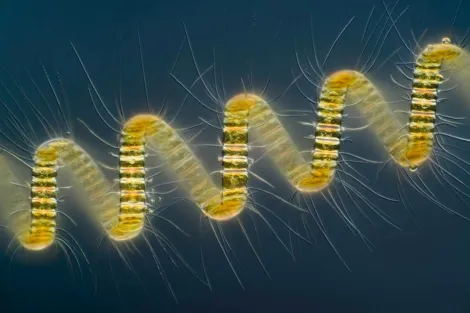

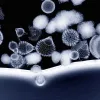

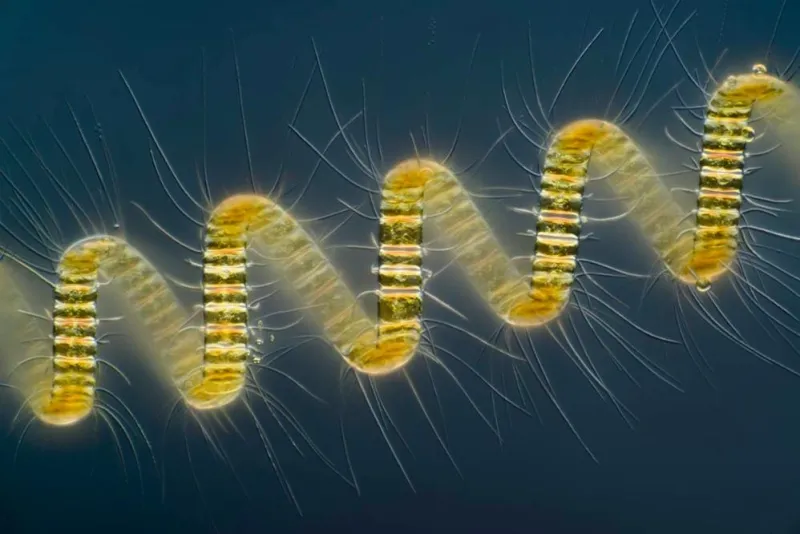

This beautiful marine diatom Chaetoceros debilis was caught in the North Sea. Not only are diatoms one of the most important oxygen producers on earth, they are also a vital link in the food chain. This spiraled diatom has cell walls made of silica, each containing a cell that glitters like gold and spiky spines that help it stay afloat. This image, taken at 250x zoom, took 1st place in the 2013 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

The Ocean Under the Microscope: Images from Nikon Small World

The ocean is so big that it can be easy to forget the microscopic beauty of the organisms that live within. Some of this beauty is documented by the Nikon Small World photomicrography competition, which since 1979 has awarded prizes to artists and scientists who take the most beautiful photos from under a microscope. In this slideshow, admire your favorite marine organisms (and some new ones) from a new perspective at up to 500x zoom.

A Diatom Helix

Credit: Wim van Egmond / Nikon Small World

A Snail's Rainbow Radula

Credit: David Maitland / Nikon Small WorldThis abstract image is a close-up of the tiny teeth that cover the radula of a common whelk (Buccinum undatum). A radula is a tongue-like ribbon that helps the snail scrape or cut its food before it swallows it. The image, taken at 200x zoom, was an honorable mention in the 2013 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

