Protecting Piping Plovers: How Conservationists Shield These Shorebirds From a Trio of Extinction Threats

It is a remarkable sight: a fluffy, sand-colored piping plover chick scurries across a beach, its long legs out of proportion to its round body. A nearby parent gives a two-tone piping whistle, which gives this species its common name.

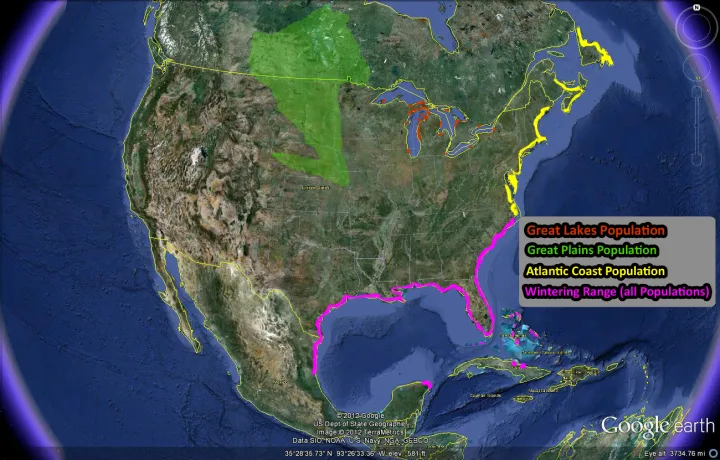

Birdwatchers and casual beachgoers are captivated by these birds, which can be spotted in parts of the Great Lakes region, the Northern Atlantic coast, and the Northern Great Plains. But part of what makes a piping plover (Charadrius melodus) viewing so special is its rarity — this species is facing the prospect of extinction.

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the piping plover is listed as “threatened” in the Northeast region with 2,289 breeding pairs in 2021. And the situation is even more dire in the population that inhabits the Great Lakes region, where there are only around 70-80 breeding pairs in an area that historically sustained 500-800 pairs.

These low numbers are the result of a combination of threats — including predators, human-caused disturbance and development, and climate change. Regulations such as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, and more recent critical habitat designations are credited for their continued existence today. But the situation still looks troubling.

“Shorebirds are really declining substantially. They’re one of the most at-risk guilds of birds in North America and in the Western Hemisphere,” said Dr. Allie Anderson who works with the Shorebird Science and Conservation Collective at the Smithsonian National Zoo’s Migratory Bird Center. “So it’s really, really alarming.”

There are several features of piping plovers that put them especially at risk compared to some other shorebirds. First, they are rather picky about where they will lay their eggs, nesting only on small sections of shorelines in the Great Lakes, Great Plains, and the Atlantic coast. This specific habitat need is a limitation for them because any change to the availability of this space will have a direct impact on their population size. In addition, according to the migration data that research and monitoring teams have collected and contributed to the Shorebird Science and Conservation Collective, piping plovers migrate from these northern beaches to the Gulf of Mexico, Atlantic coast, and Caribbean every winter, which exposes them to a wide range of areas and conditions that can present a variety of risks.

One of these risks is predators, which has become an emergency for piping plovers, according to Dr. Francesca Cuthbert, a piping plover expert and professor at the University of Minnesota. Predation has increased in recent years due to increases in predator populations and increases in number of adult plovers and their young. “It’s a crisis. It’s happening to eggs and to chicks and to adults, and there are a lot of predators out there,” Cuthbert said. She includes merlins, crows, ravens, gulls, and coyotes in the list.

To protect these rare birds from predation, Dr. Cuthbert works with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture-Wildlife Services, and other members of the Great Lakes Piping Plover Research and Recovery Effort, keeping the birds and their predators out of direct contact. With government permission, the conservationists can capture and relocate the predators, putting them out of the area of the plovers. Usually, they set up cages (called “exclosures”) over the nests so that raptors and mammals can’t access piping plover eggs. And in situations where the nests have no chance of surviving in the wild, the conservationists transfer eggs to their captive rearing program where they are incubated and chicks are raised and cared for by staff from U.S. zoos before being released back into the wild in a safe location.

Aside from predation, piping plovers are also threatened by human actions. Since piping plovers like sandy beaches, which are also popular among human beach-lovers, piping plovers and humans often come into close contact. Humans can leave food that attracts predators, allow their dogs to run off-leash, build houses on an otherwise suitable nesting habitat, or cause unnecessary stress for the birds during the breeding season.

Humans can also take steps to counteract their negative effect. Volunteer monitors hike shorelines looking out for plovers, and occasionally officials close beaches to ensure piping plover safety, as on parts of Cape Cod. Moreover, some of the shoreline piping plovers use has been federally designated as critical habitat, protecting these areas from further disruption.

But a third major risk facing piping plovers — and one that may be hardest to control — is the effect of rising water temperature and water levels due to climate change. Piping plovers are particularly sensitive to water levels since they build their nests on firm, sandy strips of beach near the water. When water rises, there is less beach space between the water and vegetation, which limits the space piping plovers can use for nests. If water levels get too high during the breeding season, the water can wash out nests and then the breeding attempt is over.

While high water levels during the breeding season are an obvious threat, piping plovers also rely on some flooding and ice cover during the winter season to scour vegetation away and clear beaches for the following spring’s nesting. As water temperatures rise, there is less ice cover and fewer suitable nesting spots. This delicate balance of flooding makes slight changes to the environment a challenge for piping plovers. According to Dr. Cuthbert, “the disruption by climate change really affects the breeding season. It’s hard to know — what can they actually take and still survive and continue recovery as temperatures rise and habitat declines?”

Luckily, using tracking data shared with the Shorebird Science and Conservation Collective, predator prevention, and captive rearing, professional and volunteer conservationists are protecting these birds, other species, and their environment for the future. They have already seen an increase in the vulnerable Great Lakes population in recent years, despite these many challenges.

According to Anderson, this gives reason for hope. “When actions are taken to help these species, you can see changes. Even in the climate change world, that's true as well.”