Great White Shark

Introduction

Sharks are much older than dinosaurs. Their ancestry dates back more than 400 million years, and they are one of evolution’s greatest success stories. These animals are uniquely adapted to their ocean environment with six highly refined senses of smell, hearing, touch, taste, sight, and even electromagnetism. As the top predators in the ocean, great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) face only one real threat to their survival: us. The assaults are many. By-catch: the accidental killing of sharks by fishermen's longlines and trawlers. Illegal poaching: selling shark fins for soup. Illegal hunting: sportfishing for shark jaws as trophies. Nets: placed along coastlines to keep sharks away from beaches. Pollution: toxins and heavy metals that build up in the shark's body. In some areas great white populations have plummeted by over 70%. If not stopped, it could lead to the extinction of this ancient species.

For more about all shark species go to our shark overview.

Life & Natural History

Intelligence & Anatomy

Brains over Brawn

Many scientists now believe that great white sharks are intelligent, highly inquisitive creatures. When great whites gather, they seem to show different behaviors, from open-mouthed gaping at one another to assertive body-slams. These sharks are top predators throughout the world's ocean, predominantly in temperate and subtropical waters. Great whites migrate long distances. Some make journeys from the Hawaiian Islands to California, and one shark that swam from South Africa to Australia made the longest recorded migration of any fish.

The torpedo shape of the great white is built for speed: up to 35 miles per hour (50 kilometers per hour). And then there are the teeth -- 300 total in up to seven rows.

But more than brawn, the great white shark has a tremendous brain that coordinates all the highly-developed senses of this efficient hunter. Its prey, including seals and dolphins, are very clever animals, and the shark has to have enough brains to outsmart them. Despite their reputation as lone hunters, great whites will cooperate with one another, hunting in groups and sharing the spoils. And some researchers have been surprised by how fast they learn.

Shark Senses

Great whites became the ocean’s top hunters through the evolution of supremely-adapted senses and physiology.

SMELL

Great white sharks' most acute sense is smell. If there were just a single drop of blood floating in 10 billion drops of water, they could smell it! Their nostrils are on the underside of the snout and lead to an organ called the olfactory bulb. The great white’s olfactory bulb is reported to be the largest of any shark.

HEARING

Shark external ears are hard to see: they are just two small openings behind and above the eyes. The ears may be small, but they’re powerful. Inside, there are cells that can sense even the tiniest vibration in the surrounding water. Sharks also have an ‘ear stone’ that responds to gravity, giving the animal clues as to where it is in the water: head up, head down, right side up, or upside down.

VISION

A great white sharks has great vision. The retina of its eye is divided into two areas – one adapted for day vision, the other for low-light and night. To protect itself, the great white shark can roll its eye backward into the socket when threatened.

ELECTRO-RECEPTION

Sharks have a sense that humans can only be in awe of – they can sense an electrical field. A series of pores on the shark’s snout are filled with cells called the Ampullae of Lorenzini that can feel the power and direction of electrical currents. Scientists have discovered that sharks can use this sense to navigate through the open ocean by following an electrical ‘map’ of the magnetic fields that crisscross the Earth’s crust.

TASTE

Great white sharks are opportunistic eaters. Depending on the season, area and age, they will hunt seals and sea lions, fish, squid, and even other sharks. They have taste buds inside their mouths and throats that enable them to identify the food before swallowing.

TOUCH

Great white sharks have an elaborate sense of touch through what’s called the lateral line – a line that extends along the middle of the shark’s body from its tail to its head. This line, which is found in all fish, is made of cells that can perceive vibrations in the water. Sharks can detect both the direction and amount of movement made by prey, even from as far as 820 feet (250 meters) away.

Diversity

Sharks come in all shapes and sizes. Today there are more than 440 known species -- from the 6-inch long dwarf lantern shark (Etmopterus perryi) to the 60-foot long whale shark (Rhincodon typus).

