The Marine Sanctuary: A Safe Harbor for Ocean Life

When most people think of iconic American landscapes, we think of places on land. Yellowstone, the Great Smoky Mountains, the Grand Canyon—these national parks are household names.

But many Americans don't realize that we also have a network of protected areas in the waters off our coasts. From the chilly waves on Washington's Olympic Coast to the warm shallows ringing the Florida Keys, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) maintains 13 National Marine Sanctuaries and co-manages one Marine National Monument. These, together with marine protected areas designated by local governments, are a crucial tool in managing ocean resources.

By comparison to protected areas on land, our system of marine sanctuaries is new and small. Yellowstone, our first national park, was established in 1872. But the first national marine sanctuary—protecting the wreck of the Civil War ironclad the U.S.S. Monitor—wasn't designated until 1975. While 18 percent of U.S. lands are federally protected (as national parks, forests, or wildlife refuges), less than four percent of U.S. waters are included in the sanctuary system.

Like national parks, sanctuaries are tools with many functions, and they showcase everything from historic shipwrecks to the migratory paths of whales and birds. Some help conserve and restore damaged habitats or imperiled species. Scientists use some as research tools, and others offer visitors recreational opportunities and educational programs. Most sanctuaries have a combination of these elements.

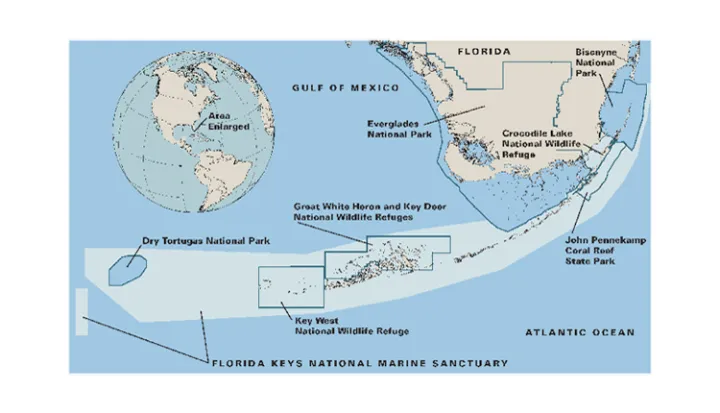

In Florida, decades of pollution, coastal development, recreation, and over harvesting damaged the reefs, prompting Congress to add the Florida Keys coral reef ecosystem to the National Marine Sanctuary System in 1990. Since then, sanctuary scientists have been working on conservation projects like restoring seagrass beds and corals damaged by boat groundings. In specially protected areas of the sanctuary where removing marine organisms is not allowed, scientists are seeing increases in important fish species whose populations had been declining.

Designated in 2006, the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands contains some of the ocean's last-remaining, relatively undisturbed coal reef ecosystems. At nearly 140,000 square miles, it is the largest marine protected area in the U.S. Its designation included a plan to phase out commercial fishing, bans on dumping and drilling, and limits on visitors and boat traffic. The monument is home to a rainbow of wildlife including many endemic (only found in that location) species, highly endangered Hawaiian monk seals, and threatened Hawaiian green sea turtles. It also offers scientists a rare opportunity to study naturally functioning coral reefs.