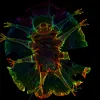

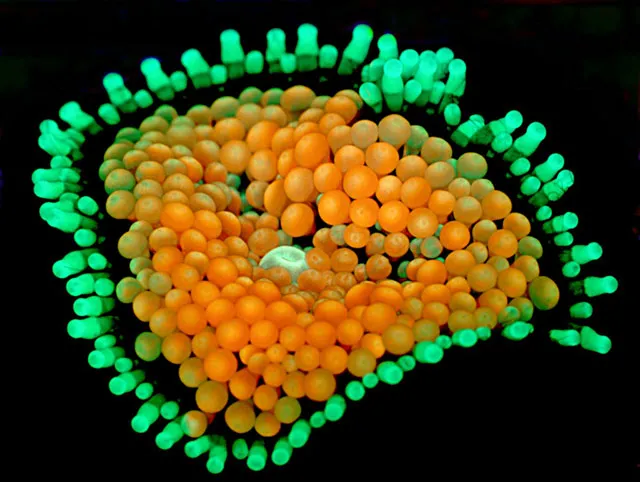

Soft Coral Close-Up

Credit: James H. Nicholson / Nikon Small WorldThese neon balloons weren't blown up for a party: they are the colorful tentacles of the corallimorpharian Ricordea florida. Unlike the shallow-water corals that build reefs, corallimorpharians don't have skeletons, but otherwise have very similar anatomy. This photo of a single live soft coral polyp, taken at 20x zoom, was named an Image of Distinction in Nikon Small World's 2013 photomicrography competition.

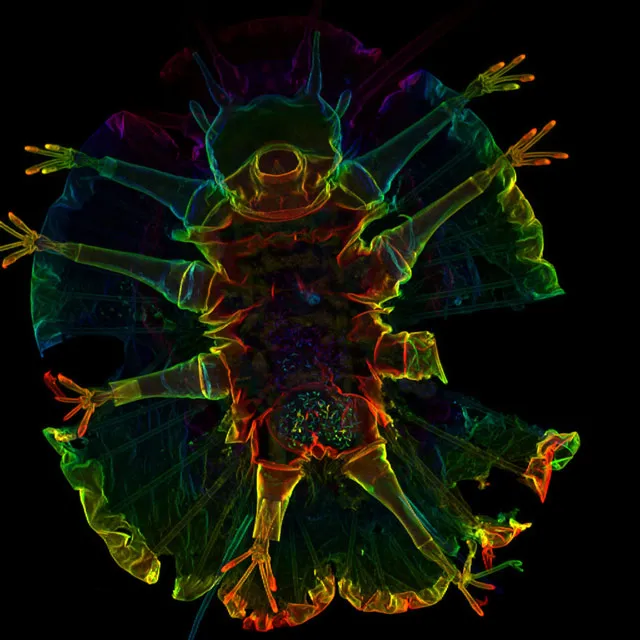

Psychedelic Tardigrade

Credit: Andreas Schmidt-Rhaesa, Corinna Schulze & Ricardo Neves / Nikon Small WorldTardigrades, which are usually less than 1 mm long, can be found in almost every habitat on Earth, and there are 150 known species found in the ocean. Tardigrades are most famous for being able to survive in extreme environments such as extremely hot (304 °F!) or extremely cold (-328 °F!) temperatures, X-ray radiation a thousand times the lethal dose, and even in the vacuum of outer space! This image of a marine tardigrade (or "water bear"), taken at 40x zoom, was named an Image of Distinction in the Nikon Small World 2013 photomicrography competition.

Spin Hagfish Slime into Silk

Credit: Steve Downing / Nikon Small WorldBelieve it or not, this unraveling thread is from hagfish slime. Hagfish are jawless, eel-like fish that ward off predators with the production of slime—stringy proteins that expand into a transparent, sticky substance. They can fill a 5-gallon button with the stuff in minutes, and it allows them to slip and slide away from attacking predators, which get a mouthful of slime instead of the fish. Each thread is remarkably strong and about 100-times thinner than a human hair, and some researchers are studying how to spin it into new fabrics. This image, taken at 63x zoom, won 20th place in the 1979 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