Unlike typical fish, sharks do not produce large amounts of small eggs. Instead, they invest their resources in fewer, larger eggs which are more likely to grow into adults. Some sharks lay eggs, while others give live birth. Great white sharks gestate their pups for a year before giving birth – that’s longer than humans. Between 2 to 12 babies are born at a time.

Great whites can live up to 60 years, maybe more. Most sharks are slow to grow and take a long time to mature. That means that on the whole, sharks reproduce only a few young, making them all the more vulnerable to extinction.

Evolution

Shark Ancestors

We may think that great whites are massive, but their ancestors would likely have made them appear midgets by comparison. An ancient shark called the Megalodon (Carcharodon megalodon), appeared on Earth more than 20 million years ago. Based on fossil teeth, scientists believe these sharks could have been as big as a school bus—big enough to probably feast on whales.

For a long time, scientists thought the Megalodon was the direct ancestor of great white sharks. But new fossil evidence, announced in November 2012, suggest that it was more closely related to an ancestor of mako sharks—smaller but faster fish-eating sharks.

Another shark ancestor swam the ocean 290 million years before today. Picture a shark with a teeth shaped in a ring like a saw. This fossil comes from the long-extinct Helicoprion, a buzzsaw with fins. But what did this animal actually look like? All scientists had to go on was a few fossil specimens and came up with a litany of possibilities, some more plausible than others.

The face of Helicoprion was finally uncovered when a well-preserved fossil was brought in for a CT scan, and the result was published in 2013. Most of the toothy spiral is buried in the fish's lower jaw, with just a few teeth emerging. Using the new evidence, the reconstruction is the most accurate to date—and proves some earlier reconstructions wrong. The study also found that Helicoprion is not the ancestor of a great white shark but, rather, to the chimaeras, a group of deep sea shark relatives.

Shark Relatives

Just look at these x-rays. Not a single bone. Instead, these are animals with skeletons made from cartilage. These boneless fishes are in a class called Chondrichthyes that includes sharks, skates and rays. Sharks are also distantly related to the mysterious and rare chimaeras, which are found in deep ocean waters. Their enigmatic behavior has earned them names like spookfish or ratfish.

Science

Scientist - Alison Kock

Marine biologist Alison Kock has devoted her life to finding the facts and defusing the myths about great white sharks. "My dad and I used to go on regular diving expeditions together, which fostered a love for ocean creatures, especially sharks. I will never forget the first time I saw a white shark flying clean out of the water and into the air while chasing a seal. From that day onwards, I have spent thousands of hours at sea studying these vulnerable creatures and have been fortunate to get to know that the real white shark is not a mindless killer. They are complex and majestic animals that are completely misunderstood."

Research

DNA Identification

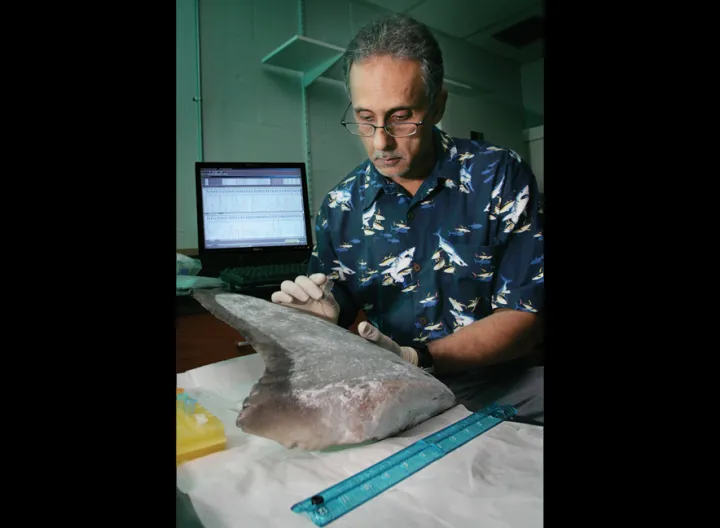

DNA is a key tool in criminal cases. And that’s not just true of crimes against people. It’s true of crimes against sharks. It’s illegal to hunt great white sharks in South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Malta, Namibia, Israel and the United States and DNA testing by scientists like Mahmood Shivji can prove when a fisherman has broken the law. Watch Dr. Shivji talk more about using DNA from shark fins to determine what species of shark are being killed, often for use in shark fin soup.

