Penguins

Introduction

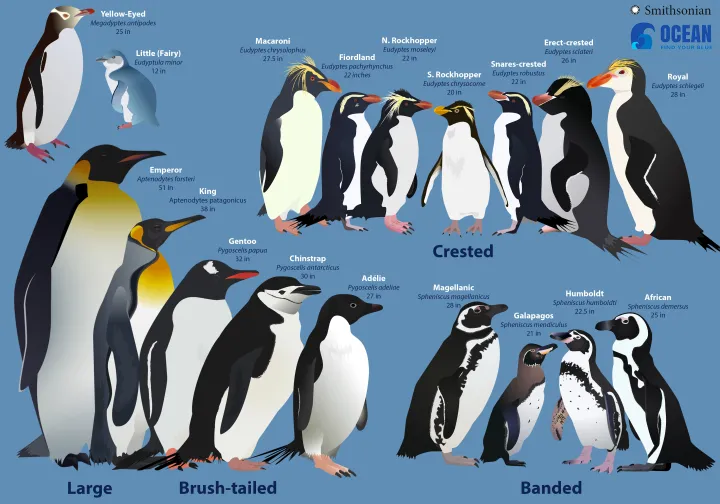

Tuxedoed birds with endearing personalities, penguins are fascinating to young and old alike. Clumsy and comical on land, they become beautifully graceful swimmers below the ocean’s waves. Although the various species of penguins look similar, the largest penguin, the emperor, stands at 4 foot, 5 inches (1.35 meters) and the smallest penguin, the fairy or little, stands at about a foot tall (.33 meters).

Contrary to popular belief, only five penguin species ever set foot on the icy Antarctic continent and only two, the Adélie and emperor, live there exclusively. In fact, penguins inhabit a very diverse array of environments. The Humboldt penguin of Chile and Peru lives on the shores of the Atacama Desert, the driest desert in the world where temperatures can reach around 70°F (21°C). The yellow-eyed penguins of Enderby Island off New Zealand burrow under the trees of the dwarf rata forests. Each penguin species is uniquely adapted to its home environment.

Anatomy, Diversity & Evolution

Anatomy

Extreme Swimmers and Divers

Penguins are birds of the ocean, spending up to 75 percent of their lives in the water. Some penguins, like the fiordland and rockhopper, have even been found with barnacles growing on their feathers! Much of what seems odd about penguins is due to the fact that they spend so much time in the water.

Swimming is what penguins do best. A penguin’s awkward waddle may seem comical on land but that’s because they are made to swim. Adaptive wizards of the sea, their torpedo shaped bodies combined with powerful flippers enable penguins to swim to considerable depths and over great distances. Their legs and feet, located far back on the body, contribute to the waddle on land, but underwater they act as streamlined rudders that minimize drag.

At the water’s surface a penguin can at best paddle like a duck, but below the waves penguins cruise at speeds faster than Olympic swimmers. The fastest, the emperor penguin, can reach 9 mph (14 km/hr) when in a hurry but prefers a steady 7 mph. Most midsize penguins swim around 5 mph (8 km/hr) and the smallest penguin, the little penguin, meanders at a slow 1 mph (1.5 km/hr). A traveling penguin keeps the surface within 3 to 6.5 feet (1-2 meters) often employing a swimming technique called porpoising. Porpoising is a shallow skimming across the water through a series of consecutive leaps, named for its similarity to how porpoises swim. The primary function of porpoising is its efficiency in moving quickly through the water while allowing for breathing at the surface without slowing down. It may also serve as a defense mechanism against predators—it makes it difficult to grab a swimming penguin when they are continually disappearing above the surface.

On average, penguins dive to depths between 30 and 60 feet (9 and 18 m). The smaller species of penguin tend to feed at the surface of the water, but larger penguins like the king penguin frequently dive to 300 feet (91 m), and emperor penguins can reach depths around 1,700 feet (518 m). A 2018 study measured an emperor penguin diving for over 32 minutes—the longest recorded avian dive to date.

The wings of a penguin, once used for flight by their distant ancestors, are powerful swimming propellers. Shorter wingspans, along with flattened, fused and dense bones devoid of air pockets, distinguish penguins from flying birds. They also have two sets of strong flipper muscles, much like human biceps and triceps, which generate power while swimming. Unlike flying birds, which rely on the propulsion of the downstroke for flight, penguins gain momentum underwater from both the downstroke and the upstroke. In response to the high density of water compared to air, penguins have also developed an array of strong chest and back muscles. One muscle, the scapulohumeralis caudalis, attaches to the scapula (or shoulder blade) and supplies the power to lift the wing. Most birds require only small and thin scapulas to support the wings but penguins require larger scaffolding for their swimming muscles. The penguin scapula has evolved to be much broader, similar in shape to a tapered tennis racket.

The adorable tuxedo serves a purpose in the water as well. Called countershading, the black and white coloration helps camouflage the birds from potential predators. When seen from below a white belly better blends in with light-filled surface waters while from above a black back looks similar to the dark hues of the deep ocean.

Marine creatures that live in the sea but rely on freshwater to survive often develop special adaptations that filter out excess salt. When a penguin feeds it often consumes significant amounts of seawater. To get rid of the unwanted salt, penguins evolved a special gland that filters seawater. The supraorbital glands, or salt glands, lie on either side of the beak in a v-shaped groove above the eye and are surrounded by a network of blood vessels and nerves. The salt is excreted over the beak and then a quick “sneeze” and shake rids the beak of the salt.

Fabulous Feathers

Penguins live in some of the harshest climates, from the frozen plains of Antarctica to the equatorial heat of the Galapagos, and they immerse themselves in the ocean for months at a time. So it should be no surprise that they evolved a highly efficient protective layer that shelters them from the environment.

A penguin’s feathers serve to regulate body temperature, increase aerodynamic efficiency underwater, and defend against the elements. Beyond providing insulation, feathers can also minimize drag by trapping bubbles against their body and then releasing them during a dive. A diving penguin emits a visible trail of bubbles as it moves through the water. Penguins take great care of their feathers, often preening three hours a day. An oil secreting gland, the uropygial gland, lies at the base of a penguin’s tail and dispenses water-repelling and microbial deterring oil that a penguin then physically spreads over its body.

