Bringing Back Tampa Bay’s Seagrass

Back in the 1970s, if any seagrass grew beneath the shallow waters of Tampa Bay, you’d be hard pressed to notice. Thick mats of algae blanketed the water’s surface and piled high along the shores, preventing sunlight from reaching the seafloor. With no light, seagrass couldn’t grow, and without seagrass, the many animals that relied on them couldn’t grow, either.

“Many of the fishing areas that people had traditionally used no longer had fish in them,” says Holly Greening, executive director of the Tampa Bay Estuary Program. “Ibis and some of the waterbirds that feed on the small fish and shrimp and the crabs that live in the bay could no longer successfully forage, so they started to disappear.”

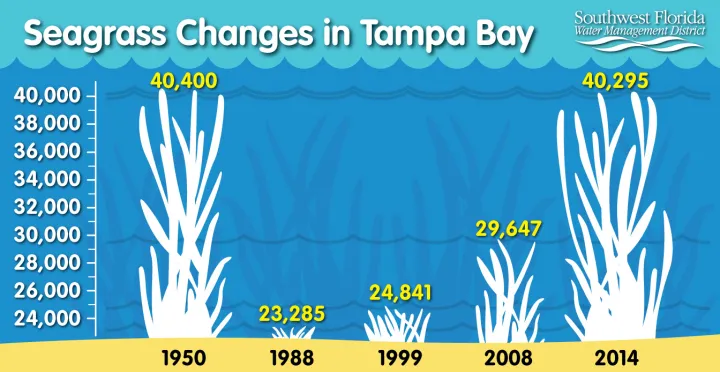

Greening has devoted herself to cleaning Tampa Bay since 1991, when the Tampa Bay Estuary Program was founded as a partnership between local, state and federal governments. By then, seagrass beds — a sign of a healthy bay — had barely started to recover from their algal smothering, thanks to the efforts of local citizens. She picked up where they left off and set what seemed like a distant goal: that Tampa Bay should support as much seagrass as it did in 1950 before pollution and algae took over. That would mean 38,000 acres of seagrass beds, nearly double the cover at the time.

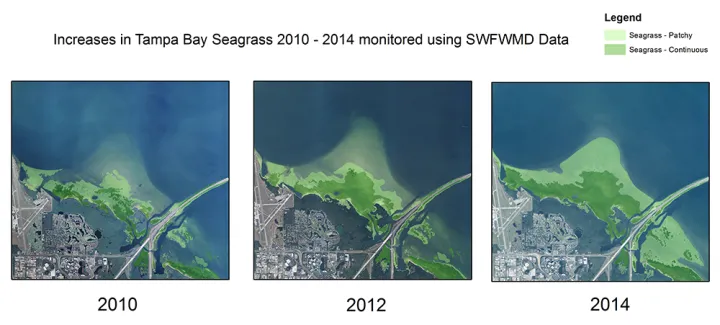

In 2015, Greening saw her goal met and surpassed: Seagrasses now cover over 40,000 acres of Tampa Bay’s seafloor, nearly twice the area of Manhattan.

The Long Road to Recovery

Today, some 2.3 million people live in the counties bordering Tampa Bay — that’s nearly six times the 1950 population of around 400,000 people. Back then, it wasn’t a very comfortable place to live. In the summer, the air is hot and muggy, and the wet season’s frequent rains cause flooding. Then a new invention brought people in droves and transformed Tampa Bay: the air conditioner.

“Once air conditioning got going in Florida in the 1950s, we really started to significantly develop our shoreline,” says Kris Kaufman, senior environmental scientist with the Southwest Florida Water Management District who works with Greening. Once people could create cool, comfortable indoor spaces to escape the heat, Tampa Bay’s population ballooned, surpassing 1 million people by 1970. To build homes with beautiful ocean views, developers uprooted mangrove forests and relocated seafloor silt — and the seagrass growing from it — to create stable land for construction along the shore. “That started the physical destruction of seagrass,” says Kaufman.

