The Megalodon

Introduction

Carcharocles megalodon was once the most fearsome predator to reign the seas. This ancient shark lived roughly 23 to 3.6 million years ago in nearly every corner of the ocean. Roughly up to 3 times the length of a modern-day great white shark, it is the largest shark to have ever lived. It had a powerful bite with a jaw full of teeth as large as an adult human’s hand. They likely could tear chunks of flesh from even the largest whales of the time. It should come as no surprise that upon discovery in the fossil record, the massive shark was named Carcharocles megalodon or “big toothed glorious shark.”

Now well-known within pop culture, Carcharocles megalodon is known by many as simply the megalodon, though it is important to note this shortened version is also the name of a genus of clams and can be cause for confusion within the scientific community. For the following text, Carcharocles megalodon will be shortened to the megalodon, a reference to the shark and not the clam.

Are You An Educator?

Anatomy, Diversity & Evolution

Anatomy

A Big Shark

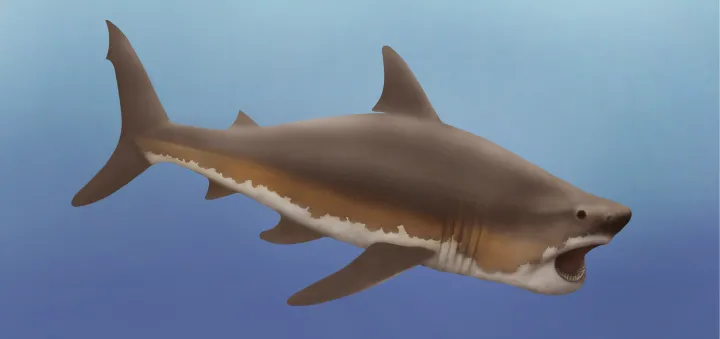

The megalodon is the largest shark to have ever lived in the world’s ocean. Like other sharks, they had streamlined yet powerful bodies built to efficiently cut through the water. Their tailfin undulated side to side and they breathed through gill slits on either side of their head.

Like other elasmobranchs (a group of fishes that includes sharks, rays, and skates), megalodons have skeletons mostly made of cartilage—the hard but flexible material that is found in human noses and ears. This is a defining feature of elasmobranchs, as most fish have skeletons made of bone. Much lighter than bone, cartilage allows sharks to stay afloat and swim long distances while using less energy. It is also very difficult for cartilage to fossilize, so much of what we know about megalodons comes from their teeth, vertebrae (which contain calcium and therefore are preserved), and fossilized poop. The proposed shape of a megalodon is therefore based on the anatomy of living sharks. Modern research shows that the megalodon is most closely related to mako sharks, not to the Great White.

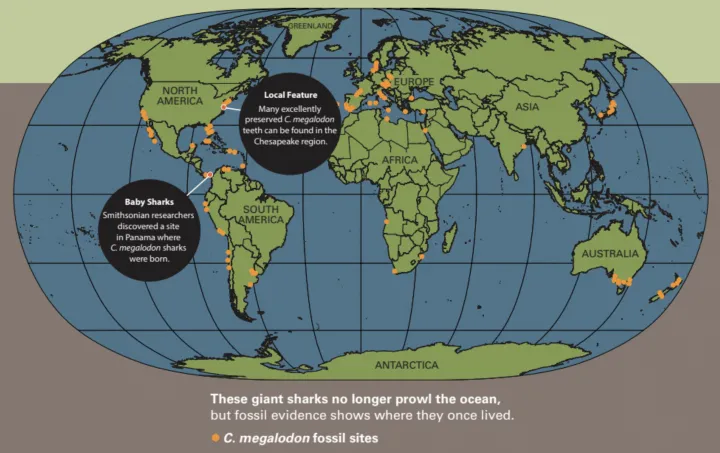

Every shark, including the megalodon, has several rows of teeth lining its jaw. Unlike people, who have a limited number of teeth in their lifetime, sharks constantly shed their teeth and replace them with new ones. A shark can lose and replace thousands of teeth in its lifetime. Megalodon teeth are no different, and their teeth can be found scattered on coastal beaches or just offshore. They are especially large—some reach over 7 inches (18 cm) in vertical height.

Size & Strength

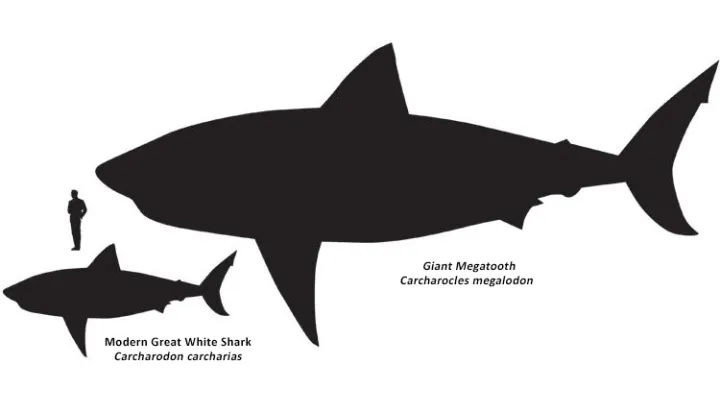

The megalodon was a massive shark. The largest were roughly 60 feet in length and attained perhaps up to 50 tons, the size and weight of a railroad car. Female megalodons were, on average larger, at about 44 to 56 feet (13-17 m) and males were about 34 to 47 feet (10-14 m). Due to the lack of cartilage fossils, megalodon size estimates are based upon known relationships between tooth size and shark body length.