Most bird’s feathers are arranged in parallel tracks, but this distribution leaves featherless gaps. Penguin feathers by comparison are continuously spaced across the penguin’s skin. Until recently it was believed that penguins had the highest feather density of all birds, but a 2015 study revealed emperor penguin feather density averaged around 9 feathers per centimeter, less than a fourth of what was previously believed. In addition to the contour feathers that line the birds entire body and help give it shape, penguins also have after-feathers (fluffy, downy bits that cling to the contour feathers), plumules (down feathers that attach to the skin), and filoplumes (microscopic feathers with barbs on the end). The individual function of each feather type is still unclear, but plumules are nearly four times more numerous than contour feathers, leading scientists to believe they serve an important purpose.

Considering penguins live at varying latitudes it should follow that different species exhibit variations in their feathers. All penguins maintain a body temperature between 100 and 102 degrees Fahrenheit (around 38°C) but they live in temperatures that range from 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32°C) along the coast of Patagonia to negative 76 degrees Fahrenheit (-60°C) on the sea ice of Antarctica. Feathers account for nearly 85 percent of a bird’s insulation, and when the weather is warm that insulation can make temperatures a bit toasty. The banded penguins, such as the Humboldt and African penguins, have featherless patches on their faces and feet where they divert blood to cool when overheated. In contrast, the Adélie penguin, one of two Antarctic species, has complete feather coverage up to the base of its beak.

Although feathers can be fluffed up or flattened down, penguins also use other methods to keep their temperatures at the right level. When an Adélie penguin overheats it diverts blood to its thin wings, causing the white undersides to turn a faint pink color. When cold, penguins rely on countercurrent exchange to warm up, a specific heat transferring mechanism that exchanges heat from warm blood traveling in vessels towards their legs and feet to colder blood leaving the area.

Senses

Many aspects of the senses of penguins also reflect their sea-going habits.

VISION

Penguins need to see clearly both on land and underwater. Terrestrial animals, including humans, rely on the cornea—the clear outer layer of the eye—to focus images using a property called refraction, a bending of light as it crosses through different materials. As light travels through the air and enters the eye, it bends to the appropriate angle and creates a focused image on the retina. Underwater, terrestrial animals become far-sighted because the fluid of the eye and the water are too similar, so the light doesn’t bend enough and the image doesn’t focus effectively. Penguins solve this problem with a flattened cornea and highly modified lens. Their flattened corneas have less refractive power than those of terrestrial animals, enabling them to see clearly underwater. Their spherical lenses can compensate for the flatter cornea by also bending the light.

The king penguin’s eyes are unique even among penguins. When fully constricted the pupil appears as a pin-sized square but in low light conditions it will expand an amazing 300 fold—the greatest change in pupil size of any bird—to increase light reception. This is especially important when king penguins dive to their greatest depths, around 984 feet (300 meters). The contrast in light is equivalent to bright sunlight and starlight. Because maximum foraging depths can be reached in five minutes, there isn’t enough time for the retina to adapt to the changing light. By constricting the pupil to a pinhole in sunlight the retina is pre-exposed to the lower ambient light levels found at maximum dive depths where the pupil then fully expands.

Adapted to underwater conditions, penguins have shifted their visual light spectrum in favor of violet, blue, and green and to exclude red, a color that quickly disappears at depths greater than 10 feet (3 meters). It is thought that penguins can even see ultraviolet light—emperor and king penguin beaks reflect ultraviolet rays, the only marine birds to do so. The display of ultraviolet could contribute to mate selection with both females and males preferring mates with stronger displays of ultraviolet reflectance.

HEARING

Like other birds, penguin ears lack external ear flaps. The ears reside on either side of the head as holes covered by feathers. As any SCUBA diver knows, pressure changes from diving can damage the fragile structures within the ear. A study of the king penguin ear showed that their middle ear is protected from pressure changes during diving by a special organ made of cavernous tissue. When ambient pressure increases the tissue expands into the middle ear to maintain a constant pressure.

In the cacophony of hundreds of penguins on land a returning parent can pin point their chick from the rest of the colony based on its unique call. One study of African penguins found their hearing range to be between 100 and 15,000 Hz, but peak sensitivities were between 600 and 4,000 Hz—in comparison, humans hear between 20 and 20,000 Hz.

An acute sensitivity to sound may be a defense penguins employ in the face of predators like orcas and leopard seals. One study showed even when asleep, king penguins could distinguish between predatory sounds and harmless sounds. In the presence of an orca call penguins flee upon awakening. Similar to migratory birds, penguins may rest only one half of their brain while the other stays vigilant, constantly monitoring the surroundings for possible threats.

TASTE

Penguins have poor taste reception, similar to most birds. A recent study showed penguins lack the sweet, bitter and umami taste receptor genes, maintaining only salt and sour. Most birds only lack sweet. It is believed that the cold temperatures of Antarctica, where modern penguins evolved, contributed to the loss of these tastes as sweet, umami and bitter taste receptors function poorly in cold temperatures. Penguins also lack taste buds on their tongue, leading scientists to question whether penguins can taste at all.

SMELL

The olfactory lobe in the brains of penguins is relatively large. Historically it was believed that penguins possessed a rudimentary sense of smell but recent studies indicate smell may play a larger role in a penguin’s life than previously thought. Studies of African, Humboldt and chinstrap penguins indicate some penguins can detect prey using olfactory cues such as chemicals released by foraging krill. The Humboldt penguin uses smell to distinguish between related and unrelated individuals and to find mates.

Diversity

Penguins claim their own family, the Spheniscidae family, and are likely most closely related to other birds like the petrel and albatross. There is still debate over the number of distinct species, but it is generally agreed that there are between 17 and 19 species (see rockhopper and little penguin sections for more information). The species are divided among six genus divisions, or genera, commonly referred to as the crested, banded, brush-tailed, large, yellow-eyed, and little.

1. Crested Group (Eudyptes)

Macaroni (Eudyptes chrysolophus)- Macaroni penguins are the most abundant of all the penguins. The most southerly distributed crested penguin, they live along the coasts of sub-Antarctic islands and the Antarctic Peninsula. The lifespan of a Macaroni penguin spans from 8 to 15 years. Macaroni prefer krill but will also eat small fish and squid. They are roughly 27.5 inches (70 cm) in height and between 8 to 14 pounds (3.7-6.4 kg) in weight.

Royal (Eudyptes schlegeli)- The royal penguin differs from other crested penguins in its orange plumage instead of yellow and white face. Some still argue that it is a white-faced variant of the Macaroni penguin due to genetic similarities but others point to distinct ecological differences and breeding isolation. Breeding is restricted to Macquerie Island off New Zealand and begins in October. Chicks take 35 days to hatch and become reproductively mature themselves after 5 to 6 years. Individuals can live between 15 and 20 years. They mostly eat krill but supplement their diet with small fish. Royal penguins stand at 28 inches (70 cm) and 8.8-12 pounds (4-5.5 kg).