Soon another threat to seagrass arrived in the form of algae, those tiny plant-like organisms that given the right conditions can grow quickly and overwhelm watery habitats. In the early 1970s, polluted water from people’s toilets, showers and sinks was dumped straight into waterways, which then flowed into Tampa Bay. The mangroves and coastal wetlands that would have cleaned nutrients from the water had been destroyed by developers. Bathed in nutrients (like nitrogen and phosphorus), algae grew quickly and formed mats thick enough to shade out seagrass on the seafloor, killing it. “Seagrass is like any other plant; it needs sunlight to survive,” says Kaufman. “When you have these massive blooms, you can’t get sunlight down to seagrass.” By 1982, only 21,600 acres of seagrass survived.

A Community Effort

Soon the smelly algal mats piled high along the shore. “It just stank,” says Greening. Residents derided the smell wafting into their homes, and environmental advocates grew angry. In 1974, Tampa Bay was featured on the television news program 60 Minutes as the poster child for the effects of nutrient pollution. “It was an embarrassment,” says Greening. “That really helped to focus the community on: We have to do something.”

And so citizens called for action. Residents and environmental advocates demanded that local politicians do something about pollution in the bay. In 1978, the Florida state legislature passed the Grizzle-Figg Act, which set high standards for area wastewater treatment plants. Plants could no longer dump raw sewage directly into the water; instead they had to employ new technologies that scrub nutrients from wastewater before returning it to the bay, or reuse dirty water for irrigation or other industrial purposes instead of dumping it.

Three years later, when the upgrades were complete, 90 percent less nitrogen flowed into Tampa Bay. “It was like turning off a tap of nutrients,” says Greening. Five years later, the water began to look a bit clearer. “But it really took until about 1990 to see the seagrasses come back again,” she says. By then, seagrasses covered 25,200 acres of Tampa Bay — a small increase, but the first positive change seen in a long time.

In 1991, the Tampa Bay Estuary Program was founded to continue the work of cleaning up the bay. Greening, the program’s senior scientist at the time, and her staff surveyed Tampa Bay residents and found that they wanted three changes in the bay: clearer water, better fishing, and algae-free swimming.

“All three of those things pointed to seagrass as an indicator of a healthy bay,” says Greening. Seagrasses need clean, clear water to grow. They support sportfish like spotted seatrout, redfish, and snook, and make excellent fishing grounds. And cleaning nutrients from the water reduces algae blooms and helps seagrass, too.

The group then formed the Nitrogen Management Consortium, which brought together the region’s industries, farmers, businesses and local governments to keep nutrients low. Electric plants stopped burning coal to reduce nitrogen pollution carried from air into water. Farmers adopted new technologies to keep fertilizers out of waterways. Several counties ban lawn fertilizers during the rainy season. Overall, the consortium has implemented more than 500 projects that reduce nutrients in the bay, Greening says.

Their efforts have paid off — for seagrass, wildlife, and area businesses. In 2015, seagrasses stretched across more than 40,000 acres of Tampa Bay, surpassing their cover in 1950 before the problems began. The water is cleaner than ever, waterbirds have returned, and fishermen report better fishing. And a recent survey found that a clean Tampa Bay supports 1 in 5 jobs in the region. “A healthy bay isn’t just good for the users of the bay but for the economy of the region,” say Greening.

Tampa Bay’s seagrass recovery took research, planning, the commitment of the community—and lots of patience. “It took nearly 30 years for our system to recover,” says Kaufman. It’s not something that can be done overnight, and even after recovery, the work continues to keep the bay healthy as the population swells.

But Tampa Bay’s success proves that recovery is possible. And people restoring seagrass beds around the United States are taking notes. “This is one of the first large-scale systems to actually see recovery,” says Kaufman. “That’s why people are so excited about this system.”

This story was made possible by a grant from the Smithsonian Women's Committee. http://swc.si.edu/about-grants