CARTHE Drifters: Where does oil go when it is spilled?

Throw a message in a bottle into the vast ocean and where does it go? The answer to this question is not just a romantic curiosity. Thinking about where a small floating item might end up in the immense ocean can help us understand the currents and movements of the water, which has many important uses, including helping us respond better to oil spills.

Oil spills can have disastrous impacts on coastal ocean ecosystems, human health, and the economy, as seen in the Gulf of Mexico Deepwater Horizon spill in 2010. However, scientists still don’t know exactly where oil goes and how quickly it moves when it spills in the open ocean. The global process of water movement, often known as the “global ocean conveyer belt,” is much better understood than the small, local movements that occur on a daily, weekly, and even monthly scale. These movements are influenced by wind, waves, upwelling (water rising from the seafloor to the surface), and other factors that are difficult to predict precisely.

Scientists are now able to track surface ocean currents with a higher degree of accuracy with the help of floating “drifters" released into the ocean waves. These drifters are each like a message in a bottle, recording information on their locations that is sent back to researchers on land (or in a boat). They are used by the CARTHE project—which stands for the Consortium for Advanced Research on Transport of Hydrocarbon in the Environment—to learn more about the movement of the ocean.

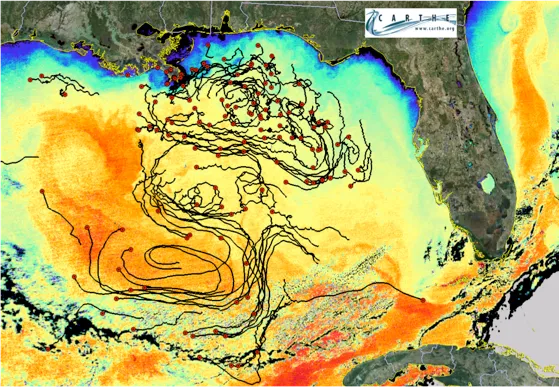

Releasing hundreds of floating drifters on the ocean surface refines the complex story of ocean movement told by a dozen or so computer models running thousands of iterations. The drifters bob in the waves, constantly recording data that can be incorporated into models to confirm (or deny) the accuracy of their predictions. In 2012, a CARTHE project called the Grand LAgrangian Deployment (GLAD) released over 300 one-meter-tall plastic drifters into the Gulf. As the waves scattered them, they sent 5.7 million data points about their positions back to the researchers, information collected every five minutes by GPS satellite. The biggest experiment of its kind, the key to the drifters' success was the large number of drifters, which allowed them to receive bits of information from many slightly different locations within the same ocean area at the same time.

Drifters themselves can be various shapes and sizes. After the GLAD experiment, researchers realized that a smaller, less clunky, and less expensive drifter would be necessary for an even larger deployment. They also wanted to reduce the harm done to wildlife, so they developed new drifters from a material that would eventually biodegrade rather than slowly break into thousands of plastic pieces if left at sea. In 2013, thirty of these new biodegradable drifters, along with over 200 additional scaled-down drifters, were released close to shore in order to understand why oil bumping up against the coast might move and collect in one inlet but not another. As coastal waters move very quickly, these were captured and redeployed several times throughout the three-week experiment.

The CARTHE team also released pink dye during this experiment to learn more about how seawater moves below the surface of the water. Tracked by a motley crew of pre-placed underwater sensors, two small drones, a helicopter and a kite, the dye helped to fill in gaps in our understanding of the ocean’s movement from below the surface. Even with these experiments, however, the entire story of below-surface currents is hard to follow. The deep sea isn’t as well suited to drifters and dye because drifters are harder to track and dye can’t be seen. There also is less directional movement the deeper you travel from the ocean’s surface. In the deep sea, clumps of oil break down into droplets and enter the deep sea ecosystem—getting gobbled up by animals, sticking in marine snow clumps, or falling to the seafloor to be eaten by microbes.

Armed with these new, real-time data about surface and below-surface currents, CARTHE scientists are refining ocean models and thinking ahead to the future. Not only can these new data help improve models of ocean currents that can be used for future oil spills or other pollution events, but they also capture information that can be helpful in understanding weather patterns, algae blooms, and with search and rescue missions. Accurate models can even play a role in reduction of carbon emissions—helping ships to reduce fuel needs and teaching us more about possible wind and wave energy production. Now that this type of research can provide huge amounts of data and is not exorbitantly expensive, the next step is to distribute drifters in larger areas, at different times of year, and in different parts of the ocean. In this way, drifters can continue to help us understand where the ocean may take a message in a bottle—one data point at a time.

The Ocean Portal receives support from the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) to develop and share stories about GoMRI and oil spill science.

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. For more information, visit http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.