Fiordland (Eudyptes pachyrhynchus)– Fiordland penguins have the characteristic yellow tufts of feathers like other crested penguins and live along the temperate rainforests of South Island and Stewart Island of New Zealand. Unlike many penguin species, they prefer to nest isolated from other mating couples. The birds nest under forest canopy, in caves, under boulders and shrubbery, and in nests made of brush and grass. They eat fish larvae, crustaceans and squid. Breeding season begins mid-winter in July and egg incubation ranges between 4 and 6 weeks. Adults stand 22 inches (55 cm) at between 5.5 and 10.75 pounds (2.5-4.9 cm) and live to be up to 20 years old.

Rockhopper (Eudyptes chrysocome)- The rockhopper penguin is further divided into three subspecies, the Northern, Southern and Eastern rockhoppers, and is the source for much of the debate surrounding the total number of penguin species. They live on small, isolated islands in the sub-Antarctic regions of the Atlantic and Indian oceans. Rockhopper nesting grounds are on rugged terrain requiring the penguins to hop from rock to rock, the inspiration for their name. The birds can congregate in colonies containing up to 100,000 individuals. Breeding season begins in October, eggs are laid by November and chicks hatch 33 days later. The average rockhopper lives 10 years, but they may live as long as 30 years. They feed on krill, small fish and squid. Rockhopper penguins are the only species to jump feet first into the water when they dive. They stand at 18 inches (46 cm) and weigh 5 to 10 pounds (2.2 to 4.5 kg).

Snares Crested (Eudyptes robustus)-Snares crested penguins live on the isolated and densely forested Snares Islands, a group of small islands roughly 60 miles (100 km) south of New Zealand. They inhabit the most restricted area out of all the penguins and eat squid and small fish. The birds breed under the protection of the Olearia forests in nests of peat, pebbles, and brush beginning in September. Two eggs are laid a few days apart and hatch between 31 and 37 days later. Snares crested penguins reach sexual maturity at age 6 and may live up to their early 20s. They stand at 22 inches (56 cm) and weigh between 6 and 10 pounds (2.7 to 4.5 kg)

Erect-crested (Eudyptes sclateri)- The erect-crested penguins are best identified by their upright and fanned yellow plumes. Colonies exist on the islands off New Zealand including Bounty and Antipodes Islands. Male competition for breeding sites in September is fierce and penguins commonly resort to biting and beating each other with flippers. The diet of erect-crested penguins is not well known, though it is suspected they eat krill, small fish, and squid like other crested penguins. They stand at 26 inches (67 cm), weigh up to 14 pounds (6.4 kg) and live up to 15 to 20 years.

2. Banded Group (Spheniscus)

Humboldt (Spheniscus humboldti)- Native to the hot climate of the Atacama Desert on the coast of South America, Humboldt penguins have large, bare skin patches around their eyes, an adaptation to help keep them cool. Humboldt penguins dig nests in sand or penguin poop (guano) where they incubate the eggs for 40 to 42 days. Breeding season is either March to April or September to October depending on the location of the colony. Humboldt penguins rely on the nutrient rich Humboldt Current to support the anchovy and sardine populations they prey upon. The Humboldt is one of the most popular zoo penguins due to its ability to withstand warmer climates. They stand at an average height of 25.5 inches (65 cm) and weigh between 8 and 13 pounds (3.6-5.8 kg).

Magellanic (Spheniscus magellanicus)- The Magellanic penguin lives along the southern coast of South America from Argentina on the Atlantic side to Chile in the Pacific. Their breast plumage consists of two black stripes that differentiate them from the geographically nearby Humboldt penguin. Magellanic penguins nest in ground dugouts, when possible, or under brush. Both parents share sitting on the egg for the 39 to 42 day incubation period. During the winter months, between May and August, Magellanic penguins migrate along the coast of Chile, and as far north as Brazil on the East Coast, chasing anchovies. Adults stand at 28 inches (70 cm) and weigh up to roughly 15 pounds (6.5 kg).

African (Spheniscus demersus)- The African penguin is sometimes referred to as the jackass penguin for its shrill braying that sounds like a donkey. They inhabit the southern shores of Africa from Namibia to South Africa and feed on pilchard, sardines, anchovies, and mackerel. Their nesting colonies are large and noisy. Each breeding couple lays two eggs in a shallow dugout in the ground. Eggs are incubated between 38 to 40 days by both parents. They have a lifespan between 10 and 15 years. At 23 to 25 inches tall (58-63.5 cm) and weighing between 5 and 9 pounds (2-4 kg) they are one of the smaller penguins. As of 2024, the African penguin is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN.

Galapagos (Spheniscus mendiculus)- Galapagos penguins are the most northerly penguins, living along the Galapagos Islands on the equator. These penguins have special adaptations and behaviors that help them deal with the tropical heat. Galapagos penguins actively seek out shade, pant, stand with wings spread, and hunch over on land to shade their feet, an area of heat loss. Galapagos penguin breeding is completely dependent upon the Cromwell Current and they may breed during any month of the year depending upon seasonal climate conditions. When the Cromwell Current fails to upwell and bring colder, nutrient rich water to the surface, penguins delay breeding presumably because of low food availability. The highly variable climate is influenced by the unpredictable El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Once the penguins are able to breed, egg incubation is roughly 40 days. The Galapagos are the smallest of the banded penguins at 21 inches (53 cm) and weigh up to 5.5 pounds (2.5 kg).

3. Brush-tailed Group (Pygoscelis)

Chinstrap (Pygoscelis antarcticus)- Chinstrap penguins are distinguishable by their white face and a thin black band that runs across the chin. Unlike many other penguin species, the chinstrap usually rears both chicks to adulthood when environmental conditions are favorable. They nest on the Antarctic Peninsula and sub-Antarctic Islands in the South Atlantic on rocky terrain. Beginning in November, adults incubate the eggs in shallow pebble nests for up to five to six weeks. They prey upon Antarctic krill, Euphasia supurba, almost exclusively but will also eat small fish. At a maximum size of 30 inches (76) and weighing 10 pounds (4.5 kg), they are medium-sized penguins.

