of the Ross Sea

Credit: Courtesy of John Weller

Antarctic Pack Ice

Credit: © John WellerEvery year as the sun disappears for the winter, the surface waters around Antarctica freeze into a slab of ice 10-feet thick, which effectively doubles the size of the continent. In the summer, the slab of ice breaks up into pack ice, which eventually drifts out to sea and melts, only to be replaced the next year. Sea ice is a critical habitat for nearly all the denizens of Antarctica, and is changing quickly in response to climate.

Ross Sea Ice Shelf

Credit: © John WellerAntarctica is almost entirely covered by ice sheets up to two miles (3 km) thick, which contain roughly 70% of the world’s freshwater. The great ice sheets spill out to sea as floating ice-shelves and ice-tongues, which routinely calve massive icebergs into the waters around Antarctica. The Ross Sea ice shelf is one the largest ice shelves in the world. It is the size of France, and though the 200-foot-tall cliffs of ice extend 500 miles, that is just, as they say, the tip of the iceberg. Most of the ice lies hidden below the cold, dark salt water.

Adélie Penguin Jumping Out of the Water

Credit: © John Weller

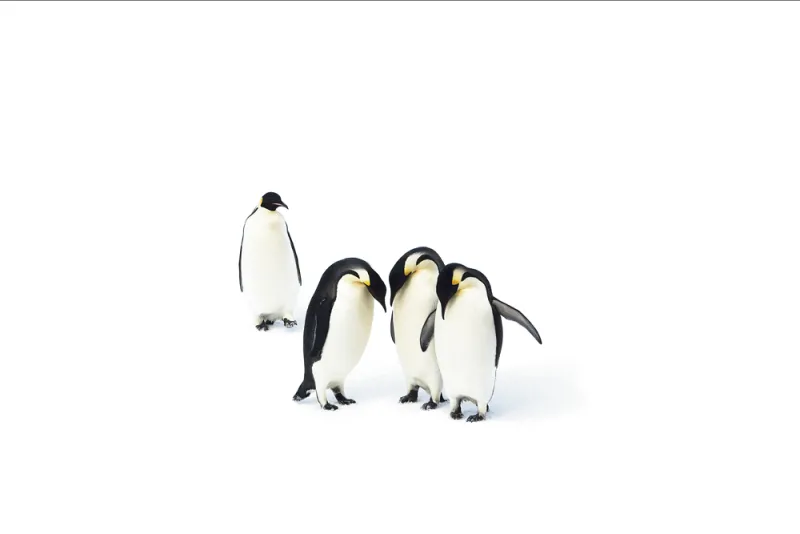

Emperor Penguins on the Ice

Credit: © John Weller

Antarctic Minke Whale

Credit: © John Weller

Orcas in the Antarctic

Credit: © John WellerThree distinct types of killer whale can be found in the Antarctic, each with a different habitat and diet preference. One type of orca preys almost exclusively on the Antarctic minke whale, another on seals, and the last eats fish. None have yet been described as separate species, but genetic testing will help scientists know if they should be.

Snow Petrel

Credit: © John Weller

Weddell Seal in Antarctic Water

Credit: © John Weller

Antarctic Ocean Floor

Credit: © John WellerThe dark seafloor beneath the ice is covered with sea stars, urchins and ribbon worms looking for their next meal, which can come from sponges, dead animals that float to the sea floor, or even other sea star species.

Anemone in Cold Antarctic Water

Credit: © John Weller

Cold-Water Sea Spider

Credit: © John Weller

Isopod in a Glass Home

Credit: © John Weller

Fish Adapt to Icy Water

Credit: © John WellerThis shadowy fish, Trematomus bernacchii, is well adapted to the ice-cold water of the Antarctic: its blood comes equipped with natural antifreeze. This is a necessary adaptation because the surrounding water averages minus 1.8 degrees Celsius, just above the freezing point of saltwater.

Floating Antarctic Comb Jelly

Credit: © John WellerBright colors seem to jump off of this comb jelly, or ctenophore. The rainbow effect appears when light emanates from comb jellies' namesake combs, which are rows of cilia that run up and down their bodies and propel their soft bodies through the water.

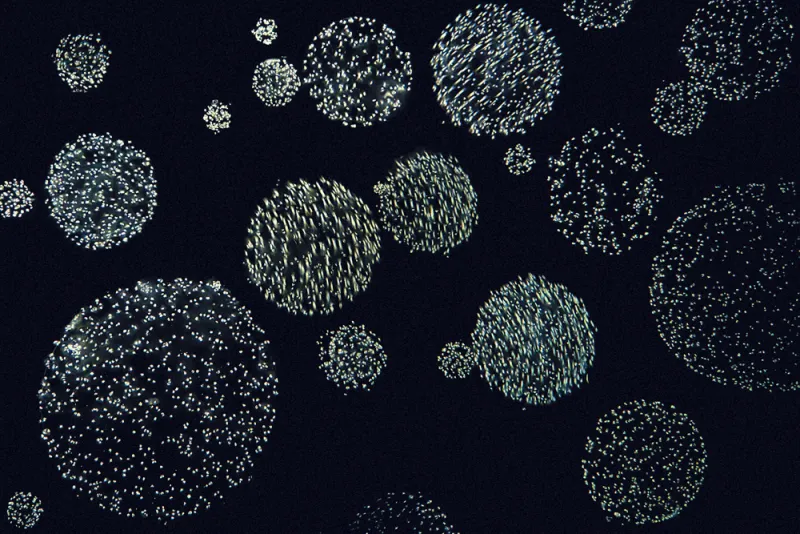

Phytoplankton Bloom in the Antarctic

Credit: © John WellerSeasons in the Ross Sea are marked by ice freezing and melting, and these processes mix the seawater and redistribute salt and nutrients. The influx of nutrients cause phytoplankton to bloom, forming patches of algae in the Ross Sea that are so large that they can be seen by satellite. Here you see polar algae up close, under the lens of a microscope.

Protecting a Pristine Ocean

Credit: © John WellerWhile the Ross Sea is perhaps the most pristine place left in the world’s ocean, the human footprint is changing this last place quickly. Even as the effects of climate change are redefining the very fabric of the ecosystem, we have started to exploit the natural resources of the Ross Sea. And though the Ross Sea is in much better shape than the rest of the world’s ocean, protecting this last wilderness could help set the stage for a new age of protections for other critical marine ecosystems around the globe.