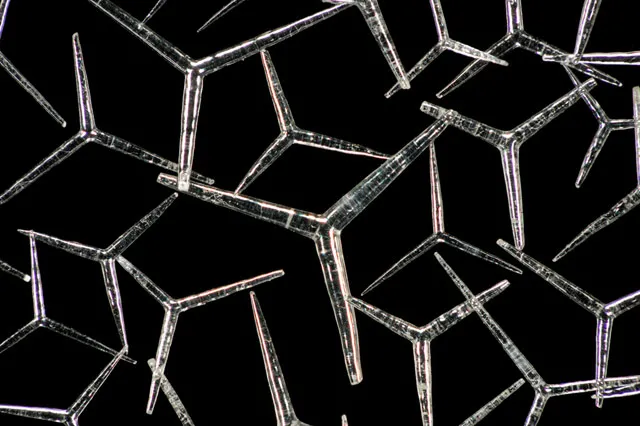

Sparkling Sponge Spicules

Credit: Solvin Zankl / Nikon Small WorldThese sparkling sponge spicules are microscopic needle-like structures that many sponges use as a structural skeleton and as a defense against predators. When such a sponge dies, it crumbles into tiny spicules, which become part of the sand in coral reefs. This image, taken at 10x zoom, was named an Image of Distinction in the 2013 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

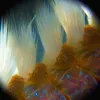

Sea Gooseberry Larva

Credit: Gerd A. Guenther / Nikon Small WorldThese beautiful wisps are the hair-like cilia of a sea gooseberry larva, a common type of comb jelly, which beat in rhythm to row the comb jelly through the water. When fully grown, sea gooseberries (Pleurobrachia sp.) are voracious predators, gobbling up fish eggs and larvae, small mollusks, copepods, and other sea gooseberries. The image, taken at 500x zoom, took 8th place in the 2012 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

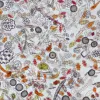

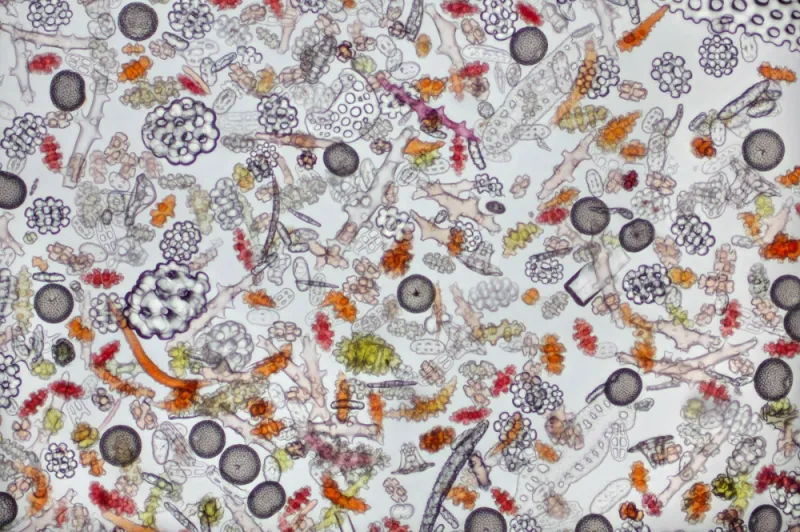

Coral Sand Under a Microscope

Credit: David Maitland / Nikon Small WorldCoral sand is aptly named: it's sand made up of tiny bits of coral and other ocean animals such as foraminifera, molluscs, and crustaceans. This image, taken at 100x zoom, took 18th place in the 2012 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

Deep-sea Copepod Gets a Close-up

Credit: Terue Kihara / Nikon Small WorldThis female deep-sea copepod (Pontostratiotes sp.) was collected in the southeastern Atlantic at a depth of 17,700 feet (5395 meters). How does it find food so deep in the sea? Tiny particles (known as marine snow) sink from the surface to the deep, feeding animals big and small. This photo, taken at 10x zoom and with artificial color, was an honorable mention in the 2012 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

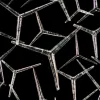

Glassy Radiolarian Beauty

Credit: Ralph Claus Grimm / Nikon Small WorldThe shells of radiolarians rank among some of the treasures of the ocean, with their intricate, gorgeous geometry. The shells are made of silica, which protects the single-celled animals as they drift as zooplankton in the ocean. This image, taken at 120x zoom, was an honorable mention in the 2012 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