Gentoo (Pygoscelis papua)- The largest of the brush-tailed penguins, this bird is further distinguished by its red beak. The gentoo nests on both the Antarctic Peninsula and on sub-Antarctic islands. They construct nests with tussock grass and moss when available but will also use pebbles in rockier environments. Both eggs are incubated for 31 to 39 days. Loyal birds, they not only return to the same nesting site every year but will also form lasting bonds with breeding partners. Adults subsist on mostly Antarctic krill but will also eat other crustaceans, squid, and fish. Gentoo penguins reach sizes up to 32 inches (81 cm) and 15 pounds (6.5 kg).

Adélie (Pygoscelis adeliae)- The Adélie penguin is one of two penguins to nest exclusively on Antarctic shores, the only other penguin to do so is the formidable emperor penguin. An ice-dependent species, they rely on the ice for foraging, often trapping prey under ice floes (sheets of ice that jigsaw the ocean surface) and resting on top of them to avoid predators. Populations are on the decline on the northern Antarctic Peninsula, where air temperatures significantly increased in the latter half of the 20th century due to climate change. Breeding season begins in October, with eggs hatching after 35 days of incubation. They rely heavily on Antarctic krill but also eat fish, crustaceans, and other krill species. The birds stand at 27 inches (70 cm) and weigh up to 12 pounds (6.5 kg).

4. Large Group (Aptenodytes)

Emperor (Aptenodytes forsteri)- Living exclusively within the Antarctic, emperor penguins are truly animals fit for the extreme. To enable chicks the best chance of survival, adults incubate the egg in subzero conditions (some days hit -40 degrees Fahrenheit/Celsius) during the dead of winter. Breeding season begins at the end of March with couples congregating in one of 45 different colonies along the Antarctic sheet ice. After a quick courtship, females lay a single egg and transfer it to a nest between the feet of the father. The egg will sit on the father’s feet for roughly two months while the mother returns to the sea to feed on fish, krill, and squid. Father emperors battle harsh temperature and wind conditions while incubating the egg. They often lose as much as half their body weight during the process. At a maximum size of 51 inches (130 cm) and 88 pounds (40 kg) they are the largest penguin species.

King (Aptenodytes patagonicus)- Lasting between 14 to 15 months, the king penguin’s breeding cycle is the longest of any bird. Adult couples can only afford to raise two chicks every three years because of the extensive time needed to rear one chick. Breeding may begin anywhere from November to April so colonies have a mix of chicks of various ages. King penguins breed on sub-Antarctic islands within the Southern Atlantic. Standing they can reach heights up to 38 inches (95 cm) with weights as high as 35 pounds (16 kg).

5. Yellow-Eyed (Megadyptes antipodes)- Yellow-eyed penguins are the most private of all penguins, preferring to nest out of sight from other penguins. They often forgo parental duties if they are within eyesight of other nesting couples. For this reason they often nest among the tree trunks of the dwarf rata forests on the islands off of New Zealand where they are native. The breeding season is particularly long, lasting from August to February. Egg incubation alone can take up to two months. They weigh between 5 and 5.5 pounds (2.3-2.5 kg) and reach heights of 65 cm (25 inches).

6. Little Penguins (Eudyptula)

Little or Fairy (Eudyptula minor) – The smallest of the penguins, the little penguin claims the rocky island coasts around New Zealand and Australia as home. Colonies are usually at the base of sandy dunes or cliffs. They eat mostly small fish, but occasionally will consume krill and small squid. Little penguins live an average of 6.5 years though they have been known to reach ages as high as 20. Breeding season begins in August and lasts until December. Chicks take roughly 36 days to hatch and then another 3 to 4 weeks where they depend on their parents for food. Juveniles reach sexual maturity at age three. They weigh in at a mere 2 to 3 pounds (.9-1.4 kg), and stand only 12 inches (24 cm) tall.

Evolution

The first penguins evolved roughly 60 million years ago in temperate latitudes around 50 degrees South, close to where New Zealand is now. An area devoid of land predators, the location lent itself to the survival of flightless birds. While many birds nest in trees or cliffs to protect their chicks from wild mammals, penguins historically have been able to nest on the ground without the threat of large predators. Without the constraints of flight, namely the weight and wing surface area necessary for lift-off, penguins could claim a new domain—the ocean.

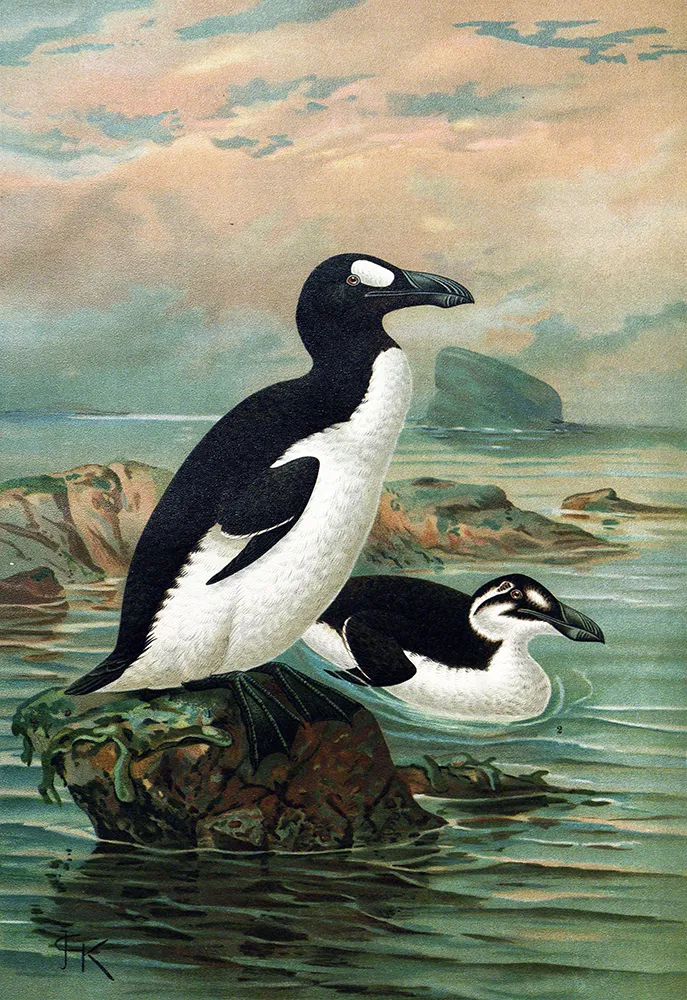

Penguins are Southern Hemisphere birds, though many people confuse them with the black and white birds of the north, the puffins. The term penguin is thought to have originated from either Welsh “pen” and “gwyn” for white head or the Spanish pingüino, referencing excessive amounts of fat. The first bird to go by the name was actually the now extinct great auk which was a black and white flightless bird in the northern Atlantic. The great auk is in no way related to modern penguins, instead claiming membership in the Alcidae family, same as puffins, other auks, and murres. In the 1800s, fishers and whalers slaughtered the flightless great auks by the thousands to supply food aboard ships, and by 1844 the species was extinct. Their memory seemed to stick with seamen, for when explorers traveled to the southern seas and encountered new tuxedoed birds they repurposed the name.

