Six Ways to See Ocean Ocean Bioluminescence

Whether it’s the winter dance of the Northern Lights or the summertime glow of fireflies, displays of natural light fascinate us humans. Bioluminescence is the source of many such light shows in the wild—especially in the ocean.

Similar to when you crack a glow stick and shake it up, numerous marine animals, plants, and microbes emit bioluminescent light through a chemical reaction. While the light is beautiful, the goal isn’t aesthetic; rather, bioluminescence helps the organism that produces it evade predators, feed or reproduce.

Seen in person, bioluminescence is breathtaking. Here are some ways you can catch sight of life lighting up the ocean:

Glittering Waves

Bioluminescence is readily visible in scores of microscopic marine organisms, including many of the thousands of dinoflagellate species found throughout the world’s oceans. A slight movement can trigger the bioluminescence in these tiny one-celled plankton, making for spectacular shows as they light up a wave crashing onto the shore or the wake of a boat speeding through the dark.

Why the small creatures light up is still not entirely clear. Bioluminescence can serve a variety of purposes, such as signaling predators to stay away or beckoning mates to come closer. The light can also serve as a tool for those too tiny to defend themselves: When they light up, the microorganisms attract attention in what marine biologist Edith Widder calls a “bioluminescent burglar alarm”. Scientists believe that dinoflagellates may be hoping the fierce glow will scare off predators or attract bigger predators that will eat their pursuers.

The bioluminescence of one species in particular, Lingulodinium polyedrum—known for causing red tides and lighting up the Southern California coast—has its own circadian rhythm, producing more reactions at night than during the day. The chemicals and proteins within L. polyedrum are destroyed on a daily basis and regenerated for their nighttime light show—like the one seen here in a long-exposure photograph. Red tides are unpredictable, though, so if you’re hoping to catch a glimpse of the sparkling scene in the wild, you might want to book a trip to Mosquito Bay, off the island of Vieques in Puerto Rico. The glowing waters can be traversed by kayak in the dark, and although in recent years the bioluminescence there has dimmed, it is still a sight worth seeing.

Seductive Beacon

Travel to Bermuda’s waters and you’ll see the ocean’s version of online dating, starring the bioluminescent Bermuda fireworm. Several nights after the full moon, female fireworms swim up from the soft bottom of the seafloor to the ocean’s surface. There they swim in circles while alight in a bioluminescent call to male fireworms—like posting your best selfie and waiting for the date requests to roll in.

The males that heed that call swim up toward the circling females and flash in response, creating a scene like a wild nighttime dance party. Lit by the waning moon and each other, males and females simultaneously release their eggs and sperm into the water.

Sharing the Love

Some animals could benefit from a little light beneath the waves but don’t have the necessary proteins to produce a bioluminescent reaction themselves. In these cases, bacteria may come to the rescue. Within hours of birth, the Hawaiian bobtail squid attracts bioluminescent bacteria, which colonize a special light organ above its eyes. The bacteria and squid are able to live independently, but they both benefit from this relationship: The bacterial light helps the squid avoid predation, and the bacteria gain a safe home and consistent nutrients. These tiny squid, like the one seen above, can be found in very shallow water around the Hawaiian and Midway Islands, so all you need is a mask and snorkel to find them.

Similar symbiotic relationships exist between bioluminescent bacteria and a variety of other animals. The flashlight fish harbors glowing bacteria directly beneath its eyes and can turn its “flashlights” off and on at will with specialized lids. In some places these fish are in shallow enough waters to be found without using SCUBA. The brightly lit lures of large female anglerfish also harbor bioluminescent bacteria to attract hard-to-find food in the deep sea. And pinecone fish (sometimes called pineapple fish) attract food with a microbe-infused glowing bottom lip, which they can tuck into their mouth to turn off the light.

In another form of partnership, glowing bacteria may help deep-sea animals find their next meal. The microbes often colonize dead animals after they fall to the seafloor, possibly helping scavengers see in the dark. In some places you can even see bioluminescent bacteria glowing on their own. The milky seas they cause can be seen from a boat if your timing is right—and is sometimes visible from space!

Fireflies of the Sea

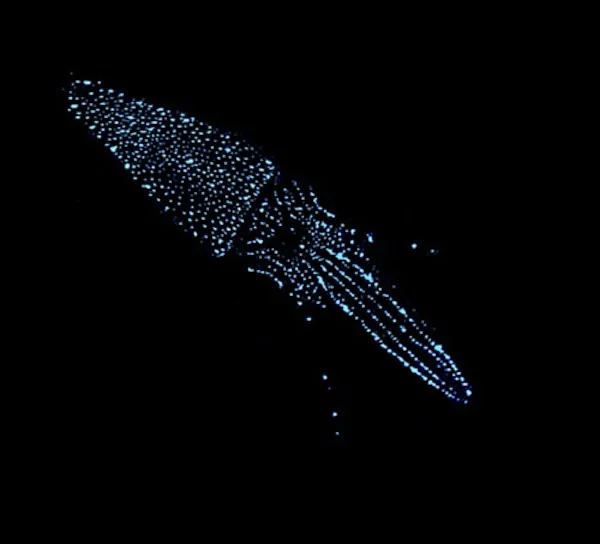

Not to be outdone by their insect counterparts on land, firefly squid are known for their bright blue light shows off the coast of Japan. The small squid fill up Toyama Bay during their spawning season from March to May. Waves push the squid closer to the surface in the enclosed waters of Toyama Bay, making it an ideal time for marine mammals, larger fish and humans—both observers and fishers—to take advantage of the spectacle.