Diversity & Evolution

Sharks first appear in the fossil record roughly 420 million years ago, a time when fishes began to evolve. The ocean was a very different landscape, with most creatures lacking a backbone. Trilobites, creatures distantly related to spiders and horseshoe crabs, scurried across the seafloor while shelled cephalopods, relatives of squid and octopus, reigned as the top predators above in the water column. By the Carboniferous and Permian periods, sharks of all kinds roamed the world’s seas. The lineage leading to the megalodon first appeared about 60 million years ago. Even the earliest member of this lineage was already longer than a great white shark.

The megalodon is a member of the lineage of lamnoid sharks (Lamniformes), which also include the great white, mako and thresher sharks, among others. This lineage can be traced back to the Cretaceous Period.

For a long time, scientists believed the megalodon’s closest relative was the great white shark. In fact, the two species likely even lived at the same time. Modern scientific studies have shown that megalodon was more closely related to an ancestor of mako sharks—smaller but faster fish-eating sharks.

Ecology & Behavior

Distribution

The megalodon lived in most regions of the ocean (except near the poles). While juveniles kept to the shores, adults preferred coastal areas but could move into the open ocean. The most northern fossils are found off the coast of Denmark and the most southern in New Zealand.

In the Food Web

The megalodon was a fearsome predator. As the largest predator of the time, it ate a diverse array of prey including toothed and baleen whales, seals, sea cows, and sea turtles. As an opportunist, it also likely ate fish and other sharks. Many whale fossils have distinct gashes from megalodon teeth, and sometimes an entire megalodon tooth is found embedded in a whale bone. Scientists calculate that a bite from a megalodon jaw could generate force of up to 40,000 pounds, which would make it the strongest bite in the entire animal kingdom.

It is through these tooth marks that scientists are able to determine a megalodon’s feeding behavior. It is believed that larger prey, like small whales, were struck in the chest, the robust megalodon teeth able to puncture through their tough ribs. Conversely, they likely rammed smaller prey with their snouts to stun them before biting it.

Reproduction

Like the modern-day bull shark, megalodons gave birth in specific nursery habitats that included protected bays and estuaries. These locations provided the shark pups with plenty of fish and a safe environment to grow, away from the larger predators of the open ocean and offshore zones. Scientists have discovered megalodon nursery habitats in Panama, Maryland, the Canary Islands, and Florida.

Extinction

With such a large body size, the megalodon required ample prey to fuel its body. Around 2.6 million years ago, around the time when the megalodon disappears from the fossil record, large mammals in the ocean were undergoing significant changes in response to a changing climate. At the beginning of the Miocene, marine mammals were at the height of their diversity and abundance—especially the megalodon’s favorite prey, small whales. But later during the Pliocene, there was a drop in ocean temperatures that likely contributed to the megalodon’s demise.

For much of the Cenozoic Era, a seaway existed between the Pacific and Caribbean that allowed for water and species to move between the two ocean basins. Pacific waters, filled with nutrients, easily flowed into the Atlantic and helped sustain high levels of diversity. That all changed when the Pacific tectonic plate butted up against the Caribbean and South American plates during the Pliocene, and the Isthmus of Panama began to take shape. This tectonic collision caused volcanic activity and the formation of mountains that stretched from North to South America. As the Caribbean was cut off from the Pacific, the Atlantic Ocean became saltier, and the Gulf Stream strengthened and propelled warm water from the Equator up into the north. Today, the salty water of the Atlantic is a major engine for global ocean circulation. Ecosystems, too, reacted to the closure of the seaway. Cordoned off from the nutrient-rich waters of the Pacific, Caribbean species needed to adapt. The barrier led to the creation of pairs of related species, such as the Pacific goliath grouper and the Atlantic goliath grouper, but other species didn’t fare so well. It is likely that the giant megalodon was unable to sustain its massive body size due to these changes and the loss of prey, and eventually went extinct.

At the Smithsonian

On Display

In the Sant Ocean Hall, a gaping megalodon jaw filled with teeth is a favorite place for museum-goers to snap a group photo or selfie. To show its teeth the mouth has been opened wide. In the living shark, the jaws could not be opened to that extent.

Take a trip to the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. and you will come face to face with a life-size replica of a the megalodon. At 52 feet, the model is the average size of a female megalodon. In order to show the large teeth, the model is displayed with its mouth open. The megalodon was a new addition to the West courtyard of the museum in Spring 2019.