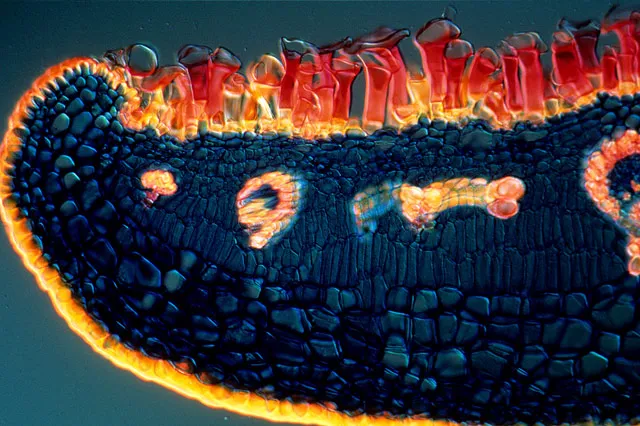

How Mangroves Deal with Saltwater

Credit: Daphne Zbaeren-Colbourn / Nikon Small WorldLooking at a white mangrove (Avicennia marina) leaf cross-section under the microscope, you can see a special adaptation it has for living in salt water. The red mushroom-like structures on the top of the photo run along the bottom of the leaf—they are tiny glands that excrete salt absorbed from seawater back into the environment. The glands can excrete so much salt that salt crystals form on the bottom of the leaf! This image, taken at 40x zoom, won 1st place in the 2000 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

Branching Red Algae

Credit: Arlene Wechezak / Nikon Small WorldUnder the microscope, you can peer inside the cells of this filamentous red algae. The thin, hair-like filaments are only one cell wide, seen here at 250x zoom. Red algae are red because of the pigment phycoerythrin, which along with green chlorophyll allows the algae to undergo photosynthesis and turn sunlight into energy. This image was named an Image of Distinction in the 2010 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

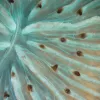

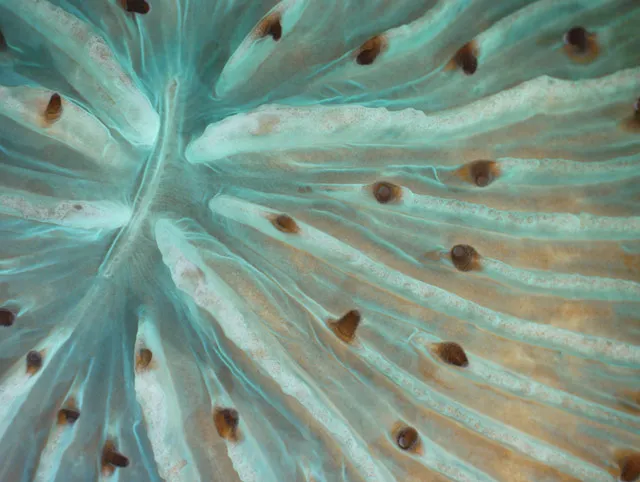

Closed-Mouth Coral

Credit: James H. Nicholson / Nikon Small WorldA live coral polyp with turquoise tissue and brown tentacles closes its mouth (the slit at the center of the radiating ribs) tight. The coral uses its tentacles to catch food, which it then funnels into its mouth. After eating, waste leaves through the same opening. This photo, taken at 6x zoom, was an image of distinction in the 2009 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition

Blue Button Tentacle

Credit: Christian Gautier / Nikon Small WorldThis tentacle belongs to a blue button (Porpita porpita), an animal that looks like a jellyfish but isn’t. While it has a central “float” with streaming tentacles like typical jellyfish, the blue button is a colony of many small hydroid animals. Some of the individual animals (zooids) make up the float, while others make up the tentacles. Despite differences, there is one major similarity: the tentacles have stinging nematocysts in those white tips, so do not touch! This image, taken at 50x zoom, was an Image of Distinction in the 2010 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