Scientists of the early twentieth century believed penguins were a living link between birds and dinosaurs. This belief spurred the famous Worst Journey in the World, a scientific expedition led by Dr. Edward Wilson in 1911 that aimed to retrieve emperor penguin eggs for the purpose of studying the embryos. At the time it was still believed that early developmental stages directly reflected attributes of previous ancestral stages; in the case of penguins, reptilian scales in the embryo could be evidence of dinosaur lineages. This connection has since been disproven, although all birds are indeed now recognized as having evolved from dinosaurs.

The earliest known penguins evolved shortly after the demise of the dinosaurs in the Cretaceous-Tertiary mass extinction. Roughly 66 million years ago species from the genus Waimanu lived in the waters off of New Zealand. The two species of Waimanu penguins are currently considered the basal ancestors, meaning they are considered the earliest common ancestor of all penguins. Flightless like modern penguins, Waimanu penguins still maintained anatomical similarities to flying birds and may have had swimming capabilities similar to a loon or cormorant. Their beaks were long and slender and their legs were slightly larger than the modern penguins. The discovery of these ancient penguins was based on an analysis of four separate specimens from North Canterbury, New Zealand that are some of the best-preserved avian fossils from that era. It was these specimens that supplied evidence for the theory that penguins split from other birds before the end of the Cretaceous epoch.

By 60-55 million years ago penguins were well adapted to life at sea. Not only were there roughly 40 species, more than twice the number today, but they also grew to be much larger sizes. The heaviest of these penguins, Kumimanu fordycei, lived 60 million years ago along the shores of what is now New Zealand. At roughly 350 pounds this massive penguin was about the size of a small bear. Its wings were still primitive flippers more similar to today's puffins, indicating it still retained some remnants of its flying ancestors.

From 40 to 25 million years ago giant penguins adapted to life at sea were the dominant predators of squid, fish, and krill. The tallest of these giant penguins, Palaeeudyptes klekowskii, lived roughly 37 million years ago and measured 6 feet 6 inches (2 meters) from beak tip to toe. It would measure close to the average height of an adult woman at 5 foot 3 inches (1.6 meters) when standing. By comparison, today’s emperor penguin is 4 feet 5 inches (from top of head to toe). Described in 2014 by an Argentinian research team, P. klekowskii is the most complete Antarctic penguin skeleton discovered to date.

Around the same time period—but farther north—the Peruvian giant, Icadyptes salasi, stood at a slightly shorter 5 feet. This giant supported a unique 7 inch beak that is theorized to have been helpful in spearing fish. The discovery of this fossil upended previous conceptions about the equatorial migration of penguins. It was thought that penguins migrated north towards the equator after periods of Earth cooling like that which occurred during the Eocene-Oligocene (around 34 million years ago) and a later cooling period 15 million years ago. But the earlier migration of Icadyptes indicates penguins actually migrated during a time of significant warming.

By 23 million years ago, during the early Miocene, most of the giant penguins had long died off, all except Anthropodyptes gilli. This giant was still thriving in Australia until 18 million years ago. After the fall of the giant penguins, it is believed that the crested penguins, the ancestors of all modern day penguins, radiated from a common Antarctic ancestor. Genetic analysis of four penguins and recent discovery of penguin fossils indicate a common ancestor as early as 20 million years ago with individual modern species diverging between 11 and 16 million years ago. Scientists still debate the evolutionary origins of modern penguins and this is an ongoing area of research.

Ecology & Behavior

Movements

During breeding season penguins stick close to the colony, but how far a penguin travels to feed varies from species to species. Most penguins will stay within 36 miles (60 km) of shore. Gentoo’s and yellow-eyed penguins will only forage for 12 hours, whereas the emperor penguin, which breeds in the less productive winter months, can forage for months at a time. After fasting for months while incubating the egg, a male emperor may need an entire month to regain its body fat, possibly traveling up to 950 miles (1,529 km).

Once penguins leave breeding colonies after the breeding season, our understanding of their behavior and ecology drops precipitously. Tags often lose satellite connection mid-migration, possibly due to batteries losing power or tags falling off. But certain case studies reveal that penguins regularly make long migrations to feed in the winter and thus recondition their bodies post-breeding. Magellanic penguins, native to Argentina and Chile, have been spotted as far north as Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. One study tracked ten Magellanic penguins as they swam up the Argentine coast and recorded traveling distances over 1,118 miles (1,800 km) from the nest. When total swimming distance was calculated the penguins swam more than 1,678 miles (2,700 km). In another study a chinstrap penguin was logged traveling 2,237 miles (3,600 km) in three weeks in the Southern Atlantic from Bouvetoya to Montagu Island in the South Sandwich Islands, a cluster of islands between Antarctica and Argentina. Macaroni penguins from the Kerguelen Islands in the Indian Ocean traveled an average of 1,553 miles (2,500 km) to foraging grounds in the middle of the ocean. The Fiordland Penguins have them all beat—one study found that these penguins make an epic 4,000-mile (6437 km) round-trip journey in just over two months. Beyond isolated studies of a few individuals it is still unclear what an average penguin migration distance or destination may be.

Reproduction

Every year penguins assemble in loud, crowded and smelly colonies for one reason—to mate. Most penguin species gather once a year, with the exception of the Galapagos and king penguins, in order to breed and raise chicks.

The male usually arrives first in order to reclaim prime nesting sites from years past or establish a new one. A shallow dugout in the ground or a pile of stones serves to protect eggs and chicks from the elements, whether that is the sun, wind, snow or rain. Dominant chinstrap penguins will often steal scarce pebbles from less experienced males to build up their nest, which is important considering one study found that 14 percent of chicks drowned in flooded nests after a storm, with the majority of the deaths occurring in smaller nests. When a nest works, penguins remember and return to tested and proven nests in later years. A study comparing the penguins of the Pygoscelis genus—gentoos, chinstraps, and Adélies—showed 63 percent, 94 percent and 99 percent nest return rates respectively from the previous year. Emperor penguins and king penguins are notably different than all other penguins; they forgo a nest altogether and instead carry a single egg on the tops of their feet.

