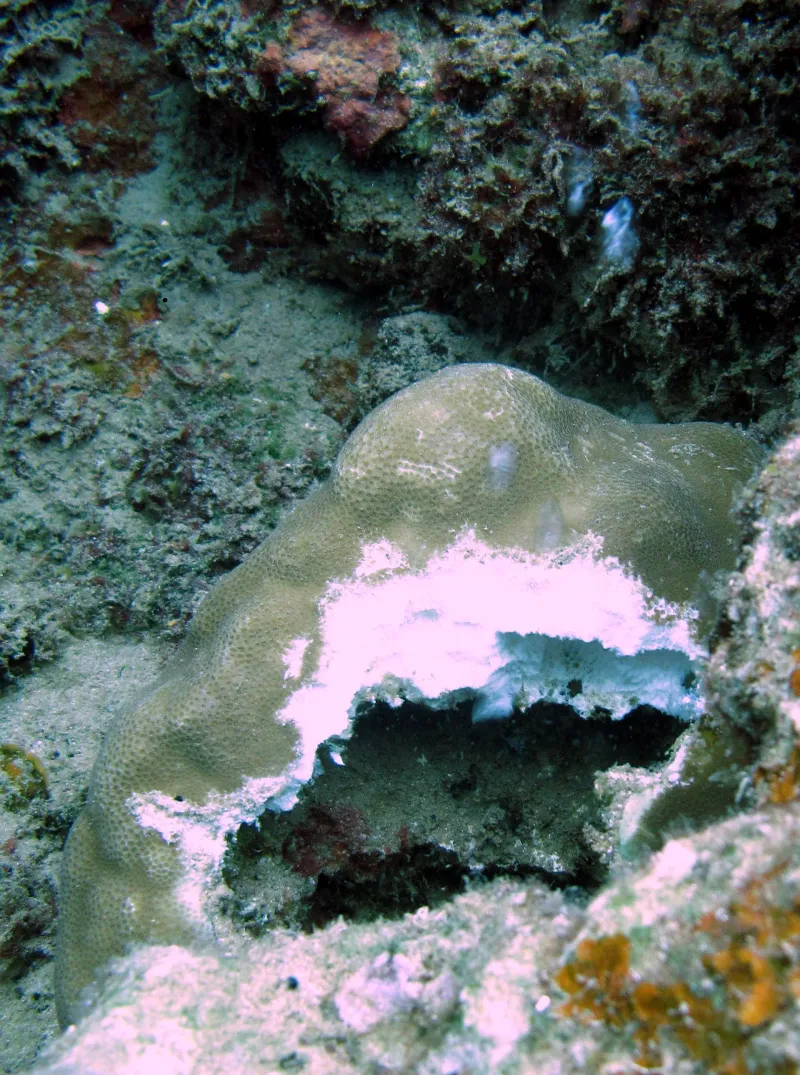

In Ili Ili Bua Bua, Normanby Island, Papua New Guinea, CO2 bubbles out of intense volcanic vents in the reef. The excess carbon dioxide dissolves into the surrounding seawater, making water more acidic—as we would expect to see in the future due to the burning of fossil fuels. The town's name, Ili Ili Bua Bua, means "Water Water Bubble Bubble" in the local dialect. Read more about how reef scientist Laetitia Plaisance uses carbon dioxide seeps to study ocean acidification.

slideshow

Will Coral Reefs Survive Acidification?

Nestled among the beautiful coral reefs of Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a place that could provide the key to our understanding of one of the biggest threats to coral reef survival: Ocean Acidification. Here cool carbon dioxide naturally bubbles out of volcanic cracks in the shallow sea floor and makes the surrounding waters more acidic. This place gives us a glimpse into the future as absorbed atmospheric CO2 makes the ocean more acidic. Smithsonian scientist, Laetitia Plaisance, uses this unique place to study what will happen to corals and coral reefs if the ocean gets more acidic. Read the full blog post from Dr. Plaisance to learn more about acidification and these amazing CO2 seeps.