Sylvia Earle’s Algae Epic

The Smithsonian is home to renowned collections of importance and beauty. One unassuming collection housed in the drawers of the botany department of the National Museum of Natural History may not appear particularly awe inspiring—it includes hundreds of sheets containing preserved seaweed. But for scientists studying algae and the ocean it is a priceless gift that catalogues the changes occurring in the marine world. It is also the life’s work of renowned biologist Sylvia Earle.

“As my worked progressed over the years, I realized the central headquarters for keeping the history of life intact is here at the Smithsonian Institution.”

Sylvia Earle is one of the great naturalists of the last century and is named among the likes of David Attenborough and Jane Goodall. She was the first woman to lead the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration as Chief Scientist, holds the record for the deepest untethered dive, and has led innumerable missions across the globe. Born in 1935, she continues to passionately advocate for ocean conservation.

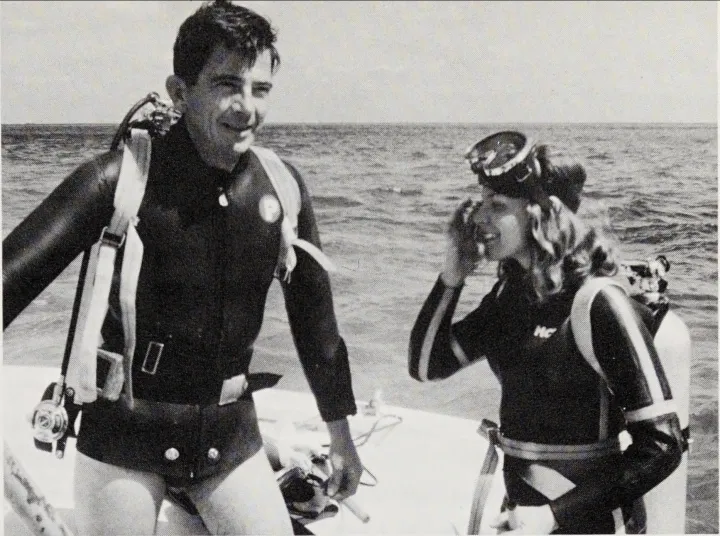

As a young scientist in the 1950s, Earle wet her feet on the shore of the Gulf Coast. As an undergraduate at Florida State University, an introduction to marine biology course by mentor Harold Humm had her hooked. Humm’s course exposed his students to field work, which included the study of marine seaweeds. The course also exposed Earle to a brand-new technology, scuba, and those formative experiences shaped her career’s trajectory. Very few scientists were using scuba gear, and as Earle narrowed her research focus on algae, she had a leg up on the generation before her.

“Unlike my predecessors who were exploring the Gulf of Mexico looking at seaweeds, I could actually get out to where they were growing. Like taking a walk in a forest, I could stroll through these underwater gardens. It was the first time, literally, that anyone was at the places that I was diving.”

Prior to the 1950s information about algae was learned through dredging using a drag or collecting dead algae that washed ashore. It is a make-do method of study that lacks context, including information about the type of environment where the algae grow. With scuba, Earle could witness and collect the algae right in its living habitat.

“It was transformative for me,” says Earle. “Before I could take a breath and stay down for half a minute, with scuba I could stay longer and go deeper.”