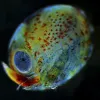

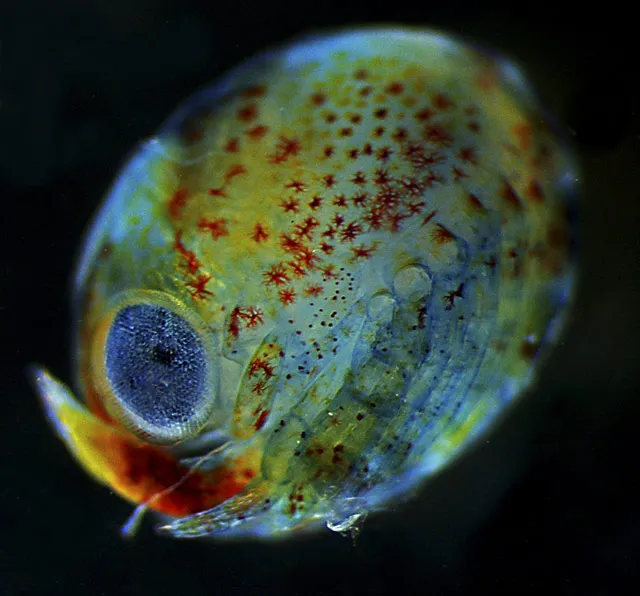

Lobster Egg

Credit: Tora Bardal / Nikon Small WorldEven when a lobster is still a developing egg, you can see some of its adult features: an eye and legs. After a female lays her eggs, she carries them around under her tail for 9 months to a year to protect them. When they are ready to hatch, she lifts her tails and the larvae, which look like tiny lobsters, drift into the waves. Over the next three to ten weeks, they will feed, grow and molt as plankton, before settling down on the seafloor. This image, taken at 3.2x zoom, took 14th place in the 2009 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

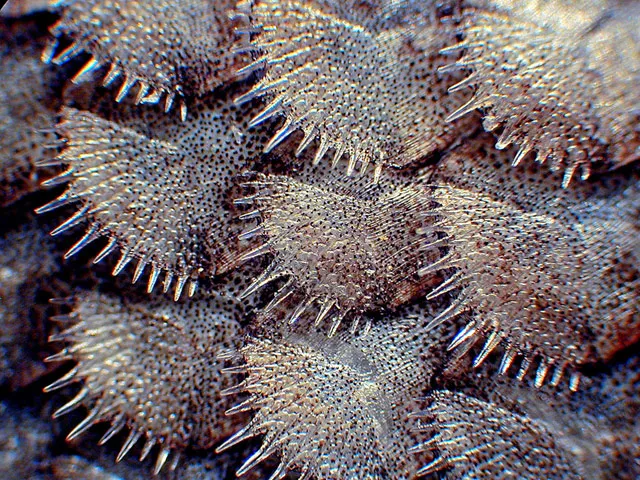

Close-Up of Dover Sole Skin

Credit: Lawrence Bowler / Nikon Small WorldThis close-up of the skin of dover sole (Solea solea) masks its true ability: to provide camouflage. Like other flatfish, dover sole spends most of its time burrowed in the seafloor with both eyes, located on one side of its body, looking up into the water. Its coloring allows it to blend in with the sandy bottom perfectly. This photo, taken at 20x zoom, was an Image of Distinction in the 2009 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