A female arriving at the colony has a few decisions to make. She can either return to her mate from previous years or shop for a new one. Females want the most physically fit mate in order to give their offspring the best chance of survival. A study of one Adélie penguin colony found that 17.3 percent of chick losses were from a parent deserting the nest due to starvation. Most returning mates arrived only a few days after the other parent deserted the chicks and the loss could have been avoided if the parent could hold out for a little longer. In the waiting game, it’s advantageous to be a large, fat penguin. Emperor penguins that breed on the Ross Ice Shelf have a bit of an advantage since they are within close distance to the ocean and males have been observed making ventures for a quick snack during the courting period. Beyond obvious physical appearance, a female penguin will also look for low and deep vocal calls since a deep voice usually means the male is larger.

Feather color is another indicator of male health. Birds in general display the health of their immune systems in what is called an honest signal. Color for feathers is costly since the yellow orange pigments, carotenoids, are also used within the immune system to fight infection. Bright plumage means a healthy bird. However, historically this principle was found in sexually dimorphic birds, where males and females are physically different. Penguins are monomorphic, it’s even difficult for experts to tell the sexes apart. Even so, experiments where king penguin plumage was altered showed that the altered feather colors significantly reduced the ability of males to pair with a mate but not females.

Once a pair decides to mate, a series of courting behaviors follow, cementing the bond that will carry them through the trying months of parenthood. Vocal duets of screeching calls create an ear-splitting chorus at colonies during this time. Preening and grooming each other is common, possibly as a way to rid partners of harmful parasites that could be detrimental later during the period of chick rearing. Penguins will also bow their heads in a passive stance with bills tucked, a vulnerable position that increases the pair bond strength. Courting ends when the female sprawls on her stomach to entice her partner and the male mounts the female’s back to copulate.

Penguins usually lay two eggs, with the exception of the king and emperor, which only lay one. There are a few days in between the laying of the first egg and the second, in what is called asynchronous hatching. The crested penguins will eventually only raise one chick; the second egg may not even hatch or in some cases the smaller chick will be ignored by the parents and eventually die (which is often the case for Macaroni penguins). The second egg, called the “B” egg, can be up to 70 percent larger than the first laid egg, the “A” egg. It is the B egg that typically survives. In all penguin species, the egg is incubated in a special featherless brood pouch that keeps the egg warm. Most penguin mates share egg incubations that can last between 33 and 56 days, depending on the species. The notable exception is the emperor penguin. The male emperor incubates the egg in the dead of winter for roughly 64 days huddled with other males while the females forage.

A chick is equipped with several tools to escape the strong egg when the time comes to hatch. An egg tooth, a sharp bump on the top of the bill, is used to crack the egg. They also have strong neck muscle that provides the force to break the shell. Both the egg tooth and the hatching muscle disappear shortly after hatching. When chicks are older in the “post guarding phase” and both parents are at sea foraging for food chicks will huddle in groups called crèches to keep warm and avoid predators. Chicks and parents find each other amid the chaos of crèches through individualized calls that act like an auditory signature.

After 2 to 4 months, chicks become independent. When they molt their baby feathers or down they are equipped to enter the water and begin life on their own.

In The Food Web

Penguin diets consist mainly of krill, squid, and fish. The macaroni penguin is the single largest consumer of marine resources among seabirds, with 9.2 million tons of prey being consumed annually. With such a high demand for food, penguins tend to form colonies near highly productive waters. Upwelling brings cold, nutrient rich waters to the surface where phytoplankton (at the base of the food chain) bloom and feed the fish, krill, and squid that penguins eat. The Galapagos penguin relies on the Cromwell Current just as the Humboldt penguin relies on the Humboldt Current for productive waters. On the West Antarctic Peninsula deep ocean currents come in contact with the jutting land mass and upwelling of nutrient rich waters feeds large populations of krill, a favorite food of the Adélie penguins. Preliminary research indicates Adélies in this region of upwelling nest near deep basins, where they can count on nearby access to prey every year.

In parts of the Southern ocean (the western Antarctic Peninsula and where the continent meets the South Atlantic Ocean), the diet is dominated by Euphasia superba, the Antarctic krill. These krill measure roughly three inches (7.6 cm) in length and travel in large, synchronized schools. To catch a single krill, penguins circle the school, condensing them until some of the krill break away from the group, at which point a penguin swoops in from below. A penguin’s tongue, though lacking taste buds, has large keratinized bristles that help grip the krill or fish as it enters the mouth.

Although on land an adult has little to fear, in the water the penguin’s predators match their underwater speed. The most impressive predator, the leopard seal of Antarctica (Hydrurga leptonyx), is an agile 1,102 pounds (500 kg) eating machine that grips the penguin with its one-inch canines and thrashes it against the water’s surface. Killer whales (Orcinus orca) are another prominent predator of penguins. They will often stalk penguins resting on ice floes in Antarctica or hunt off the shores of penguin colonies in the Southern Atlantic. Occasionally the Southern American sea lion (Otaria byronia) will prey upon penguins in the Southern Atlantic when other food sources are scarce.

Penguin eggs and chicks on land are also vulnerable to hungry predators. In the Galapagos a major threat comes from an unsuspecting source; Sally lightfoot crabs (Grapsus grapsus) and Galapagos snakes (Philodryas biserialis) will steal eggs straight from the nest. In Australia the blue tongued lizards like King’s skink (Egernia kingie) and tiger snakes (Notechis scutatus) steal and eat little penguin eggs. Africa’s egg snatchers are mongooses (Herpestidae spp.) and sacred ibises (Threskiornis aethiopicus) and in Patagonia, Geoffrey’s cats (Felis geoffroyi) and gray foxes (Dusicyon griseus) often swipe eggs from penguins’ nests. In Antarctica the eggs and chick snatchers attack from above. Skuas (Catharacta spp) are notorious birds that cunningly attack nesting penguins in attempts to steal their young while sheathbills (Chionis spp) skirt around penguin colonies in search of abandoned eggs.

Human Impacts & Solutions

Despite their charismatic nature, penguin populations have been unable to avoid impacts brought about by humans. In addition to climate change that is severely impacting nesting and foraging grounds, penguins are also affected by oil spills, illegal fishing of prey, egg poaching, and the introduction of foreign predators like rats, dogs and cats.

