Winter Under the Waves

On land, changing seasons are unmistakable—leaves change, fall, and bare branches are soon covered in a dusting of snow. Animals, once abundant and scurrying about hunker down in dens or muddy pond floors. Though the ocean climate may be buffered from more dramatic temperature swings, ocean dwellers react to the season’s change too. Here is a list of some strategies plants and animals use for weathering the winter months in the ocean.

In the Air

As the seasons change, birds take flight. The warm summer months in temperate regions turn cool, meaning less food for hungry bellies. Petrels, penguins, albatross, piping plovers, and other ocean species often travel thousands of miles to warmer climates, where they overwinter and feed. The most remarkable migration, however, is that of the Arctic tern, which averages over 43,000 miles (70,000 km)—across the entire globe. The Arctic tern effectively skips winter, spending the months of April to August in the polar regions of the Northern Hemisphere and then flying all the way to Antarctica to catch the Southern Hemisphere’s summer months.

Across the Sea

Whales, sharks, sea turtles, and seals are some of the largest animals in the ocean, and when winter comes knocking on the door, they have the mass and power to move across the globe chasing food, warmth, or both. Elephant seals are one such animal. Though often thought of as coastal dwellers, elephant seals are extreme swimmers that can cross entire ocean basins. From the summer breeding grounds of California and Mexico, northern elephant seals travel to the Aleutian Islands of Alaska where they feed in the productive Arctic waters. During their travels, the seals spend between 80 and 95 percent of their time underwater, only popping up to the surface for a quick breath before diving back down.

A Winter Mud Bath

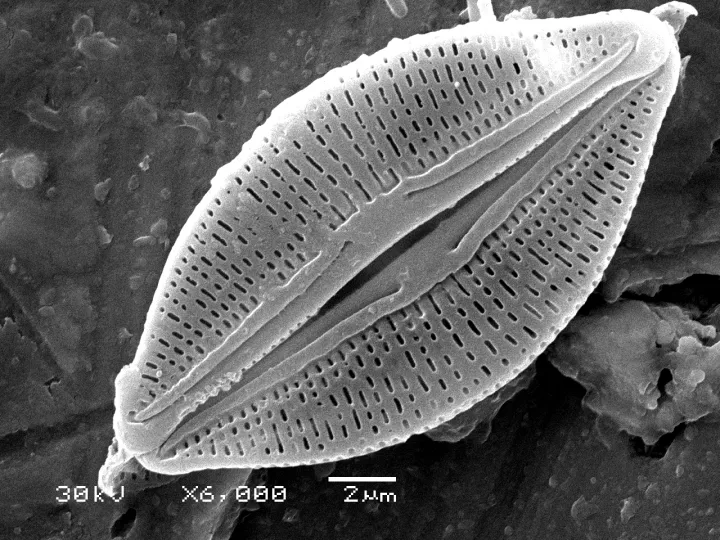

Sunlight is the key to a phytoplankton’s survival. Photosynthetic algae, they convert the sun’s rays into the energy that keeps their body fueled and running. So, what happens at the poles when winter turns the world dark? Diatoms, a type of phytoplankton, go dormant. After the summer’s bloom, diatoms shrink in size and begin to thicken their outer glass skeletons. The transformation turns them from light and buoyant to dense balls and they sink to the seafloor. There, they stay immersed in the muddy bottom all winter, riding out the dark months safely snuggled away from predators. As the seasons warm, the water currents shift and flush the diatoms back to the surface where the sun is once again shining.

Up and Down Rivers

For some fish, life at sea is only temporary. After a summer of feeding offshore, some species of fish swim up rivers to spawn or overwinter in freshwater habitats. Ever heard of the salmon run? This is one such migration. Salmon spend the majority of their lives living in the ocean and then in their final year during the autumn and early winter months they swim upriver to spawn and then die. Steelhead trout, a relative of salmon, also migrate from the ocean to rivers in the winter, but they do this on an annual basis, coming back year after year to the stream where they were born.

European and American eels split their time between rivers and the ocean too, except they feed in rivers and come to the ocean to spawn. In October, mature eels make their way down rivers and into the ocean where they then make the long trek to the Sargasso Sea. By January, mating ensues, a mysterious event that scientists have yet to observe. Once they’ve mated, mature eels die.

Deeper Down

While on land, animals must either turn to the sky or travel across the Earth to escape the winter season. In the ocean there is one other option—to go down. Caribbean spiny lobster travel to deeper waters when the shallow waters begin to cool in the winter months. Frequent autumn storms bring about turbulent seas that are treacherous for lobsters. They also cause sudden dips in the temperature, sometimes as dramatic as 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) at once. When it’s time to leave, lobsters align themselves with the Earth’s magnetic field, sometimes forming single-file lines that include over 50 lobsters. Forming a line reduces drag which is especially helpful since their migrations can be over 30 miles (50 km) long.

Going Dormant

For many fish species, winter is a time to take it slow. Fish will often decrease their activity level, growth, and feeding behavior in response to colder temperatures as a way to survive the colder and leaner months. Warm up the water and they come back to life. One fish takes it a step farther—the Antarctic spiny plunderfish goes into hibernation during the winter months even though the ocean temperature barely changes. Scientists believe this is in response to the loss of the sun and the resulting decrease in phytoplankton, just as bears hunker down when berries and nuts become scarce. It is the only instance of true hibernation in fish.