Underwater Robots Explore the Ocean

Glider Technology Now Used to Study Oil Spill in Gulf of Mexico

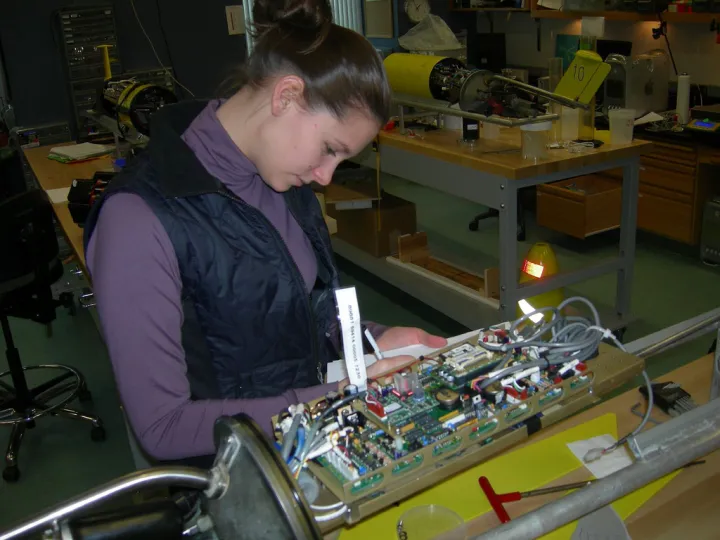

The first underwater robotic vehicle—or “glider”—to cross an ocean is the centerpiece of a new temporary exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. The U.S. Integrated Ocean Observing System, through Rutgers University, carried out the trans-Atlantic journey in 2009, just months before the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico became the first U.S. oil spill where glider technology was applied.

The Scarlet Knight (also known as RU27) is an 8-foot autonomous underwater glider that traveled from New Jersey to Spain, tracing the 517-year-old path of Columbus’s ship, the Pinta. Its underwater expedition, spearheaded by undergraduate students from Rutgers University, has provided data to help scientists better understand how climate change is affecting the ocean.

“We are very pleased to showcase this milestone in ocean research and exploration here in the Sant Ocean Hall,” said Eva Pell, Smithsonian’s Under Secretary for Science. “The story of the glider and the undergraduate students who monitored its journey shines light on the mysteries of the oceans; it speaks to the importance of technological creativity to mine those secrets, and to education as a vehicle to achieve the goal of understanding the greatest resource of our planet."

Glider Crosses the Atlantic

The glider, with no engine to propel it forward, rode the ocean currents and made a series of 10,000 dives and ascents in order to collect data on ocean circulation, the heat content of the upper layer of the ocean, and the transport of this heat through oceanic circulation as it crossed the Atlantic.

Descents involved pumping a small volume of water into its nose causing it to sink and unequal buoyancy along the fuselage would send the glider 150 to 180 meters down the water column. Ascending involved the reverse: pumping approximately a cup of water into the tail causing a glide upwards. This pattern of dive-and-ascend cycles continued for 4,600 miles; they lasted approximately 40 minutes each. The glider stayed almost continually underwater, surfacing only three times a day to check its location, transmit data, and download new piloting instructions from home via an Iridium telephone on its tail.

Fishing nets and wildlife posed dangers, but through continued collaboration with fishermen during the glider’s first hazardous week, the Scarlet Knight achieved all mission objectives.

The glider was dubbed Scarlet Knight in honor of the Rutger’s mascot. The Rutgers team and their Spanish colleagues from Puertos Del Estado (the Spanish Port Authority) recovered the glider off the Spanish coast after seven months at sea, and brought it ashore in the small town of Baiona where Christopher Columbus’s ship, the Pinta, landed with news of the New World more than 500 years ago. The glider reached Baiona on Dec. 9, 2009—one year to the day of the exhibit being launched within the Smithsonian’s Sant Ocean Hall.

Fleet of Gliders Sent to Gulf of Mexico

“Gliders sample the ocean in places it is impractical to send people and at a fraction of the price,” said Zdenka Willis, director of the U.S. IOOS Program. “Using robots to collect scientific data is the wave of the future in terms of ocean observing.”

As part of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill response effort, IOOS partners deployed a fleet of gliders equipped with sensors to help indicate the presence of oil. Though scientists must still confirm oil presence through water sampling, gliders narrowed the search zone for subsurface oil.

“New technologies give us greater insight into how the ocean works. The trans-Atlantic glider, in particular, helped reduce uncertainty in some of our climate models,” said Richard L. McCormick Rutgers University president. “We are thrilled to work with IOOS to enhance this understanding at such a critical time for our planet.”

IOOS is a federal, regional and private-sector partnership working to enhance the ability to collect, deliver, and use ocean information. IOOS delivers the data and information needed to increase understanding of oceans and coasts, so that decision-makers can act to improve safety, enhance the economy, and protect the environment. NOAA’s mission is to understand and predict changes in the Earth's environment, from the depths of the ocean to the surface of the sun, and to conserve and manage the nation’s coastal and marine resources.