Climate Change

For penguin species living in Antarctica, climbing temperatures due to climate change may be altering their living environment at a rate too fast for penguins to adapt. A study released in June 2016 predicts that by the end of the 21st century roughly 60 percent of Adélie penguin colonies in Antarctica will be decreasing in size because of changing climate. Another study predicts emperor penguin populations will also decline on average by about 19 percent during the same timeframe—with two thirds of the 45 known colonies experiencing declines greater than 50 percent. The colony featured in The March of the Penguins is one such colony. Experts warn at this rate the species could be headed for extinction.

Both Adélie and emperor penguins are ice dependent—the food they eat requires ice to grow and the ice floes provide protection and a resting spot during long foraging trips. When the ice declines, these penguins have trouble surviving, especially in winter. However, new information about juvenile nest fidelity reveals emperor penguins have a few tricks to help combat changing environments. A study in 2016 found that juvenile emperor penguins switch to breed in different colonies than the ones they were born into at a higher rate than previously thought. Though this will not completely prevent the eventual loss of the species in the face of melting ice, it does allow genetic diversity, a key component of evolution, to spread throughout the entire emperor penguin species. On the West Antarctic Peninsula, gentoo penguins (which do not rely on the ice) are better adapted to the warmer environment and their population numbers in Antarctica are currently on the rise.

If climate change alters ocean currents, as many models predict, the nutrient rich waters that currently support penguin colonies around the world may not provide enough food. Already, warming of the East Australian current off the coast of New Zealand is adversely affecting the little penguin. The African penguin is also struggling to find enough food to support its population. In 2024, the IUCN listed the African penguin as critically endangered. Across the globe, off the shores of Argentina, Magellanic penguins need to swim farther distances to find food, and chicks often drown as big storms with torrential downpours increase in frequency and strength.

Oil Spills

Oil spills pose a major threat for penguins living near congested shipping routes. Oil-slicked penguins, even when cleaned by restoration efforts, have significantly decreased abilities to reproduce. Roughly 10,000 penguins were either airlifted or transported via boat to cleaning facilities during the 1994 oil spill off of Dassen Island, South Africa. A 10-year study found that oiled penguins had an 11 percent decrease in reproductive success when compared to non-fouled birds of the same cohort. Another 26 percent became incapable of breeding.

Off Argentina, oil tankers once filled their empty oil tanks with seawater to help balance the ship when they were free of oil. Once in port the water was emptied into the ocean to make room for the petroleum, rinsing large amounts of oil along with it. It is estimated that 42,000 Magellanic penguins died annually in the 1980s from oily water. Changes in tanker routes to move them further offshore and a decrease in illegal wastewater dumping in 1997 have reduced penguin mortality rates.

Failures of the past also seem to be suggesting new ways of combatting the threats of oil spills when they occur. In 2000 nearly 90 percent of the penguins affected by the MV Treasure oil spill off the coast of Cape Town, South Africa were rescued. One of the most successful strategies was to round up 19,500 penguins in the path of the oil spill at Dassen Island and transport them roughly 500 miles away from home and the oil. The volunteer effort allowed the beaches to be cleaned while the rescued penguins made their way back home. These small successes are important considering the current population of African penguins is below 200,000, a startling number considering the 1.4 million that existed at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Illegal Fishing of Prey

Penguins rely on krill, anchovy, and sardines to survive but human fishing of these food web pillars has significantly impacted penguin population sizes.

Cape Town fishing of anchovies and sardines contributed to a 69 percent reduction in the African penguin population between 2001 and 2013. The sardine and anchovy fisheries, when combined, are the largest in South Africa, by volume and the second largest by revenue. A small sliver of hope comes in the form of no take zones, which in one case, off Robben Island, showed an 18 percent increase in African penguin chicks following a three-year fishing hiatus.

As krill fishing in the Southern Ocean increases due to the demand for Omega-3 oil used in supplements, scientists worry the removal could impact the higher trophic levels that include penguins, seals, and whales. The impact of the krill fishery is under close watch by scientists and the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), which was established in 1982 to regulate krill harvesting in the Southern Ocean.

The South Georgia Islands transformation offers another beacon of hope. Once a whaling community that decimated whale, seal and penguin populations, the island is now a haven for marine animals. The king penguin colony, once 350 pairs in 1912 has since rebounded to 60,000 pairs. The fishing regulations of the early 1990s ceased illegal fishing in the region and created sustainable krill and Patagonian toothfish (also known commercially as the Chilean Seabass) fisheries.

Egg Poaching and Guano Harvesting

Penguin populations are still on the rebound after the 19th century harvesting of eggs and guano, the poop of Humboldt penguins that was a valued fertilizer for farmers.

At the height of Peru’s exportation of bird guano (that included guano from other birds in addition to penguins) from 1840 to 1880 the country exported roughly two hundred million tons of guano valued at 2 million dollars. Today guano harvesting is regulated in Peru, including various marine protected areas along the coast that protect marine birds.

European explorers like Ernest Shackleton and Edward Wilson frequently ate penguin, a delicacy that remained on Antarctic menus until the 1950s according to a recipe book found at the British Antarctic Survey’s base, Rothera. In areas where penguins live close to humans, like the tip of South America, illegal egg poaching still occurs.

Foreign predators

Penguins thrived as flightless birds, in part because in the Southern Hemisphere there are few terrestrial predators like the foxes and badgers of the Northern Hemisphere. Human introduced animals, like dogs, cats and foxes are problems since the animals often eat penguin eggs, harass breeding pairs, or outright kill penguins.

In Australia the government supports strict enforcement when it comes to pets and penguins. In July 2016 a Tasmanian dog owner was prosecuted when his dog killed 18 penguins, and the National Wildlife and Parks Staff employ marksmen and other penguin protectors in areas where little penguins are frequently killed by the predators. One community on Middle Island trained a fleet of Maremma dogs, originally bred to guard goats and chickens, to protect the community’s penguins. The presence of the dogs has brought the once doomed population of four penguins to 200, a step towards restoring the population to its original 800.

In the Falkland Islands an unorthodox scenario protects many penguin colonies. A British territory, claimed because of its commercial worth during the 1800s whaling boom, the islands became the center of a disagreement between Great Britain and Argentina who claimed the islands their own. In 1982 the two countries went to war over the islands, and Argentina laid mines along their coasts. There are estimated to be roughly 20,000 landmines that remain along the coast, but the British deemed a removal endeavor too costly. The penguins that live on the islands are too light to set off the mines and the blocked off areas now serve as effective habitat conservation where the birds can breed undisturbed.