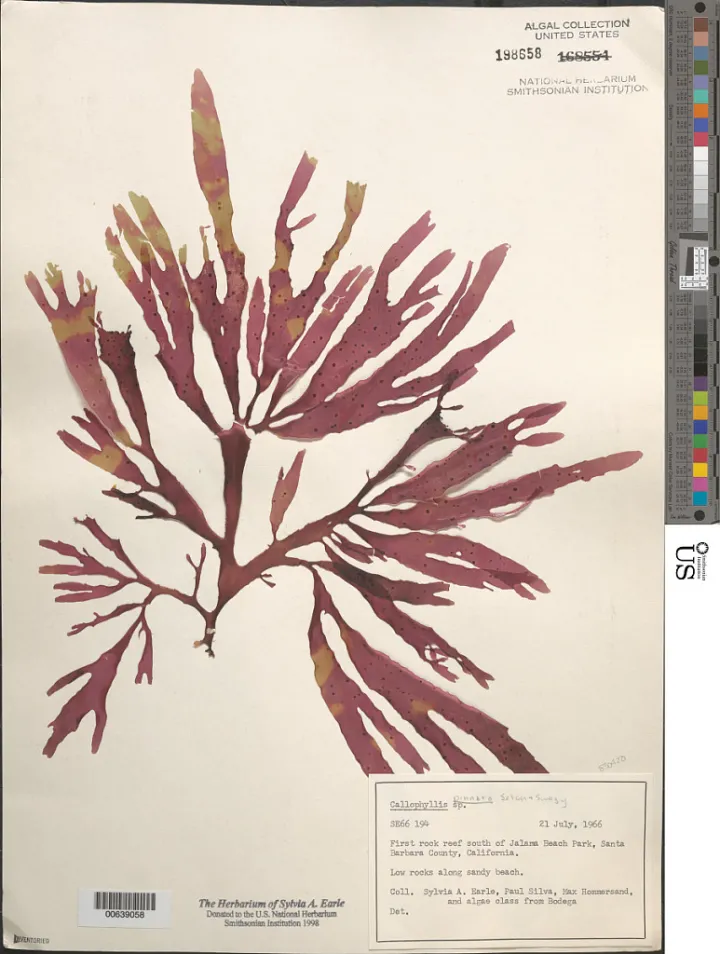

The completion of her doctoral thesis in 1966 was a landmark study and the most detailed first-hand catalogue of marine algae. Her study included observations of 20,000 aquatic plants. But that was only the beginning of a lifelong commitment to studying the ocean. Earle then continued to catalogue algae across the globe and became one of the most experienced deep-sea divers and a renowned algae expert who not only studied the marine world but advocated for its protection. With each expedition she dutifully set her collected specimens on sheets of paper using techniques learned from her mentor Humm in her introduction to marine biology course. From Chile, to Ecuador, California and Alaska, the algae in Earle’s collection tell the story of changing seas.

“I regard myself as a witness to change over time,” says Earle. “I experienced decades of change. Some of the changes are really good, and some of them are not so good. I have lived the better part of a century. The collections can be a source like silent witness to this change and they will persist far beyond my time.”

The algae collection, which is a part of an “herbarium” or botany library, is a living record of the world and can provide scientists with information about a seaweed’s geographical distribution, physical characteristics of the species, and how these attributes change over time. Recent technologies enable the study of a specimen’s DNA, its biochemistry, and can shed light on what types of animals fed on the specimens through the study of bite marks. DNA extraction would have seemed like science fiction sixty years ago when Earle began her collection, but since the physical specimen was preserved scientists can now study algae genetics from the past.

“You cannot extract DNA from a photograph,” says Earle. “Those (of us) have taken pains over the ages to take a reference piece of the environment and tuck it away so that at any time in the future with new insight (we can ask) new questions we don’t even know how to answer today.”

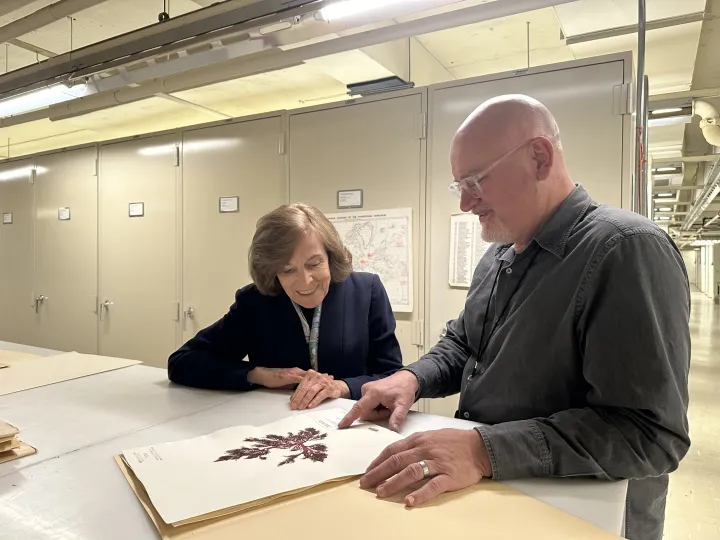

In 1999 Sylvia Earle donated her life’s work to the Smithsonian. The collection at the museum of natural history includes over 6,000 herbarium sheets with meticulously preserved algae and seagrass specimens from across the globe. Even more are housed at the museum’s offsite support center. Today, the sheets can provide critical information about the past world that they lived in. They are also digitized and can be viewed by anyone with access to the internet.

Upon returning to her collections at the Smithsonian in the late fall of 2024, Earle fondly reminisced about the expeditions and places where she collected each specimen. At the age of 89 she still eagerly talks about her upcoming diving plans, and her passion for the ocean and its seaweeds is still infectious decades after her first time diving. When asked what her favorite algae in the collection is, Earle’s answer was simple.

“My favorite ones are the living ones.”