Collections

Shark Teeth at the NMNH

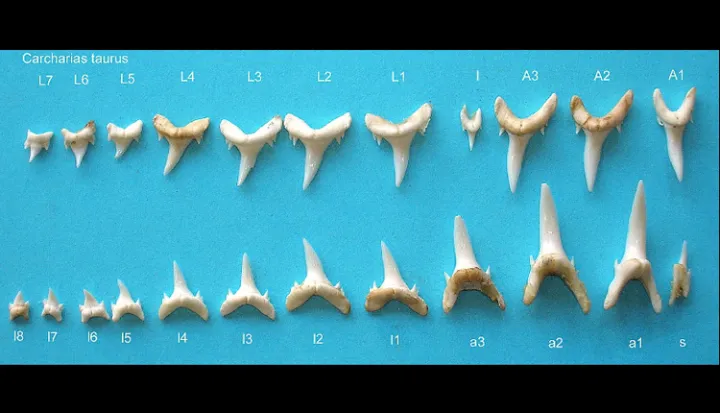

The Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History has one of the largest collections of fossil shark teeth in the world – more than 90,000 different teeth. The oldest date back about 360 million years to the Devonian Period. Shark teeth come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes (pdf), all depending on their purpose. Flat teeth are adapted for crushing and grinding. Sharp and pointy teeth make it easier to grasp and hold slippery prey. Serrated teeth are ideal for ripping and tearing prey too large to swallow in one bite.

Human Connections

Great white sharks have many more reasons to fear people than people have to fear them. Thousands of sharks are killed every year especially for shark fin soup.

Conservation

Why We Should Save Sharks

Fear of sharks seems to be encoded in our genes. Yet humans are rarely attacked by a shark, while millions of sharks are killed by humans. Some populations of shark species, such as the shortspine spurdog, may have dropped by 95 percent. The sharks’ population decline has a ripple effect – throwing entire marine ecosystems out of balance. Shark species often are especially vulnerable to overfishing because of specific life characteristics, such as not mating until later in life, and giving birth to small litters of live young. Sharks even have allies from a group of people who you would least expect - shark attack survivors are banding together in order to urge people to protect sharks.

Why save sharks? The reasons are many. Sharks keep the ocean healthy because they keep different prey species from becoming overabundant. Sharks keep the ocean clean by scavenging on dead animals. Sharks keep other species more fit by weeding out sick and weaker individuals. And sharks are beautiful – like lions and gorillas – crowning achievements of evolution.

Cultural Connections

Shark Fin Soup

Shark fin soup is considered a delicacy in many Asian countries, once reserved only for the wealthy or for very special occasions. But rising incomes in Asia are having a disastrous impact on sharks. To make the soup, the fins of the sharks are sliced off and the rest of the body is tossed back in the water, dead or alive: a method called shark finning. It's estimated that 100 million sharks are killed annually to supply fins for soup. Fins from great whites can fetch the highest prices because of their rarity and size. In Hong Kong, Taiwan and China, conservationists and chefs are leading campaigns to stop serving shark fin soup. (Read more about shark finning and its effects.)

Threats and Solutions

Shark Nets

Dozens of shark nets have been installed off the east coast of South Africa and Australia. These nets are meant to protect swimmers from rare attacks. The nets entangle, suffocate and kill sharks as well as indiscriminately kill other animals -- like rays, turtles, dolphins and whales.

Shark Sanctuary

Great white sharks are a global species – and saving them will take a global effort. Some steps have already been taken. Countries like South Africa, Namibia, Australia, New Zealand, Israel, and Malta have fully protected great white sharks in their national waters. In California, NOAA is protecting the sharks that feed in the Gulf of Farallones National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of California. And the international organization CITES has implemented a ban on all international trade of products that come from great white sharks.