Lined with light-producing organs called photophores, the squid are thought to use their light for many forms of communication—from attracting mates to deterring predators. The photophores can light up in unison and also in an alternating pattern. Tour boats embark in the middle of the night and allow visitors to watch the light show as nets from fishing boats prod the squid to light up. There is even a Firefly Squid Museum if you happen to visit during the off-season.

In the Caribbean, tiny crustaceans called ostracods also play firefly when they are looking for mates, according to science writer Jennifer Frazer, who saw them in the waters of Bonaire. Ostracods not only light themselves up, they also release glowing mucus into the water. The specific spacing of the mucus blobs tells female ostracods that a male of their species is close by and ready to mate.

A Coastal Light Show

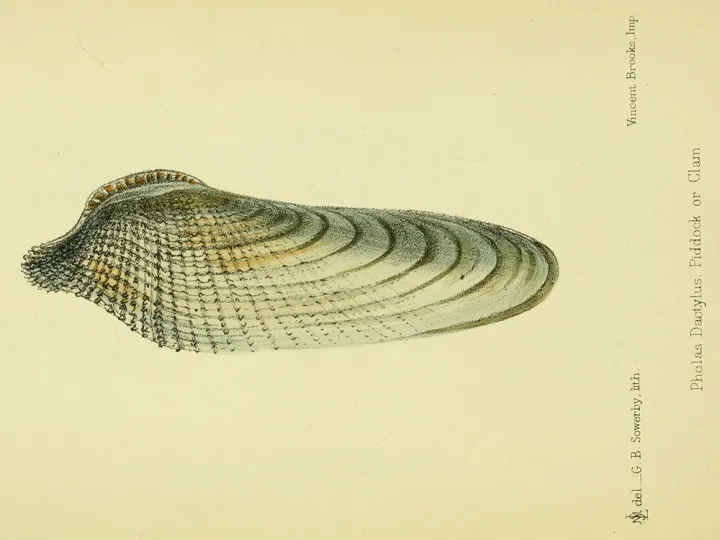

If you’d like to stick to land to see ocean creatures light up, the rocky shores of England and France are home to the bioluminescent clam Pholas dactylus, seen above next to a bore hole. These small clams bore into rocks on the shores of the Atlantic and Mediterranean. From their encased homes, they emit bioluminescent light through their mucus and along their bodies, lighting up parts of the coast for those who take an evening stroll.

These clams have been noticed throughout history. Pliny the Elder wrote about how they light up the mouths of those eating them. More importantly, they were central to the discovery of the proteins luciferase and luciferin. French pharmacologist Raphael Dubois extracted these proteins, essential to the internal production of luminescence, from Pholas dactylus in the 1880s. Today the proteins are valuable biological research tools used, for instance, in genetic studies and live-animal imaging.

A Glimpse of the Deep

Most bioluminescent organisms are found in the deep sea, where researchers estimate that more than 50 percent of organisms glow from the special chemical reaction. As terrestrial travelers are unable to withstand the pressure at depth, we miss out on most of the ocean’s light show. But we know from remote exploration that light-producing photophores are found along the belly and tail of the lantern fish, on the belly of hatchetfish (seen above) and behind and under the eyes of dragonfish, among many other deep-sea fish known to science.

On the island of Sicily, you can see some of these deep-sea wonders at the local fish markets. The narrow Strait of Messina separates Sicily from mainland Italy, and just 30 miles from its shallow waters are trenches reaching depths of 6,000 feet. In this unique spot, currents and waves carry creatures from the deep sea to the surface, where they are caught and sold. Mid-level fish, such as the hatchetfish and lantern fish, move up to the surface at night where their photophores can be observed and fishers can make their catch.

If you get the rare opportunity to see deep-sea lights in a submersible, jump on it. Those who have had the chance through scientific endeavors or thanks to saved pennies say it is most certainly worth it. In this short video, scientists describe the experience: “You’re looking out the window and all you see are these stars that go by, which are the bioluminescent organisms,” says one. “You’re starting to see sparks; it’s like the sparks that come off a campfire,” says another.

Editor's note: this article was originally published on June 9, 2015, at SmithsonianMag.com.