Research & Technology

Studying penguins that like to live in isolated areas and swim to great depths poses a problem for land-based scientists. This is why much of what we know about penguins comes from our observations on land where penguins breed. Fortunately, new technology is enabling researchers to have eyes where they cannot follow the flippered birds. Satellite tags and data loggers have been able to shed light on where penguins swim to in the winter. Scientists place small, battery-powered computers on the backs of penguins using waterproof tape or glue.

One technology that is significantly expanding our understanding of penguin behavior at sea is satellite and GPS tagging. Tags are attached to the back of the penguin and can record or transmit data as the penguin moves around on land and through water. Some tags can record temperature, depth and salinity measurements, relaying the information and location back to satellites that then relay the information to the scientist when the penguin surfaces. Other tags can log water temperature, body temperature, light levels, dive depth, date and time every few seconds over several years. The drawback is that penguins must be recaptured for the data to be downloaded, a tricky endeavor considering penguins travel long distances and can become prey to other animals.

Scientists have even discovered how to assess penguin populations without ever stepping on the Antarctic continent. The University of Minnesota Polar Geospatial Center uses high-resolution satellite imagery to scan the white Antarctic continent for a tell-tale sign of a penguin colony—their guano, or poop. Scientists can then count the number of penguins in the colony and even find new colonies unfound by manned expeditions on the ground. It was through satellite imagery that scientists discovered a massive "supercolony" of over 1,500,000 Adelie penguins, the largest colony of penguins on the Antarctic Peninsula. Other studies have also used a birds eye approach, but instead of satellites use unmanned aerial systems (UAS), also known as drones. As time moves forward comparisons of aerial and satellite images can monitor changes in the population sizes and distributions. Some scientists are using cameras and the power of citizen science to answer questions about the distribution of penguin species and their behavior. After a quick tutorial, visitors to penguinwatch.org can help scientists by marking adult penguins, chicks and eggs in still images from the Antarctic.

Cultural Connections

Movies, Comics, and Literature

The endearing and charismatic portrayal of penguins permeates through mainstream media—in books, movies, comic strips and video games.

Even the very first explorers of the Southern Ocean identified with the birds, attributing human-like qualities to those they encountered. The first description of penguins to a mass, general audience appeared in a Pall Mall Magazine article, written in 1895 by W.H. Bickerton. Bickerton was accompanying the crew of the Gratitude as they hunted penguins for oil, and upon his return, he wrote that the birds reminded him of “knots of men” and that they seemed like “a nation of people.”

Fast-forward to the twenty-first century, and we are still drawn in by their uncanny similarity to humans. The film March of the Penguins won an Oscar in 2006 for best documentary, and simultaneously the hearts of people around the world. It earned a gross $127,392,693 worldwide, second only to the documentary Fahrenheit 9/11.

In 1914 one of the first, popular, silent films called Home of the Blizzard, depicted penguins from the Antarctic as comedic entertainers. The New York Mail commented it was “Screamingly funny. The penguins are supreme comedians.” At the time vaudeville was at the height of its popularity and the portrayal of penguins in a similar style may have added to the success and visibility of the film. People often commented on the similarity between the iconic waddle of Charlie Chaplin and the waddle of the penguin, though Chaplin denied penguins were his influence.

The classic novel Mr. Popper’s Penguins written in 1938 continued the tradition of framing penguins in a comedic light, and by the 1960s dancing penguins debuted on the big screen next to Dick Van Dyke in Mary Poppins. But perhaps the most famous dancing penguins are the stars of the animated film Happy Feet (and Happy Feet Two). The 2006 blockbuster tells the story of Mumble, a young emperor penguin who is unable to communicate through song like all the other penguins but is a talented dancer instead. The filming process included an actor, dancer, and voice for each penguin character. Actors and dancers dressed in all black outfits with special motion reflectors that cued special cameras that digitized the movement. A penguin expert, Dr. Gary Miller, acted as a movement coach and advised the actors on how to move and behave like a penguin.

Not all penguin characters are amiable and cute. In Detective Comic number 58 the devious Oswald Chesterfield Cobblepot (a.k.a. the Penguin) appears as a pesky opponent of Batman. Inspired by “Willie the Kool” of Kool cigarettes, the Penguin dons a suit and top hat and walks with a hobble due to a hip impairment. The Penguin makes appearances in the 1960s Batman TV series and later, in the 1992 movie Batman Returns, Danny DeVito takes over the role and spins the character to be slightly darker and more sinister. In other stories, penguins fulfill more of a detective role. In the Doctor Who comic series a shape shifting character named Frobisher elects to assist the sixth and seventh doctors, abandoning his previous career as a private detective and assuming the shape of a penguin. The penguins in the popular Madagascar movies that came out in the 2000s were also slightly devious in their adventures.

The 1950s cartoon Chilly Willy follows the troubles of a penguin residing in Alaska (a misrepresentation considering penguins live in the Southern Hemisphere) as he attempts to keep warm in the snowy cold. It became fairly successful and was the second most popular cartoon produced by Universal Studios after Woody the Woodpecker.

Penguins as Icons

In the 1930s and 1940s, penguins became the stars of zoos around the world. Their popularity and iconic image prompted many companies to use their image in logos. In 1932 a British biscuit company created the P-P-P-Penguin bar and a year later “Willie the Kool” penguin made his debut as the mascot for Kool cigarettes. Penguin books released their logo in 1935, and it remains one of the most recognizable logos to this day (penguin or otherwise).

Additional Resources

Penguin Science - Current Research from Antarctica

Oceanites - Information about the Antarctic ecosystem

New England Aquarium Teacher Guide to Penguins

Criminal Penguins: A Penguin Nest Building Game

News Articles:

New Research Shows Penguins will Suffer in a Warming World (The Guardian)

Australia Used to be a Haven for Giant Penguins (Smithsonian.com)

Penguins Can’t Taste Fish, Says New Study (Huffington Post)

Books:

Fraser’s Penguins by Fen Montaigne

Penguins: Natural History and Conservation edited by Pablo Garcia Borboroglu and P. Dee Boersma

Sea Secrets: Tiny Clues to a Big Mystery by Mary M. Cerullo and Beth Simmons, illustrated by Kirsten Carlson (ages 5-10)

Documentaries:

March of the Penguins directed by Luc Jacquet (National Geographic)

Penguins: Spy in the Huddle (BBC)

Antarctic Edge: 70 Degrees South

The Penguin Counters