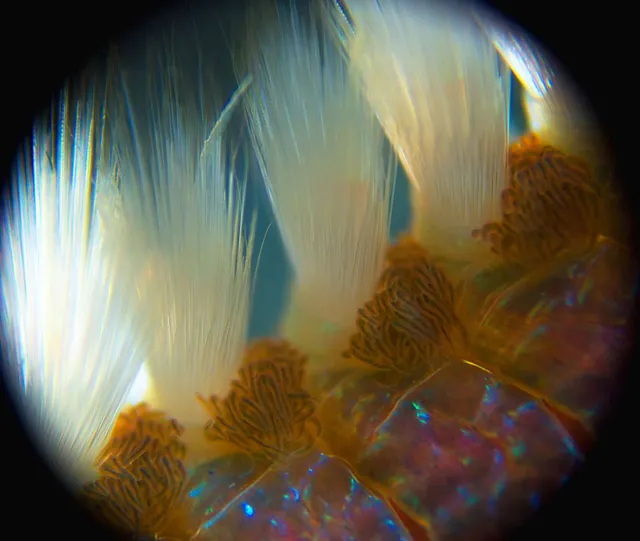

Fireworm Bristles

Credit: Jasper Nance / Nikon Small WorldNo, this isn't a bundle of paintbrushes: you're looking at a fireworm (Amphinomidae), a type of polychaete or bristly marine worm. The hairlike bristles, called setae, are hollow and contain venom. The name "fireworm" refers to the burning sensation caused when the bristles pierce your skin. This image, taken at 40x zoom, was an image of distinction in the 2008 Nikon Small World photomicrography contest.

Zooplankton in the Eye of a Needle

Credit: Peter Parks / Nikon Small WorldZooplankton are small—but do you know just how small? This drop of water smaller than the eye of a needle is magnified 20x and contains multitudes. This image took 5th place in the 2007 Nikon Small World photomicrography contest

Spaceship Mollusk

Credit: Greg Rouse / Nikon Small WorldNo, this is not an alien spaceship from another world—it is a baby file clam (Lima sp.). File clams have long tentacles that protrude from their shells—like this closely-related flame shell—which are still growing on this juvenile clam. They are used for swimming, which they do by clapping their shells together), and if a predator takes a bite, the clam can drop those tentacles to make a quick escape. The image, taken at 10x zoom, took 12th place in the 2010 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition.

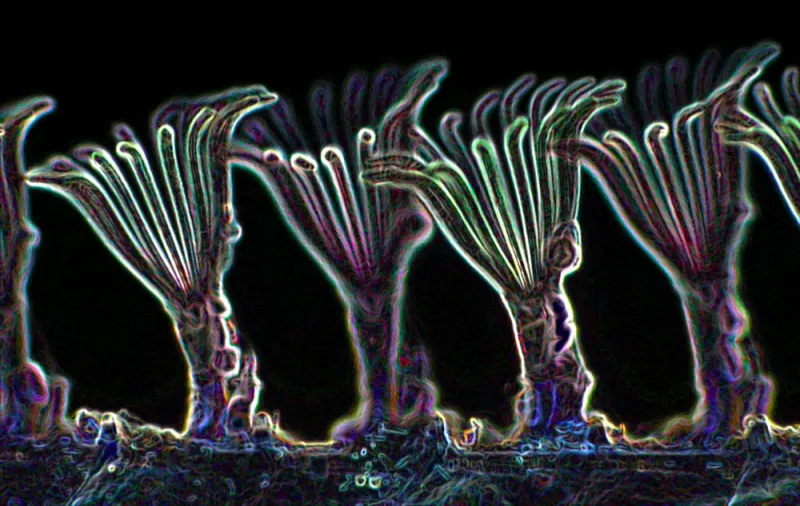

Lacy Crust Bryozoan

Credit: Bruno Pernet & Russell Zimmer / Nikon Small WorldThis colony of a lacy crust bryozoan (Membranipora membranacea) started off as just a single larva drifting in the waves that eventually settled down on a piece of kelp. From there, it budded duplicates of itself in rows, forming a colony. Lacy crust bryozoans can form large colonies covering an entire kelp blade. While they can be an important food source, in some areas (such as the U.S. East coast) they are an invasive species and can damage kelp forests. This photo, taken at 20x zoom, was an Image of Distinction in the 2012 Nikon Small World photomicrography contest.